Archive for the ‘social movements’ Category

party in the street: reason magazine

Reason magazine was gracious to feature Party in the Street in its December issue. A few clips from an extensive review of the book:

Party in the Street is a deceptively cheery title for an autopsy. In this book, the social scientists Michael T. Heaney and Fabio Rojas dissect the remnants of “the second most significant antiwar movement in American history” after Vietnam—the post-9/11 effort to restrain the American war machine.

In the years after the September 11 attacks, Heaney and Rojas write, peace activism became “truly a mass movement”: From 2001 through 2006, there were at least six anti-war demonstrations that drew more than 100,000 protestors, “including the largest internationally coordinated protest in all of human history” in February 2003.

The authors brought teams of researchers to most of the largest national protests from 2004 to 2010, and gathered reams of survey data from more than 10,000 respondents. Early on, they noticed substantial overlap between anti-war agitation and affiliation with the Democratic Party. That “party-movement synergy” helped the war opposition to expand dramatically during the administration of George W. Bush. It also, eventually, contained the cause of its undoing under Barack Obama. “Once the fuel of partisanship was in short supply,” Heaney and Rojas note, “it was difficult for the antiwar movement to sustain itself on a mass level.”

And:

What lessons can be learned from the collapse of the post-9/11 anti-war movement? Party in the Street‘s final chapter offers some “strategies for social movements” at a time of heightened partisanship. They won’t do much to cheer would-be reformers of any stripe. “In an era of partisan polarization, social movements risk experiencing severe fluctuations in support concomitant with variations in partisan success,” Heaney and Rojas write.

It’s a risk that seems nearly unavoidable. Resisting party loyalty is no guarantee that a movement will achieve its goals. The Occupy Wall Street movement of 2011 was so wary of being co-opted by political parties that Occupiers repulsed MoveOn’s attempts at solidarity and shouted down Green Party candidate Jill Stein at one encampment. Yet “antipartisanship had the effect of drastically narrowing Occupy’s supportive coalition,” the authors note.

Check it out.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

December 10, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in books, fabio, political science, social movements, uncategorized

informing activists – hosted by jennifer earl and thomas elliot

Mobilizing Ideas, the social movement blog, is hosting a series called “Informing Activists.” In this series, hosted by Arizona’s Jennifer Earl and Thomas Elliot, social movement scholar present their ideas to young activists. Check it out!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

December 4, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements, uncategorized

understanding how protest works: mizzou edition

There is a lot of writing on the resignations at Mizzou. Much has to do with race, others with college sports. In this post, I want to briefly touch on what social movement theory has to say about the effectiveness of the Concerned Student 1950 protest, which culminated when the Mizzou football team boycotted their game.

- Leverage: A lot of college protest is ineffective because it does not impose any real costs on administrators. For example, there were many Occupy Wall Street camps at colleges a few years back. My opinion is that the movement did not succeed for a number of reasons, one being that OWS did not actually force any real costs on their target. In contrast, strategically chosen boycotts can be highly effective. It has been reported that Mizzou gives up about a million dollars per forfeited game.

- Broad social support: The protest was the not the strategy of a single person, but of a wide range of people on campus. For example, the football players were able to recruit both black and white players. That does a lot to undermine the target of protest.

- Authority erosion: College protest often works when student activists successfully erode the authority of the leadership by challenging their ability to have others recognize their authority. While many made fun of the safe space at Mizzou’s campus, it is an effective disruption of the leadership’s ability to direct others on campus.

Bottom line: There is a lot to be learned about the mechanics of protest from the Mizzou boycott. Social movement scholars should use college protest as an opportunity to study how movements succeed and fail.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

November 12, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, higher education, social movements

party in the street: hypocrisy or not?

One of the responses to Party in the Street is that, in some way, we refuse to acknowledge the hypocrisy of activists. For example, Robin Hanson made the following observation on his blog, Overcoming Bias:

If they had framed their story more in terms of hypocrisy, they might have asked which media or interest groups tried to tell antiwar protesters the truth before Obama was elected, what reception they received, and why did other big media chose not to tell.

- I believe X is bad and I support people who do X.

- I believe X is bad but I think that my favorite person is better at dealing with X than the other guy.

#1 might be called “bad faith hypocrisy.” We know that our moral claims and actions are different. #2 is more subtle. One might call #2 hypocrisy, but that is misleading since hypocrisy seems to entail conscious contradiction of actions and moral claims. Instead, #2 might be called “misplaced trust.”

What evidence do we have that the antiwar movement declined due to misplaced trust than bad faith hypocrisy? To show that there is misplaced trust, all one needs to show is that activists supported their friend because of a plausible case that there were substantial differences that were acceptable in the moral frameworks of the peace activists. We review this evidence in detail (see chapter 2), but I’d suggest that the de-escalation of Iraq (negotiated under Bush, carried out under Obama) is the major piece of evidence that Obama did something that was consistent with their views. Perhaps the most important piece of evidence against my claim is the massive escalation of Afghanistan, but the Democratic position was always that this was good and the beef of many activists was with Iraq, not Afghanistan. i suspect that most activists simply think that a Democrat would do better and leave it at that.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

November 4, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in activism, books, fabio, political science, social movements

party in the street: podcast by caleb brown of the cato institute

My good friend and co-author Michael T. Heaney discussed Party in the Street with Caleb Brown of the Cato Institute. Nice summary of the major themes of the book.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

September 21, 2015 at 3:06 pm

Posted in books, fabio, political science, social movements

is black lives matter a social movement?

People often ask if a political group is a “movement.” In what sense is Occupy Wall Street or Black Lives Matter a movement? In the social sciences, protest movements are often defined by the following:

- A collective action (not a single person, or a group of people acting at once by coincidence)

- Aimed at structural change in society

- Using contentious or non-institutionalized means.

Then, yes, Occupy and Black Lives Matter (and the Tea Party and many others) are clearly protest movements. BLM is, I think, mainly defined by a desire to see a complete overhaul of how police interact with Black communities. And not in a reformist way either. They are willing to be disruptive.

Some people balk at this answer because they have other movements in mind, like the Civil Rights movement. The issue, I think, is that BLM is a very young movement that has not developed the infrastructure of other movements. The CRM took decades to evolve from the early days of the Niagra movement of 1905 to its height in the 1960s. Occupy and the Tea Party are atypical in that they popped up relatively quickly. Normally, movements take years to get off the ground. It is fair, then to say that BLM is a young movement, or an early stage movement, but it is definitely not a mature movement analogous to CRM in the 1960s. Bottom line: BLM is real, but it has a long way to go. Let’s see where it goes.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

September 2, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements

activism forum at mobilizing ideas

Mobilizing Ideas has a great forum on what activism means today. Some posts:

- Meghan Kallman, Brown University (essay)

- Rebecca Tarlau, Stanford University (essay)

- Alex Barnard, University of California-Berkeley (essay)

- Jaime Kucinskas, Hamilton College (essay)

- Kyle Dodson, University of California-Merced (essay)

- Erin Evans, University of California-Irvine (essay)

- Paul-Brian McInerney, University of Illinois-Chicago (essay)

- Ed Walker, University of California-Los Angeles (essay)

These are great folks. You can read previous posts about Paul-Brian McInerney, Ed Walker, and Jaime Kucinskas.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

August 14, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in activism, fabio, social movements

the uber-ization of activism

In the NY Times, UCLA sociologist and orgtheorist emeritus Ed Walker had an insightful column about the nature of modern activism. What does it mean when an interest group can just “rent” a bunch of people for a protest? From the column:

Many tech firms now recognize the organizing power of their user networks, and are weaponizing their apps to achieve political ends. Lyft embedded tools on its site to mobilize users in support of less restrictive regulations. Airbnb provided funding for the “Fair to Share” campaign in the Bay Area, which lobbies to allow short-term housing rentals, and is currently hiring “community organizers” to amplify the voices of home-sharing supporters. Amazon’s “Readers United” was an effort to gain customer backing during its acrimonious dispute with the publisher Hachette. Emails from eBay prodded users to fight online sales-tax legislation.

So it’s reasonable to ask whether there’s still a bright line between being a business and being a campaign organization, or between consumer and activist. Tech companies’ customers may think they are being served. But they are often the ones providing the service.

The whole column is required reading and illustrates the nebulous boundary between traditional politics and social movement politics. Self-recommending!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

PS. “Uberi-zation” is such a weird word…

Written by fabiorojas

August 12, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in activism, fabio, guest bloggers, political science, social movements

party in the streeet: response to econlog commenters

Last week, Bryan Caplan wrote two lengthy posts about Party in the Street (here and here). He focuses on a few issues: the differences between Republican and Democratic administrations on war policy and the exaggeration of differences by activists. Bryan also argues that the arguments typically made by peace activists aren’t those he would make. Rather than condemn specific politicians or make blanket statements about war, he focuses on the death of innocents and war’s unpredictability (e.g., it is hard to judge if wars work ex ante).

The commenters raised a number of questions and issues. Here are a few:

- Jacob Geller asks whether the collapse of the peace movement is spurious and could be attributed to other factors (e.g., the economy). Answer: There are multiple ways to assess this claim – the movement began its slide pre-recession (true), partisans are more likely to disappear than non-partisans during the recession (true), and the movement did not revive post-recession (true – e.g., few democrats have protested Obama’s war policies). Movements rise and fall for many reasons, but in this case, partisanship is almost certainly a factor.

- Michael suggested that there was a Democratic war policy difference in that Al Gore would not have fought Iraq. One can’t establish anything with certainty using counter factual history, but Frank Harvey suggested that President Gore would like have fought Iraq, given the long standing enmity and low level armed conflict between Iraq and the Clinton administration (including Gore).

- Also, a few people raised the issue of voting and if the antiwar issue was salient for Democrats. A few comments – one is that in data about activists, Democrats tended to view Obama’s management of war in better terms than non-partisans. Another point is that opinions on the war affected vote choice in multiple elections. The issue, though, isn’t whether Democrats were motivated by their attitudes on the Iraq War. The issue is how that is linked to movement participation and how that changes over time, given electoral events. All evidence suggests that the democratic party and the antiwar movement dissociated over time, leading to the peace movement’s collapse.

Thanks for the comments!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

July 22, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in books, fabio, political science, research, social movements

the emergence of gay rights: a sociological perspective

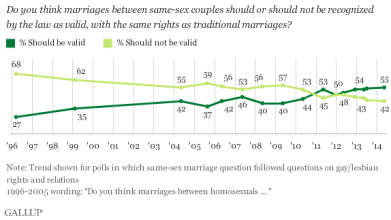

On Friday, the Supreme Court rules that marriage should be available straight and gay couples in all 50 states. This represents the most important policy victory so far of the gay rights movement. How did it get there? Future scholars will no doubt write extensively on this issue, but it helps to start with political science 101: social change starts with the median voter. Courts, in general, do not create rights. Rather, courts tend to codify and formalize the political rights that people are already willing to accept.

The graph is taken from an article in the Gallup web site and it drives home this point about public opinion. Somewhere around 2011, the public tipped in favor of gay rights. Not surprisingly, courts and states became more likely to support gay rights after this point. The question is, why did public opinion tip? When I think about this question, I often start with the “repetition hypothesis” – repeat your point enough and your previously weird idea will become normal (i.e., you shift from non-doxa to doxa, for you Bourdieu nuts). Dorf and Tarrow discuss how gay rights groups thought about this process in this Law and Social Inquiry article. Basically, they anticipated conservative push back to their views on gay marriage and crafted their appeals with that in mind.

Bottom line: Lawyers and Supreme Courts are the end game. The battle is won and lost in the arena of public opinion.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

June 29, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements

activist state – a documentary on the 1968 third world strike

You can also get my view in this article or chapter three of my Black Studies book.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

June 14, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in documentaries, fabio, social movements

cracked magazine discusses how the media makes people hate protestors

Cracked is one of the best mainstream media sources for good social science analysis (no joke). From their article about why people hate protestors:

Wait For One Of Them To Break The Law, Then Talk Only About That…

This might literally be the oldest trick in the book. I’m thinking powerful people have been doing this to protesters and activists since the days when getting gored by a mammoth was a leading cause of death. It plays out like this:

A) A certain group has a complaint — they’re being discriminated against, had their benefits cut, whatever — but they are not the majority.

B) Because the majority is not affected, they are largely ignorant and uninterested in what is going on with the complainers. The news media does not cover their issue, because it’s bad for ratings.

C) To get the majority’s attention, the group with the complaint will gather in large numbers to chant and block traffic, etc. This forces the media to cover the demonstration (since huge, loud groups of people make for good photos and video) and cover the issue in the process (since part of covering the protest involves explaining what is being protested). In America we’ve seen this tactic used by everyone from impoverished war veterans, to women seeking the right to vote, to the protests about police violence you’re seeing all over the news right now.

D) To counter this, all you need to do is simply wait for a member of the activist group — any member — to commit a crime. Then the media will focus on the crime, because riots and broken glass make for even more exciting photos and videos than the demonstrations. The majority — who fears crime and instability above all else — will then hopefully associate the movement with violence from then on.

And

Convince The Powerful Majority That They’re The Oppressed Ones… Last year a billionaire investor said criticism of the rich today is equivalent to the persecution of the Jews during the Holocaust. He’s not having a stroke; he’s under the influence of one of the most powerful techniques the system has in its arsenal. To get the majority to ignore complaints by any disadvantaged group, you simply insist that disadvantaged group has the real power and that the powerful majority is thus the underdog.

Mobilization should ask for reprint rights.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

June 10, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements, sociology, the man

protest matters, but it’s complicated

Over at Aeon Magazine, I have a short article on the question of whether protest works. Discussion of Gamson ’75 and more. A short clip:

Protest seems to be most effective when it is coupled with two things. First, there often needs to be an organized side of the movement. Movements succeed when some leader, or organization, appears who can help rally support, collect money, and make connections with insiders. While protest may jump start the process of social change, it still needs to be directed through institutions such as legislatures, courts, the educational system, and the for-profit sector. Outsiders need insiders, leadership makes the connection. Second, movements that succeed often have clearly stated goals that are consistent with our broader culture. There is a reason for the Civil Rights Movement’s success. The Civil Rights leadership worked tirelessly to connect Black equality with our Constitution and the desire to be a nation of free people. Thus, protest matters, but it has to work with other strategies and be suited to the problem.

Check it out.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

May 26, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements

book review: fighting for peace by lisa leitz

The recent Political Science Quarterly carries my book review of Lisa Leitz’ Fighting for Peace: Fighting for Peace: Veterans and Military Families in the Anti-Iraq War Movement. My choice quote:

As a study of social psychology, Fighting for Peace is a strong contribution to the ever-growing literature on activist identity and biography. It is a fitting addition to the scholarly work stemming from James M. Jasper’s The Art of Moral Protest, which explains how life events can lead people into activism. But there is a broader, more subtle lesson that can be drawn from this study. Many of the veterans and military family members joined protest movements because they felt that the deployment of the U.S. armed forces violated an important but unwritten contract between the civilian world and the military. Specifically, many veterans and family members resented the extremely long terms of deployment. Typically, American soldiers might expect one or two tours of duty in a theater of war. However, this policy changed during the Iraq war, as soldiers were routinely required to serve three or four tours of duty or were called back to duty after leaving the armed services. Thus, the movement among veterans and military families was not merely a protest against war, or even a specific war. It was also a protest against a broken promise between those who had volunteered to defend their country and those who had the power to send them into harm’s way.

Buy the book.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

Written by fabiorojas

May 13, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in books, fabio, social movements, veterans

social movements conference at notre dame

If you are in the Chicago/Michigan/Northern Indiana area, then you should probably go to this weekend’s social movement conference at Notre Dame. Friday will be sessions by young scholars and Saturday will be a lecture by Sidney Tarrow, who will receive a lifetime achievement award. Check it out!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

April 30, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements, sociology

conference on the humanities and diffusion

I got the following announcement from Arizona State about a conference on humanities and movements, diffusion, and culture – “Transforming Contagion.” Interesting stuff for those interested in cultural studies, history, and American studies. Here’s the link and a clip from the announcement:

Call for Papers

Symposium: “Transforming Contagion”

Location: Arizona State University’s West campus (Phoenix, AZ)

Date: Friday, October 23, 2015

We invite proposals for an exciting and provocative symposium on the topic of Transforming Contagion. This transdisciplinary and transhistorical symposium aims to explore contagion in its broadest sense by including perspectives about the spread, transmission, and modalities of contagion, and how contagion has been variously defined, imagined, and subjected to regulation and/or exploitation. By “contagion,” we do not necessarily mean only that which occurs in the body or within the framework of embodiment, but also contagions rooted in the literary, psychological, moral, educational, or political. We thus invite papers from any historical period or methodological approach that consider the complicated topic of contagion. Further, we invite papers that postulate how contagion itself might be transformed, deployed as a model for propagating revolutionary ideas, feelings, and beliefs, or utilized as a lens through which we can understand and critique our social and material world. We particularly invite papers that are radical, creative, feminist, boundary-smashing, intersectional, politically relevant, and wildly interdisciplinary.

Check it out.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

April 16, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in academia, conferences, fabio, humanities, social movements

let the conversation begin!

Hi everyone! Thanks to Katherine for inviting me back to blog a bit on Do-It-Yourself Democracy, Democratizing Inequalities, and other projects on my plate. I promise I won’t bring up federal agency mascots this time.

A little bit about me:

My #sociologicaldesk is currently covered in okra and tomato seedlings but my couch has books on it. My research interests lie at the intersection of movements, business, and democracy in American political development– otherwise known as “how did we get here?” For the purposes of orgtheory folks, I’m interested in politics and culture in organizations, especially the folks left holding the bag when organizational ideals meet everyday realities.

In Do-It-Yourself Democracy, I study the growing field of public engagement consultants. This book and my edited volume with Edward Walker and Michael McQuarrie focus on the causes and consequences of the dramatic expansion of participation in organizations during a time of increasing inequality. My new project focuses on civic engagement initiatives in higher education. Side interests include the use of art in organizations and movements. Sometimes these interests all come together.

As someone who studies the “new public participation,” I’d be remiss if I didn’t ask readers at the start what intrigues you about the forms participation takes today, whether in electoral campaigning, workplaces, health care, houses of worship, or community groups? What memorable experiences have you had in engagement facilitated from the top down, whether inside or outside of higher education, online or off? “Join the discussion!” and “Have your say!” below. Or, as Hillary said a campaign ago, “Let the conversation begin!“

Written by carolinewlee

April 12, 2015 at 4:34 pm

Posted in academia, inequality, social movements

Tagged with Edward Walker, organizations, public participation

big data and social movements

Mobilizing Ideas has a month long discussion about dig data and movement research. From Part I:

- Benjamin Lind

- Laura Nelson

- Austin-Choy Fitzpatrick

- Zachary C. Steinert Threlkeld

- Alex “The Roller” Hanna

- Thomas Elliot

Part II:

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

April 8, 2015 at 12:11 am

Posted in big data, fabio, social movements

Tagged with activism

Call for papers: Social movements and the economy

This is not an April Fool’s joke.

Call for Papers: Social Movements and the Economy

Northwestern University, Kellogg School of Management

Date: October 23-25, 2015We invite submissions for a workshop on the intersection of social movements and the economy, to be held at Northwestern University’s Kellogg School of Management from Friday October 23 to Sunday October 25, 2015.

In recent years, we have seen the rise of a vibrant literature engaging with questions of how social movements challenge firms, support the rise of new industries, and engender field change in a variety of domains of economic activity. A growing amount of attention has also been devoted to the ways that actors with vested interests in particular types of economic activity may resist, co-opt, imitate, or partner with activist groups challenging their practices. On the whole, there is now substantial evidence of a variety of ways that social movements effectively influence the economy.

And yet there has been less recent attention paid to the inverse relationship: classic questions related to how economic forces – and the broader dynamics of capitalism – shape social movements. This is all the more remarkable given the major economic shifts that have taken place in the U.S. and abroad over the past decade, including economic crises, disruptions associated with financialization and changing corporate supply chains, the struggles of organized labor, and transformations linked to new technologies. These changes have major implications for both the theory and practice of social movement funding, claims-making, strategic decision-making, and the very targeting of states, firms, and other institutions for change.

This workshop seeks to bring together these two questions in order to engage in a thorough reconsideration of both the economic sources and the economic outcomes of social movements, with careful attention to how states intermediate each of these processes.

The keynote speaker will be John McCarthy, Distinguished Professor of Sociology at Pennsylvania State University.

The workshop is planned to start with a dinner in the evening on Friday 10/23, to conclude with morning sessions on Sunday 10/25. Invited guests will be provided with domestic travel and accommodation support.

Submissions (PDF or DOC) should include:

– A cover sheet with title, name and affiliation, and email addresses for all authors

– An abstract of 200-300 words that describes the motivation, research questions, methods, and connection to the workshop theme

– Include the attachment in an email with the subject “Social Movements and the Economy”Please send abstracts to walker@soc.ucla.edu and b-king@kellogg.northwestern.edu by May 15, 2015. Notification of acceptance will occur on or around June 15.

Contact Brayden King (b-king@kellogg.northwestern.edu) or Edward Walker (walker@soc.ucla.edu) for more information.

Written by brayden king

April 1, 2015 at 9:14 pm

Posted in markets, political science, social movements

meet me in arkansas!!!!

I’ve been overwhelmed by snow, children, work, Mario Kart, exercise, and a whole bunch of other stuff. I’ll post new stuff in about a week or so. But, for now, I wanted to tell you about my upcoming talk at the University of Central Arkansas. The Arkansas Center for Research in Economics is hosting a series of events relating to Black History month. This Thursday evening, I will give a talk on the topic of what modern activism can learn from the civil rights movement. Click here for details. Later this week, we’ll have another guest post by Raj Ghoshal and an announcement of two talks about Party in the Street. And, as usual, if you want the “mic” while I am on blogcation, send us a guest post.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

February 22, 2015 at 4:15 am

Posted in academia, fabio, shameless self-promotion?, social movements

party in the street: discussion at popular resistance

My friend and co-author Michael Heaney has a post about our work at Popular Resistance, a web site dedicated to contemporary activism. A key quote:

So what would genuine independence from a political party look like for a social movement? My view is that independence means choosing allies regardless of their partisan affiliation. An independent movement should have allies that are Democrats, Republicans, members of other political parties, and nonpartisans. Independence means educating activists that parties are neither the enemy nor the savior; rather, they are one more political structure that can be used for good or ill. An independent movement should embrace working with allies on one issue if there is agreement on one issue, even if there is disagreement on a multitude of other issues. Independent movements should advance the best arguments supporting their cause, regardless of whether these arguments are typically classified as conservative, liberal, socialist, or using some other label. They should socialize their supporters to learn about and care about their cause above achieving electoral victories. Elections are a potential means of achieving social and political change, but they are neither a necessary nor sufficient condition for doing so.

I concur. There needs to be a discussion within modern movements about learning to work cross-party and often independently from parties. Read the whole piece.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

February 16, 2015 at 4:58 am

Posted in books, fabio, political science, social movements

party in the street: show me the money!

At the Washington Post’s Monkey Cage blog, Andrew Gelman wrote a very gracious review of Party in the Street, but he had one criticism:

The only place it seemed weak–and this weakness occurs in many treatments of politics, including much of my own work–is in its glancing treatment of money in politics. It is perhaps no surprise that the Tea Party found ample funding from some rich people, given that one of its central goals is to keep down taxes on the rich. Raising funds for an antiwar or anti-corporate movement proved to be more of a challenge (in the words of Heaney and Rojas, “the antiwar movement had few financial resources and ran on a shoestring budget”). Meanwhile, the Democratic Party has needed to keep an eye on wealthy individuals and corporations (not just labor unions) to keep itself going. These financial imperatives formed much of the background to the individual choices that are detailed in this book.

Here are a few comments on money and social movement politics. First, unlike electoral politics, money is a bit harder to track in social movements because so many groups are informal and do not register as 501(c) groups. So there is no paper trail for us to work with, although a few groups have IRS forms you can examine. Second, compared to other types of political action, protest is relatively cheap. In my personal judgment, one only needs about one or two million dollars per year to run a nation wide movement of this sort. This is about what a single prominent lobbying group or political consulting firm might charge to a prominent client. It is also an amount that a single “angel” could donate if they really wanted to.

This leads me to believe that money is only a partial explanation for the movement’s decline. It is true that donors stopped giving to the antiwar movement, but that’s not the ultimate explanation. Protesting Obama certainly would turn off some well heeled donors, but the fact that there was not an angel, or a swell of grass roots fund raising for a relatively modest sum, indicates to me that the drop in support was wide spread and not just a function of a few party elites.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

February 11, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, power, shameless self-promotion?, social movements

party in the street: social identities and policy continuity

One of the issues that we draw attention to in Party in the Street is that there was a great deal of continuity in war policy between the Bush and Obama administrations. This is an example of a broader theme in American government: domestic disputes are not brought into foreign policy. The phrase for this is “politics ends at the water’s edge.”

The water’s edge idea has important implications for social movements, especially progressive movements that are often participating in anti-war activism. Normally, we think of movements responding to some sort of stark contrast in policy and they expect different political actors to have distinct views on policy. For example, it is pretty safe to say that Democrats and Republican leaders promote very different abortion policies.

In contrast, the “water’s edge” theory suggests that there will be a fair amount of continuity between administrations in terms of foreign policy. It doesn’t mean total similarity, but a great deal of overlap. For example, the Iraq withdrawal was initially negotiated by the Bush administration and then carried out by Obama’s administration. Similarly, both the Bush and Obama administrations, at various times, sought to extend US involvement in Iraq. Did both administrations have identical policy? Definitely not, but there is a lot of continuity and overlap.

If you believe that movements closely follow policy, then the overall path of the antiwar movement might seem puzzling. When Bush surged, the movement began its decline. As Obama sought extensions in Iraq, there was little protest. Antiwar activists did not focus on the main instrument of withdrawal, the Status of Forces Agreement, initiated by Bush. The War on Terror involved over 100,000 troops “on the ground” from 2003 till about 2010.

We argue in Party in the Street that the overall growth and decline of the antiwar movement can be better explained by the tension of activism and partisanship instead of policy shifts. Early on, the antiwar movement’s identity did not conflict with its ally, the Democratic Party. So the movement could draw partisans and grow during the early stages of the Iraq War. As elections changed the landscape, partisanship asserted itself and the movement ebbed. And that is how we get a declining movement as the US intervention in Iraq is sustained, then incrementally reduced during a multi-year withdrawal phase and the vastly expanded in Afghanistan.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

February 6, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in books, fabio, research, social movements, sociology

social movement research at espn!!

Nate Silver’s fivethirtyeight.com and ESPN have produced a film series called “The Collectors,” which features people who collect data. The second film is about Dana Fisher, a social movement scholar who conducts surveys of protestors. She is the author of two books on politics, Activism, Inc. and National Governance the Global Climate Change Regime. Recommended!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($1!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

January 15, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements

party in the street: the first podcast

New Books in Political Science has dedicated their first podcast of the year to Party in the Street:

Heaney and Rojas take on the interdisciplinary challenge at the heart of studies of interest groups and social movements, two related subjects that political scientists and sociologists have tended to examine separately from one another. What results is a needed effort to synthesize the two social science traditions and advance a common interest in studying how people come together to influence policy outcomes. The particular focus of this work is on how the antiwar movement that grew in the mid-2000s interacted with the Democratic Party. They ponder a paradox of activism that just as activists are most successful – in this case supporting a new Democrat controlled House and Senate in 2006 – the energy and dynamism of the movement often fades away. Heaney and Rojas look to the relationship between antiwar activists and the Democratic Party for answers. They find that in a highly polarized partisan environment, party affiliations come first and social movement affiliations second, thereby slowing the momentum movements generate in their ascendency.

Please click on the link for the podcast.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($1!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

January 12, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in blogs, books, fabio, political science, social movements, sociology

review of missing class by betsy leondar-wright

Managment INK, the blog about management research links to my recent book of review of Missing Class by Betsy Leondar-Wright. The book is about the cultural differences between working class, middle class and wealthy activists. Overall, I liked it. One thing that I would like to see if more of a focus on group outcomes, similar to Kathleen Blee’s work. Did the cultural differences make a difference in mobilizing? But aside from that point, it’s a good review of how mobilizing occurs in the North American left. Recommended.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($1!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

January 10, 2015 at 12:01 am

Posted in books, fabio, social movements, sociology

party in the street: the main idea

For the last eleven years, my friend Michael Heaney and I have conducted a longitudinal study of the American antiwar movement. Starting at the 2004 Republican National Convention protests in New York City, we have been interviewing activists, going to their meetings, and observing their direct actions in order to understand the genesis and evolution of social movements. We’ve produced a detailed account of our research in a new book called Party in the Street: The Antiwar Movement and the Democratic Party after 9/11. If the production process goes as planned, it should be available in February or early March.

In our book, we focused on how the antiwar movement is shaped by its larger political environment. The argument is that the fortunes of the Democratic party affect the antiwar movement’s mobilization. The peak of the movement occured when the Democratic party did not control either the White House or Congress. The movement demobilized as Democrats gained more control over the Federal government.

We argue that the the demobilization reflects two political identities that are sometimes in tension: the partisan and the activist. When partisan and activist goals converge, the movement grows as it draws in sympathetic partisans. If activism and partisanship demand different things, partisan identities might trump the goals of activist, leading to a decline of the movement. We track these shifting motivations and identities during the Bush and Obama administrations using data from over 10,000 surveys of street protestors, in depth interviews with activists, elected leaders, and rank and file demonstrators, content analysis of political speeches, legislative analysis, and ethnographic observations.

If you are interested in social movements, political parties and social change, please check it out. Over the next month and a half, I will write posts about the writing of the book and the arguments that are offered.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($1!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

Written by fabiorojas

January 6, 2015 at 12:01 am

response to seth masket on social protest and civil rights

Seth Masket recently discussed the popularity of Martin Luther King, Jr. and the civil rights movement more generally. In general, the civil rights movement was deeply unpopular, even at its height. Polls showed that a majority approved of civil rights after the fact.

The point is well taken, but there is more to the story of public opinion and civil rights. Roughly speaking, public opinion was moving the direction of civil rights for decades, even if the general public didn’t quite approve of individual people or groups. It didn’t happen by itself. As Taeku Lee shows in Mobilizing Public Opinion, public opinion started to soften because of activism. A lot of local action caused civil rights to emerge on the agenda of elites at the state and federal levels.

Seth is right that for most people, the time is never right for protest. But that is not necessary for movements. You can accomplish a lot with a strongly motivated coalition of activists and elites. And if you push hard enough, public opinion will follow.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz/From Black Power

Written by fabiorojas

December 17, 2014 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, political science, social movements

q&a with hahrie han: part deux

We continue our Q&A with Hahrie Han on her new Oxford University Press book, How Organizations Develop Activists.

Question 3. A crucial distinction in your book is mobilizing vs. organizing? What does that mean?

The highest engagement organizations in my study combined what I call “transformational organizing” with “transactional mobilizing.” The difference between mobilizing and organizing really comes down to the extent to which organizations invest in developing people’s skills, motivations, and such as they do the work. Mobilizers are focused more on breadth–getting more people to do more stuff–so they care only about the “transactional” outcomes: how many people wrote the letter? Organizers believe that they achieve breadth by building depth–how many people became more motivated or more skilled (“transformed”) as activists by being part of the letter writing campaign? So they design work that may be harder at first, but builds more depth over the long-term.

It might be easiest to describe the difference between “transformational organizing” and “transactional mobilizing” through some examples.

Let’s say an organization wants to generate a letter writing campaign to get letters to the editor published around a particular issue. Mobilizers would create letter templates and tools people could use to click a few buttons and send off a letter to their local paper. Organizers might ask people to compose their own letter, using trainings they provide. Or, organizers might match potential letter writers with a partner to compose a joint letter.

Mobilizers would have a few staff people organizing the entire campaign–those staff would create the templates, craft the messages asking people to write the letters, and coordinate any needed follow up. People themselves would not have to do anything more than click the buttons to indicate their willingness to write the letter. Organizers would set up the campaign so that staff people might design the trainings and the goals, but a distributed network of volunteers would be charged with generating letters in their local communities. Then, they would train and support those volunteers in getting those letters.

The organizations that had the highest levels of activism did both–they did organizing AND mobilizing to get both breadth and depth. It’s not that one is better than the other; it’s that organizations need both.

Written by fabiorojas

November 20, 2014 at 12:01 am

Posted in books, fabio, guest bloggers, political science, social movements, sociology

q&a with hahrie han: part 1

This week, we are having a Q&A with our recent guest blogger, Hahrie Han. She is a political scientist at Wellesley College and has a new book out on the topic of how organizations sustain the participation of their members called How Organizations Develop Activists. If you want, put any questions you may have in the comments.

How Organizations Develop Activists: Civic Associations and Leadership in the 21st Century

By Hahrie Han (@hahriehan)

Question 1. Can you summarize, for the readers of this blog, your new book’s main argument? How do you prove that?

The book begins by asking why some organizations are better than others at getting (and keeping) people involved in activism than others. All over the world, there are myriad organizations, campaigns, and movements trying to get people to do everything from signing petitions to showing up for meetings to participating in protest. Some are better than others. Why?

To answer this question, I wanted to look particularly at what the organization does. There are so many factors that affect an organization’s ability to engage activists that the organization itself cannot control. What about the things it can control? Do they matter? So I set up a study of two national organizations working in health and environmental politics that also had state and local chapters operating relatively autonomously. I created matched pairs of these local chapters that were working in the same kinds of communities, and attracted the same kinds of people to the organization. But, they differed in their ability to cultivate activism. By examining differences among organizations in each pair, I could see what the high-engagement organizations did differently. I also ran some field experiments to test the ideas that emerged.

I found that the core factor distinguishing the high-engagement organizations was the way they engaged people in activities that transformed their sense of individual and collective agency. Just like any other organization, these organizations wanted to get more people to do more stuff, but they did it in a way that cultivated their motivations, developed their skills, and built their capacity for further activism. Doing so meant that high-engagement organizations used distinct strategies for recruiting, engaging, and supporting volunteers, which I detail in the book. By combining this kind of transformational organizing with a hard-nosed focus on numbers, they were able to build the breadth and depth of activism they wanted.

Written by fabiorojas

November 18, 2014 at 12:01 am

Posted in books, fabio, guest bloggers, nonprofit, social movements, sociology, strategy

meet me in california!!!

This Friday, I will be a guest of the department of sociology at the University of Southern California. I’ll be giving a talk called “The Four Histories of Black Power: A Sociological Challenge to Black Power History” It’s about how social movement theory can be used to critique and re-articulate our understanding of Black Power. Come by and say hello!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz/From Black Power

Written by fabiorojas

October 23, 2014 at 12:16 am

Posted in fabio, self-promotion?, shameless self-promotion?, social movements

the meditation movement and the challenge to the theory of fields or, why you should check out jaime kucinskas’ work

Mobilizing Ideas recently ran a post about emerging stars of social movement research. I was thrilled to see three folks with IU connections – Matt Baggeta of IU’s top ranked policy school, Casey Oberlin of Grinnell (IU grad), Jaime Kucinskas of Hamilton (another IU grad). I’ve already discussed Casey’s work on this blog, so let me take a moment to tell you why you should pay attention to Jaime’s work.

Jaime’s dissertation was a study of religious change. Specifically, the rise of meditation as a serious topic in academia and American popular culture. Basically, meditation has found its way into many areas of American social life – even the military! The reason Jaime finds this interesting is that it is a serious change in American spiritual life that happened without the process of conflict and resource mobilization as described in works like Fligstein and McAdam’s Theory of Fields.

Jaime points out that movements can have great impacts by bypassing the contentious politics route. She argues that American meditation is a top down, elite driven movement that does a lot of institutional work behind the scenes and uses the levers of elite institutions to subtly inject new religious practice into popular culture. Based on great field work and extensive interviews, it is a great case study with broad and deep implications. Check it out.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz/From Black Power

Written by fabiorojas

October 8, 2014 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements, sociology

marijuana legalization as social movement

Vox ran an article asking how marijuana legalization came to have so much support. In speaking to German Lopez, I offered a tipping point theory and some thoughts about the low cost of information:

Rojas of Indiana University suggested the advancements of the movement could be a self-perpetuating cycle: As more states legalized medical marijuana, Americans saw that the risks of allowing medicinal use didn’t come to fruition as opponents warned. That reinforced support for medical marijuana, which then made politicians more comfortable with their own support for reform.

A similar cycle could be playing out with full legalization, Rojas explained. As voters see medical marijuana and legalization can happen without major hitches, they might be more likely to start supporting full legalization.

“People said, ‘Okay, now that someone else is throwing this out in public, it’s okay for me to vote for it or approve it,'” Rojas said. “That’s probably the main driving force: using the electoral system to push ideas that people may be afraid to think about or consider because they’re illegitimate — or at least they were.”

The rapid change in public opinion could have been helped along by the internet, which allows people to share stories about their own pot use, research about the issue, and states’ experiences with relaxed marijuana laws much more quickly.

“When I was a college student around 1990, other than hardcore political wonky types, … nobody really talk about drug legalization,” Rojas said. “Now, you can go on Facebook or Twitter or Instagram, and people can share a news story. You get exposed to it constantly.”

Check it out.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz/From Black Power

Written by fabiorojas

October 2, 2014 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, social movements

hong kong protest – initial questions

Right now, pro-democracy protesters are in conflict with police in Hong Kong. I am not a China expert, so my knowledge is limited. A few questions for readers who know more than I do:

- What lessons have the Chinese state and activists learned from previous rounds of pro-democracy protest?

- Is this “internally generated?” Or have activists received training and support from outside China?

- Was this triggered by specific events, or is this a response to the slow assertion of mainland power in Hong Kong?

Use the comments!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz/From Black Power

Written by fabiorojas

September 29, 2014 at 3:32 am

Posted in fabio, social movements

organizing, mobilizing, and the people’s climate march – a guest post by hahrie han

Hahrie Han (@hahriehan) is an associate professor of political science at Wellesley College. She is a leading expert on political organizations, activism, and civic engagement. Her first book is Moved to Action: Motivation, Participation, and Inequality in American Politics. Her new books discuss the Obama campaign organization and the cultivation of leadership. This guest post draws from her recent work.

++++

On Sunday, somewhere between 300,000 and 600,000 people gathered in New York City for the People’s Climate March—the largest march for climate justice in history and, as Bill McKibben pointed out in one of his tweets following the march, “the largest political gathering about anything in the US in a very very long time. About anything!” How were march organizers able to get so many people engaged in this moment of collective action?

The #PeoplesClimateMarch created a flurry of activity online—a number of different organizations reached out via social media, organizers created and distributed a short movie called “Disruption” to advertise the march, and organizations themselves reached their members via multiple online tools. Although some media has focused on this online activity to explain the success of the march, the real story lies behind the tweets and online posts.

In my recent book, How Organizations Develop Activists: Civic Associations and Leadership in the 21st Century, I asked what explains the difference between organizations that are really good at getting people involved in civic and political action around health and environmental issues and those that are not as good. I found that what differentiated the highest engagement organizations was their ability to blend mobilizing (transactional actions, including many online actions, designed to get as many people as possible to do something) with organizing (transformational work designed to transform people’s capacities for action). Many organizations confuse mobilizing and organizing, but I argue that they are quite different, and have many different implications for activism, democratic theory, and civic engagement (see here and here for a description of the difference between the two).

The highest engagement organizations in my study used mobilizing strategies to reach people at scale, and organizing strategies to develop the leaders they needed who could do that outreach. The math is simple: the more people there are mobilizing their own personal networks to take action, the more likely the organization is to achieve scale. How do you develop leaders who have the willingness and skills to mobilize their networks? Organizing. Distributing leadership through organizing, in other words, was their secret to mobilizing at scale, and achieving wins like what we saw with the People’s Climate March.

Consider Phil, for instance, an environmental organizer profiled in my book (note that all the names used here are pseudonyms). He was responsible for organizing a statewide conference with the goal of bringing several thousand people together around a campaign to pressure the state legislature. At first, he tried to do the work alone—but quickly realized there was no way he could generate the kind of attendance they wanted if he worked alone. So he recruited a group of volunteer leaders to be part of the steering committee of the conference. Each of those volunteers recruited their friends to head up committees and subcommittees. Each committee chair was responsible for recruiting people to be part of her team. In the end, there was a group of about 100 volunteers responsible for planning the conference. Phil’s job was not to mobilize several thousand people, but instead to support and coach the volunteer leaders who were doing the mobilizing. By using organizing to build a structure of distributed leadership, Phil was able to mobilize at scale.

Despite evidence demonstrating the power of community organizing, many organizations choose not to do it because it’s too hard. Unlike mobilizing, organizing can be extremely time-consuming and resource intensive. It is always easier to craft a well-target email to send to a wide network than it is to have an agitational conversation with a new volunteer. The thing that organizations making this choice miss, however, is the fact that mobilizing becomes easier if they organize. This is a lesson that climate justice organizers learned over the years and put to good use in planning the People’s Climate March.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz/From Black Power

Written by fabiorojas

September 24, 2014 at 12:01 am

Posted in fabio, leadership, political science, social movements