Archive for the ‘higher education’ Category

thriving in the academic commons + labors of love in the time of pandemic

This year, like the past several years, I have the honor of serving as a mentor to tenure-track CUNY faculty in the CUNY Faculty Fellowship Publication Program (FFPP). The FFPP is a writing and professional development program that helps tenure-track faculty at CUNY two-year and four-year colleges navigate the ins-and-outs of publishing and tenure at their teaching and research-intensive universities. As a mentor, I get to read and comment on works in progress, across the disciplines, facilitate group learning processes, and connect with other highly accomplished mentors across CUNY; these responsibilities enact a cooperative philosophy of individual and collective learning-all-the-time.

Since this year’s FFPP orientation was virtual due to the pandemic, FFPP program directors Matt Brim and Kelly Josephs asked me to put together and record a presentation about publishing as a social scientist. I was also asked to comment on publication productivity for scholars who are caregiving during a time of pandemic, state repression/failures, and uncertainty.*

I’m sharing the direct FFPP link to my recorded presentation here in case it might help other scholars outside of CUNY.**

Since the video is not close captioned, I’ve cut and pasted the full script below. While I have embedded screenshots below, here’s my powerpoint presentation if you would like to look at the images of recommended resources, like guides for publication, up close:

“Greetings, I am Katherine K. Chen; I’m an organizational researcher and sociologist at The City College of New York and the Graduate Center, CUNY. I’ve been asked by FFPP to talk about the writing and publication process from the perspective of a social scientist. I’ve also been asked to discuss handling multiple roles in the academic commons during a time of pandemic, austerity, and state repression/failure.

When I was finishing my PhD thesis in graduate school, I came across a book called Deep Survival; in this book, journalist Laurence Gonzales distilled conditions that were common among the accounts of those who had survived disasters, plane crashes, and being lost in remote areas. I think many of these principles are applicable to the academic commons in both conventional times and uncertain times such as these.

I speak as someone who has experiences with journal publishing like the following:

(1) An editor sat on a revision that I submitted in response to a R&R, a revise and resubmit. The editor sat on the revised manuscript for 7 months [correction: it may actually have been 9 months…] before saying he was rejecting it, without sending it out for review. I told other folks I had met at a mini-conference about this dispiriting decision; well, they let a famous researcher who was putting together a special issue around his concept about my paper. That’s how I got introduced to a literature that catapulted my article into a higher ranked, well-known interdisciplinary journal. This scholar also invited me to dialogue with his work for another journal.

(2) I had a journal manuscript that I was absolutely in love with writing, about the difficulties that consumers have with navigating social insurance markets. In Aug. 2013, I sent the manuscript to a special issue for a general journal – this got rejected fairly quickly, with a few helpful review comments. I revised this and sent it to a regional journal in Oct. 2013. This also got rejected in Nov. 2013, with reviews that made it clear at least one reviewer didn’t understand the manuscript. I spent a lot of time revising the manuscript with a new framing, based on a new literature, and submitted to an interdisciplinary journal in July 2016. This version of the manuscript received a R&R; I did a revision. This was followed by another R&R that had the warning of a “high risk” R&R. I did one final push, as this was a make-it-or-break-it moment. For several years, I had spent all of my New Year Eves working on revisions to this paper, and I was hoping to break this yearly ritual, as much as I enjoyed working on the paper. Leading up to this final round, I was doing a reading group with a graduate student on an entirely different topic of school choice, and I also just happened to take the time to read a colleague’s book about the market of wealth management. These seemingly ancillary activities helped me hone my own theoretical concept of bounded relationality, generating a published journal article in highly ranked and regarded journal, more-so than the ones I had originally submitted to.

With these experiences in mind about how long it can take to publish research, I have translated several of the lessons from the Deep Survival book that I mentioned to our specific situations, which is about surviving and hopefully at some point thriving during a long journey towards publication and dissemination.

Here are how these ideas apply to thriving in the academic commons:

- Think relationally. For survivors, the thought of loved ones, real or imagined, was what kept them going on seemingly hopeless treks, even when they were tempted to give up. For academics, thinking relationally means the following: (a) First, who’s your audience? Who are you writing for, and why is it important? (b) Second, who’s in your corner? Who can you turn to for honest feedback? Who can be your cheerleader and supporter? Who can you offer the same in return? Can you form a writing group? Can you find a writing partner? These groups can really keep you going, even when you haven’t heard from reviewers and editors or the reviewer feedback is not what you expect.

- Prepare for your journey by anticipating possibilities. Survivors are prepared with maps and supplies. For academics, this means a lot of reading of examples in your field and how-to guides like: Wendy Belcher’s Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks or William Germano’s From Dissertation to Book.

- Adapt to changing circumstances. In the Deep Survival book, people got into trouble when they acted the way that they thought things should be – that the descent down the mountain should be easy, that there wouldn’t be a storm rolling in. Survivors didn’t reject what they saw or experienced – they adjusted to their conditions. If they were tired, they slept. If they were cold, they didn’t keep wandering around until they got hypothermia; they made a shelter with a fire instead. For academics, this means: (a) If you get a rejection, mourn it for a moment, then keep moving and talking with colleagues, prospective journals, or book publishers. (b) If you keep getting the same advice about your writing, think about how you can use this advice to fix your writing. (c) If you find that your intended audience isn’t receptive to your work, is there a different audience that might welcome your work? Do you need to build up those audiences by organizing conferences or special events and making connections?

- Reflect on where you are by learning a different perspective – The Deep Survival book argues that hikers need to periodically turn around and observe where they were, from a different vantagepoint, so that if and when they need to make a return journey, they can recognize the landscape. This one is a harder one for academics – this is essentially an argument for slow scholarship, for revisiting ideas developed in younger years, to question assumptions and original interpretations, to master different literatures and see how these could fit. Since so many of us have spent years developing expertise in particular areas, it’s tempting to hunker down and take a very linear and narrow path. Adopting different perspectives, crossing subdisciplinary boundaries lines can be generative, help you fall in love again with what originally drew you to research.

Now, I’m going to turn to a slightly different but related topic. Besides working as a tenured faculty, I am also a caregiver for a younger learner – in my case, a 6-year-old daughter and her community of now online learners. What does this mean? I can’t speak as a tenure-track faculty writing during a pandemic; I can only extrapolate from what I am doing and what I worry that junior faculty are experiencing. Here’s my suggestions:

- First, Be kind to yourself.

- Second, Reach out to others for support. Most people and communities do want to be helpful when they can. If you’re not a caregiver yourself, think about how you can support and be inclusive to those who are – Victoria Law and China Martens’ book Don’t Leave Your Friends Behind is a good guide.

- Third, Partner up with others to write.

- Fourth, Use the classroom in synergistic ways – learn about topics and/or methods that you’re interested in and test ideas.

- Five, If you can, use your experience to inform your research and vice versa. I aligned my research interests with what I was experiencing as a parent, instructor, and mentor.

- Six, Take the longterm view – expend your energy interdependently where you think possible futures should head. Many scholars have sought to contribute to the academic commons, in the hope of bettering lives and circumstances for themselves and those around them, despite so many wrenching circumstances. Many of us are the descendants of those who escaped wars, famines, genocides, and slavery, for example, and many of us are here today precisely because of mutual aid and cooperation. Our daily presence and mentorship of upcoming generations are what makes multiple futures possible.

Thank you so much for listening. Take care, and welcome to the CUNY academic commons.”

For other inspiration about writing and publishing, check out other content on the FFPP visual orientation page (some content is embedded, for others, you’ll need to scroll down and click the screenshot images to go to a dropbox link):

- Bridgett Davis recounts her experience with how abandoning 400 pages of writing lead to two additional books, including a memoir that she is now converting into a screenplay for a film.

- William Carr shares how a professional newsletter article about teaching at CUNY lead to an invitation to write about active learning for a textbook, thereby disseminating practices to wider audiences.

- Duke University Press editor Ken Wissoker discusses about publishing dissertation work as books.

- A FFPP group discusses their experiences as “The Writing Group That Never Quit.”

*Incidentally, the pandemic has accelerated skill acquisition and a reliance upon invisible labor and personal resources under challenging conditions. For those of who are instructing virtually from home, we’ve had to learn how to become video content generators, video-makers, and video editors. Some of us must use equipment that we have purchased ourselves and “free” labor donated by others.

** For those of you trying to budget time (or considering asking someone to provide video content), this 8-minute-long video involved several hours of set-up work, including writing and practicing the presentation and fussing with zoom recording and screen sharing settings. I could only complete it because the construction drilling in my complex had finally ended for the day, and I had gotten unpaid technical support from my zoom-savvy 6-year-old assistant. Another uncompensated work assistant (spouse) had sourced, purchased, and set-up the camera and boom mic.

hidden externalities: when failed states prioritize business over education

Much has been discussed in the media about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; for example, to compensate for the absence of coordinated support, working mothers are carrying more caregiving responsibilities. However, the full range of externalities resulting from governmental and organizational decisions (or in the case of some governments, “non”-decisions which are decisions in practice) often are less visible during the pandemic. Some of these externalities – impacts on health and well-being, careers and earnings, educational attainment, etc. – won’t be apparent until much later. The most disadvantaged populations will likely bear the brunt of these; organizations charged with addressing equity issues, such as schools and universities, will grapple over how to respond to these in the years ahead.

In this blog post, I’ll discuss one under-discussed implication of what’s happening in NYC as an example, and how other organizations have had to adjust as a result. Mayor DeBlasio has discussed how NYC public schools will close if NYC’s positivity rate averages 3% over 7 days. At the same time, indoor dining, bars, and gyms have remained open, albeit in reduced capacity. People, especially parents and experts, including medical professionals, are questioning this prioritization of business establishments over schools across the US.

Since the start of the 2020 school year, NYC public schools has offered limited in-person instruction. A few informal conversations I’ve had with parents at NYC public schools revealed that they found the blended option an unviable one. Due to capacity and staffing issues, a public school’s blended learning schedules could vary over the weeks. For example, with a 1:2:2 schedule, a student has 1 day of in person school the first week, followed by 2 days in person the following week, then another 2 days in person the third week. Moreover, which days a student can attend in-person school may not be the same across the weeks. This might partially explain why only a quarter of families have elected these. Overall, both “options” of blended learning and online learning assume that families have flexibility and/or financial resources to pay for help.

What’s the cost of such arrangements? People have already acknowledged that parents, and in particular, mothers, bear the brunt of managing at-home schooling while working from home. But there is another hidden externality that several of my CUNY freshmen students who live with their families have shared with me. While their parents work to pay rent and other expenses, some undergraduates must support their younger siblings’ online learning. Other students are caregiving for relatives, such as a disabled parent, sometimes while recovering from illnesses themselves. Undergraduates must coordinate other household responsibilities in between managing their own online college classes and additional paid work. Without a physical university campus that they can go to for in-person classes (excluding labs and studio classes that are socially distanced) or as study spaces, students don’t have physical buffers that can insulate them against these unanticipated responsibilities and allow them to focus on their learning, interests, and connections.

Drawing on the financial resources available to them and shaping plans around “stabilizing gambits,” several elite universities and small liberal arts colleges have sustained quality education for their students with their in-person classes, frequent testing, and sharing of information among dorm-dwellers. But in the absence of any effective, coordinated federal response to the pandemic in the US, what can public university instructors do to ensure that their undergraduate students have a shot at quality learning experiences? So far, I’ve assigned newly published texts that guide readers through how to more critically analyze systems. I’ve turned to having students documenting their experiences, in the hopes of applying what they have learned to re-design systems that work for more diverse populations. I’ve tried to use synchronous classes as community-building sessions, coupled with feedback opportunities on how to channel our courses to meet their needs and interests. I’ve devoted parts of class sessions to explaining how to navigate the university, including how to select majors and classes and connect with instructors. I’ve connected research skills to interpreting the firehose of statistics and studies about pandemic, to help people ascertain risks so that they can make more informed decisions that protect themselves and their communities and educate others. I’ve attempted to shift expectations for what learning can look like in the absence of face-to-face contact. Since many of the relational dimensions that we took for granted in conventional face-to-face classes are now missing (i.e., visual cues, physical co-presence), I’ve encouraged people to be mutually supportive in other ways, like using the chat / comments function. In between grading and class prep, I’ve written letters of recommendation, usually on very short notice, so that CUNY students can tap needed emergency scholarships or pursue tenure-track jobs. In the meantime, our CUNY programs have tried to enhance outreach as households experience illness and job loss, with emergency funds and campus food pantries mapping where students reside and sending mobile vans to deliver groceries, in an effort to mitigate food insecurity.

Like other scholars, I’ve also revealed, in the virtual classroom, meetings, and conferences, how the gulf between work/family policies is an everyday, shared reality – something that should be acknowledged, rather than hidden away for performative reasons. Eagle-eyed viewers are likely to periodically spot my child sitting by my side in a zoom meeting, assisting me by taking class attendance, or even typing on documents in the background. My capacities to support undergraduate and graduate learning, as well as contribute to the academic commons by reviewing manuscripts and co-organizing academic conferences, have depended on my daughter attending her school in-person. Faculty and staff at her school have implemented herculean practices to make face-to-face learning happen, and families have followed agreements about reducing risks outside of school to maintain in-person learning. That said, given current policy decisions, it’s just a matter of time when I will join other working parents and my CUNY undergraduates making a daily, hour-by-hour complex calculus of what can be done when all-age learners are at home.

All of these adjustments and experimental practices are just baby steps circumnavigating collective issues. These liminal times can offer opportunities to rethink how we enact our supposed values in systems and institutions. For instance, do we allow certain organizations and unresponsive elected leaders to continue to transfer externalities to those who are least prepared to bear them? Do we charge individual organizations and dedicated members, with their disparate access to resources, to struggle with how to serve their populations’ needs? Or, do we more closely examine how can we redesign systems to recognize and support more persons?

“don’t be afraid to push big, bold projects” and “be brave and patient”: Dustin Avent-Holt and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey on producing Relational Inequality Theory (RIT)

Dustin Avent-Holt and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, who collaboratively published their book Relational Inequalities: An Organizational Approach (Oxford University Press), graciously agreed to do a joint email interview with orgtheory! Here, we discuss their book and the process leading up to the production of the book. Readers who are thinking of how to apply relational inequality theory (RIT), join and bridge scholarly conversations, and/or handle collaborative projects, please take note.

First, I asked Dustin and Don substantive questions about RIT. Here, both authors describe how they used their workplaces in higher education as laboratories for refining their theory. Also, Don channeled his disappointment with the limits of Chuck Tilly’s Durable Inequalities into fueling this endeavor.

1. Katherine. How did you apply the insight of relational inequality in your own lives? For example, both of you are at public universities – how does knowing relational inequality affect your ways of interacting with other people and institutions?

Dustin. I think for me one of the ways I see this is becoming faculty during the process of writing the book and being in a transitioning institution. I was hired out of grad school to Augusta University when it had just merged with the Medical College of Georgia. With this merger, Augusta University moved from being a teaching-focused college to a comprehensive research university that includes both graduate and undergraduate programs and a mission focused on research. Experiencing this transition made me think through the daily lives of organizations in a much less structural way as I saw people negotiating and renegotiating the meaning of the institution, the practices and policies, creating new ways of fulfilling institutional roles, etc. I guess in that way it highlighted the work of Tim Hallet on inhabited institutionalism. As university faculty and staff, we didn’t just copy a bunch of templates from the environment, people were translating them and challenging them in the organization. And we still are, 7 years later, and I suspect we will be for a very long time. Organizations at that moment became enactments rather than structures for me, something to be relationally negotiated not simply imported. Don and my endeavor then to understand inequality in this context actually began to make more sense. And in fact during our weekly conversations about the book, I do remember often relating stories to Don of what was going on, and this certainly shaped how I thought about the processes we were thinking through.

I don’t know if that is what you were after in your question, but it is for me this experience shaped how I have come to think about organizations, and became central to how we think about organizations in the book.

Don. No fair, actually apply a theory in our own lives? Seriously though, I became pretty frustrated with the black hole explanations of local inequalities as reflecting “structure” or “history”. These can be analytically useful, but simultaneously disempowering. Yes, some students come to the University with cultural capital that matches some professors, but this does not make them better students, just relationally advantaged in those types of student-teacher interactions. At the same time the University exploits revenue athletes for its purposes while excluding many others from full participation. The struggles of first gen students and faculty are produced by relational inequalities.

As a department chair I was keenly aware of the university dance of claims making around status and revenue and that this had to be actively negotiated if our department was going to be able to claim and sequester resources. This sounds and to some extent is harsh, since success might mean taking resources indirectly from weaker or less strategic departments, although it can also feel insurgent if the resource appears to be granted or extracted from the Provost. But the truth is that university resources flow in a complex network of relationships among units, students, legislators and vendors (beware the new administrative software contract!).

The Dean will pretend this is about your unit’s “productivity”, it’s never that simple.* It’s also great to have allies, at UMass we have a great faculty union that works to level the playing field between departments and disrupt the administrative inequality dance.

* Katherine’s addition: Check out this satirical twitter feed about higher ed administration for laugh/cries.

book spotlight: beyond technonationalism by kathryn ibata-arens

At SASE 2019 in the New School, NYC, I served as a critic on an author-meets-critic session for Vincent de Paul Professor of Political Science Kathryn Ibata-Arens‘s latest book, Beyond Technonationalism: Biomedical Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Asia.

Here, I’ll share my critic’s comments in the hopes that you will consider reading or assigning this book and perhaps bringing the author, an organizations researcher and Asia studies specialist at DePaul, in for an invigorating talk!

“Ibata-Arens’s book demonstrates impressive mastery in its coverage of how 4 countries address a pressing policy question that concerns all nation-states, especially those with shifting markets and labor pools. With its 4 cases (Japan, China, India, and Singapore), Beyond Technonationalism: Biomedical Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Asia covers impressive scope in explicating the organizational dimensions and national governmental policies that promote – or inhibit – innovations and entrepreneurship in markets.

The book deftly compares cases with rich contextual details about nation-states’ polices and examples of ventures that have thrived under these policies. Throughout, the book offers cautionary stories details how innovation policies may be undercut by concurrent forces. Corruption, in particular, can suppress innovation. Espionage also makes an appearance, with China copying’s Japan’s JR rail-line specs, but according to an anonymous Japanese official source, is considered in ill taste to openly mention in polite company. Openness to immigration and migration policies also impact national capacity to build tacit knowledge needed for entrepreneurial ventures. Finally, as many of us in the academy are intimately familiar, demonstrating bureaucratic accountability can consume time and resources otherwise spent on productive research activities.

As always, with projects of this breadth, choices must made in what to amplify and highlight in the analysis. Perhaps because I am a sociologist, what could be developed more – perhaps for another related project – are highlighting the consequences of what happens when nation-states and organizations permit or feed relational inequality mechanisms at the interpersonal, intra-organizational, interorganizational, and transnational levels. When we allow companies and other organizations to, for example, amplify gender inequalities through practices that favor advantaged groups over other groups, what’s diminished, even for the advantaged groups?

Such points appear throughout the book, as sort of bon mots of surprise, described inequality most explicitly with India’s efforts to rectify its stratifying caste system with quotas and Singapore’s efforts to promote meritocracy based on talent. The book also alludes to inequality more subtly with references to Japan’s insularity, particularly regarding immigration and migration. To a less obvious degree, inequality mechanisms are apparent in China’s reliance upon guanxi networks, which favors those who are well-connected. Here, we can see the impact of not channeling talent, whether talent is lost to outright exploitation of labor or social closure efforts that advantage some at the expense of others.

But ultimately individuals, organizations, and nations may not particularly care about how they waste individual and collective human potential. At best, they may signal muted attention to these issues via symbolic statements; at worst, in the pursuit of multiple, competing interests such as consolidating power and resources for a few, they may enshrine and even celebrate practices that deny basic dignities to whole swathes of our communities.

Another area that warrants more highlighting are various nations’ interdependence, transnationally, with various organizations. These include higher education organizations in the US and Europe that train students and encourage research/entrepreneurial start-ups/partnerships. Also, nations are also dependent upon receiving countries’ policies on immigration. This is especially apparent now with the election of publicly elected officials who promote divisions based on national origin and other categorical distinctions, dampening the types and numbers of migrants who can train in the US and elsewhere.

Finally, I wonder what else could be discerned by looking into the state, at a more granular level, as a field of departments and policies that are mostly decoupled and at odds. Particularly in China, we can see regional vs. centralized government struggles.”

During the author-meets-critics session, Ibata-Arens described how nation-states are increasingly concerned about the implications of elected officials upon immigration policy and by extension, transnational relationships necessary to innovation that could be severed if immigration policies become more restrictive.

Several other experts have weighed in on the book’s merits:

“Kathryn Ibata-Arens, who has excelled in her work on the development of technology in Japan, has here extended her research to consider the development of techno-nationalism in other Asian countries as well: China, Singapore, Japan, and India. She finds that these countries now pursue techno-nationalism by linking up with international developments to keep up with the latest technology in the United States and elsewhere. The book is a creative and original analysis of the changing nature of techno-nationalism.”—Ezra F. Vogel, Harvard University

“Ibata-Arens examines how tacit knowledge enables technology development and how business, academic, and kinship networks foster knowledge creation and transfer. The empirically rich cases treat “networked technonationalist” biotech strategies with Japanese, Chinese, Indian, and Singaporean characteristics. Essential reading for industry analysts of global bio-pharma and political economists seeking an alternative to tropes of economic liberalism and statist mercantilism.”—Kenneth A. Oye, Professor of Political Science and Data, Systems, and Society, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

“In Beyond Technonationalism, Ibata-Arens encourages us to look beyond the Asian developmental state model, noting how the model is increasingly unsuited for first-order innovation in the biomedical sector. She situates state policies and strategies in the technonationalist framework and argues that while all economies are technonationalist to some degree, in China, India, Singapore and Japan, the processes by which the innovation-driven state has emerged differ in important ways. Beyond Technonationalism is comparative analysis at its best. That it examines some of the world’s most important economies makes it a timely and important read.”—Joseph Wong, Ralph and Roz Halbert Professor of Innovation Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto

“Kathryn Ibata-Arens masterfully weaves a comparative story of how ambitious states in Asia are promoting their bio-tech industry by cleverly linking domestic efforts with global forces. Empirically rich and analytically insightful, she reveals by creatively eschewing liberalism and selectively using nationalism, states are both promoting entrepreneurship and innovation in their bio-medical industry and meeting social, health, and economic challenges as well.”—Anthony P. D’Costa, Eminent Scholar in Global Studies and Professor of Economics, University of Alabama, Huntsville

my visits to wellesley college

Last week, controversy broke out over Wellesley College’s Freedom Project, a program designed to have students discuss the meaning of freedom through various activities. The program is run by sociologist Tom Cushman and receives much of its funding from the Charles Koch Foundation.

The controversy has a few parts. For example, there is the accusation that Cushman and his staff “silenced” Koch critics. Josh McCabe, a sociologist and assistant dean at Endicott College, pointed out this is simply incorrect. As one of the staff at the Freedom Project, he was directly responsible for the academic programming. For example, in a response to critics in National Review, McCabe points out that he invited a political scientist whose research is highly critical of the Kochs. He also invited a number of sociologists, almost all of whom are political liberal and very likely to be critics of the Koch’s politics. This includes Elizabeth Popp Berman, who writes for this blog, and Cornell sociologist Kim Weeden.

Now, I want to talk about my experience. Twice, I was invited to speak at the Freedom Project. The first time, I spoke about whether social movements promote freedom. I argued that it’s mixed – some do and some don’t. The second time, I gave a talk about the “common grounds” argument for open borders. This is the idea that conservatives and liberals should both be in favor of free migration.

Each time I visited, I came during the winter “intersession.” For about a week, fifteen undergraduates read together, debated, and listen to outside speakers, including myself. When I visited the class, the students were engaged. When I asked about their political leanings, the average would probably be described as “Hillary Clinton” democrat. Of course, I wanted them to agree with my views – but many didn’t and there was much active debate.

I also got to meet other speakers. I did meet many who were conservative and libertarian. But I also sat in on a lecture by one of Wellesley’s philosophy professors, who actually produced arguments *against* unrestricted free speech. I also met Nadya Hajj, who gave an incredibly engaging talk about how people maintain Palestinian economy and community in the occupied territories.

During my last trip, I set aside some time to interview one of the staff at Wellesley’s art museum because I am working on a project about the careers of visual artists. During my interview, I was told that Tom Cushman was one of the faculty members who defended some controversial art that had been brought to the campus a few years back. That is important to know because Professor Cushman is not merely defending his free speech rights, but he defends the rights of others.

That was my experience. The Freedom Project is one professor’s attempt to bring a discussion of freedom to one of America’s greatest colleges. People of many different views and academic disciplines were brought in, the students vigorously debated the issues. It is funded by conservative and libertarians donors. That, by itself, is not a problem as long as donors do not direct the academic content of the unit.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

remaking higher education for turbulent times, wed., march 28, 9am-6pm EDT, Graduate Center

For those of you in NYC (or those who want to watch a promised live webcast at bit.ly/FuturesEd-live http://videostreaming.gc.cuny.edu/videos/livestreams/page1/ with a livestream transcript here: http://www.streamtext.net/player?event=CUNY), the Graduate Center Futures Initiative is hosting a conference of CUNY faculty and students on Wed., March 28, 9am-6pm EDT at the Graduate Center. Our topic is: “Remaking higher education for turbulent times.” In the first session “Higher Education at a Crossroads” at 9:45am EDT, Ruth Milkman and I, along with other panelists who have taught via the Futures Initiative, will be presenting our perspectives on the following questions:

- What is the university? What is the role of the university, and whom does it serve?

- How do political, economic, and global forces impact student learning, especially institutions like CUNY?

- What would an equitable system of higher education look like? What could be done differently?

Ruth and I will base our comments on our experiences thus far with teaching a spring 2018 graduate course about changes in the university system, drawing on research conducted by numerous sociologists, including organizational ethnographers. So far, our class has included readings from:

- Elizabeth Popp Berman and Catherine Paradeise‘s co-edited RSO volume The University Under Pressure

- Tressie McMillan Cottom‘s Lower Ed

- Mitchell Stevens‘s Creating a Class

- Elizabeth A. Armstrong and Laura Hamilton‘s Paying for the Party

- Ellen Berrey‘s The Enigma of Diversity

- Anthony Jack‘s Soc of Ed article “(No) Harm in Asking“

We will discuss the tensions of reshaping long-standing institutions that have reproduced privilege and advantages for elites and a select few, as well as efforts to sustain universities (mostly public institutions) that have served as a transformational engine of socio-economic mobility and social change. More info, including our course syllabus, is available via the Futures Initiatives blog here.

Following our session, two CUNY faculty and staff who are taking our class, Larry Tung and Samini Shahidi will be presenting about their and their classmates’ course projects.

A PDF of the full day’s activities can be downloaded here: FI-Publics-Politics-Pedagogy-8.5×11-web

If you plan to join us (especially for lunch), please RSVP ASAP at bit.ly/FI-Spring18

in NYC spring 2018 semester? looking for a PhD-level course on “Change and Crisis in Universities?”

Are you a graduate student in the Inter-University Doctoral Consortium or a CUNY graduate student?* If so, please consider taking “Change & Crisis in Universities: Research, Education, and Equity in Uncertain Times” class at the Graduate Center, CUNY. This course is cross-listed in the Sociology, Urban Education and Interdisciplinary Studies programs.

Ruth Milkman and I are co-teaching this class together this spring on Tuesdays 4:15-6:15pm. Our course topics draw on research in organizations, labor, and inequality. This course starts on Tues., Jan. 30, 2018.

Here’s our course description:

This course examines recent trends affecting higher education, with special attention to how those trends exacerbate class, race/ethnicity, and gender inequalities. With the rising hegemony of a market logic, colleges and universities have been transformed into entrepreneurial institutions. Inequality has widened between elite private universities with vast resources and public institutions where students and faculty must “do more with less,” and austerity has fostered skyrocketing tuition and student debt. Tenure-track faculty lines have eroded as contingent academic employment balloons. The rise of on-line “learning” and expanding class sizes have raised concerns about the quality of higher education, student retention rates, and faculty workloads. Despite higher education’s professed commitment to diversity, disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups remain underrepresented, especially among faculty. Amid growing concerns about the impact of micro-aggressions, harassment, and even violence on college campuses, liberal academic traditions are under attack from the right. Drawing on social science research on inequality, organizations, occupations, and labor, this course will explore such developments, as well as recent efforts by students and faculty to reclaim higher education institutions.

We plan to read articles and books on the above topics, some of which have been covered by orgtheory posts and discussions such as epopp’s edited RSO volume, Armstrong and Hamilton’s Paying for the Party, and McMillan Cottom’s Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy. We’ll also be discussing readings by two of our guestbloggers as well, Ellen Berrey and Caroline W. Lee.

*If you are a student at one of the below schools, you may be eligible, after filing paperwork by the GC and your institution’s deadlines, to take classes within the Consortium:

Columbia University, GSAS

Princeton University – The Graduate School

CUNY Graduate Center

Rutgers University

Fordham University, GSAS

Stony Brook University

Graduate Faculty, New School University

Teachers College, Columbia University

New York University, GSAS, Steinhardt

the PROSPER Act, the price of college, and eroding public goodwill

The current Congress is decidedly cool toward colleges and the students attending them. The House version of the tax bill that just passed eliminates the deduction on student loan interest and taxes graduate student tuition waivers as income. Both House and Senate bills tax the largest college endowments.

Now we have the PROSPER Act, introduced on Friday. The 500-plus page bill does many things. It kills the Department of Education’s ability to keep aid from going to for-profit schools with very high debt-to-income ratios, or to forgive the loans of defrauded student borrowers . It loosens the rules that keep colleges from steering students into questionable loans in exchange for parties, perks, and other kickbacks.

And it changes the student loan program dramatically, ending subsidized direct loans and replacing them with a program (Federal ONE) that looks more like current unsubsidized loans. Borrowing limits go up for undergrads and down for some grads. The terms for income-based repayment get tougher, with higher monthly payments and no forgiveness after 20 years. Public Service Loan Forgiveness, particularly important to law schools, comes to an end. (See Robert Kelchen’s blog for some highlights and his tweetstorm for a blow-by-blow read of the bill.)

To be honest, this could be worse. Although I dislike many of the provisions, given the Republican higher ed agenda there’s nothing shocking or unexpectedly punitive, like the grad tuition tax was.

Still, between the tax bill and this one, Congress has taken some sharp jabs at nonprofit higher ed. This goes along with a dramatic downward turn in Republican opinion of colleges over the last two years.

Obviously, some of this is a culture war. Noah Smith highlights student protests and the politicization of the humanities and social sciences as the reason opinion has deteriorated. I think there are aspects of this that are problems, but the flames have mostly been fanned by those with a preexisting agenda. There just aren’t that many Reed Colleges out there.

I suspect colleges are also losing support, though, for another reason—one that is much less partisan. That is the cost of college.

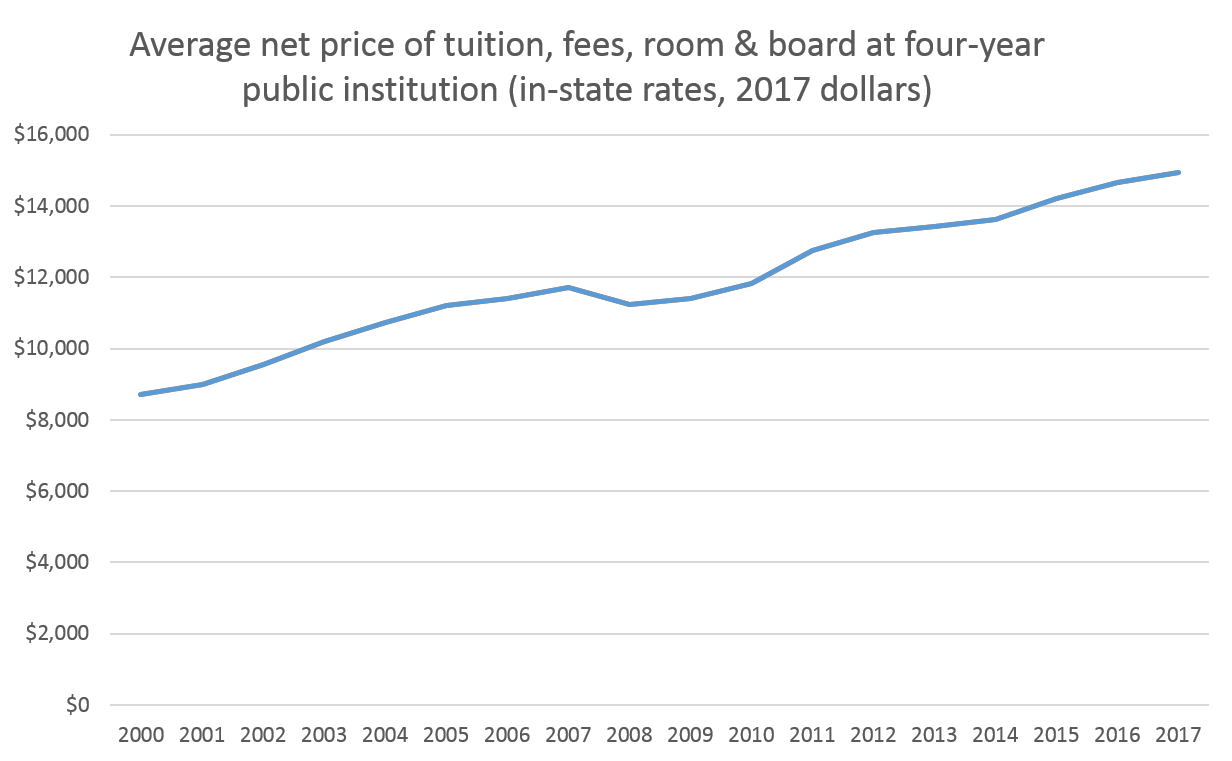

I think colleges have ignored just how much goodwill has been burned up by the rise in college costs. For the last couple of weeks, I’ve been buried in data about tuition rates, net prices, and student loans. Although intellectually I knew how much prices risen, it was still shocking to realize how different the world of higher ed was in 1980.

The entire cost of college was $7,000 a year. For everything. At a four-year school. At a time when the value of the maximum Pell Grant was over $5,000, and the median household income was not far off from today’s. Seriously, I can’t begin to imagine.

The change has been long and gradual—the metaphorical boiling of the frog. The big rise in private tuitions took place in the 90s, but it wasn’t until after 2000 that costs at publics (both sticker price and net price—the price paid after scholarships and grant aid) increased dramatically. Unsurprisingly, student borrowing increased dramatically along with it. The Obama administration reforms, which expanded Pell Grants and improved loan repayment terms, haven’t meant lower costs for students and their families.

What I’m positing is that the rising cost of college and the accompanying reliance on student loans have eroded goodwill toward colleges in difficult-to-measure ways. On the one hand, the big drop in public opinion clearly happened in last two years, and is clearly partisan. Democrats have slightly ticked up in their assessment of college at the same time.

What I’m positing is that the rising cost of college and the accompanying reliance on student loans have eroded goodwill toward colleges in difficult-to-measure ways. On the one hand, the big drop in public opinion clearly happened in last two years, and is clearly partisan. Democrats have slightly ticked up in their assessment of college at the same time.

But I suspect that even support among Democrats may be weaker than it appears, particularly when it comes to bread-and-butter issues, rather than culture-war issues. Only a small minority (22%) of people think college is affordable, and only 40% think it provides good value for the money. And this is the case despite the growing wage gap between college grads and high school grads. Sympathy for proposals that hit colleges financially—whether that means taxing endowments, taxing tuition waivers, or anything else that looks like it will force colleges to tighten their belts—is likely to be relatively high, even among those friendly to college as an institution.

This is likely worsened by the common pricing strategy that deemphasizes the importance of sticker price and focuses on net price. But the perception, as well as the reality, of affordability matters. Today, even community college tuition ($3500 a year, on average) feels like a burden.

The point isn’t whether college is “worth it” in terms of the long-run income payoff. In a purely economic sense there’s no question it is and will continue to be. But pushing the burden of cost onto individuals and families, rather than distributing it more broadly, makes it feel unbearable, and makes people think colleges are just in it for the money. (Which sometimes they are.) I’m always surprised that my SUNY students think the mission of the university is to make money off of them.

This perception means that students and their families and the larger public will be reluctant to support higher education, whether in the form of direct funding, more financial aid, or the preservation of weird but mission-critical perks, like not taxing tuition waivers.

The PROSPER Act, should it come to fruition, will provide another test for public institutions. Federal borrowing limits for undergraduates will rise by $2,000 a year, to $7,500 for freshmen, $8,500 for sophomores, and $9,500 for juniors and seniors. If public institutions immediately default to expecting students to take out the new maximum in federal loans each year, they will continue to erode goodwill even among those not invested in the culture wars.

The sad thing is, this is a self-reinforcing cycle. Colleges, especially public institutions, may feel like they have no choice but to allow tuition to climb, then try to make up the difference for the lowest-income students. But by adopting this strategy, they undermine their very claim to public support. Letting borrowing continue to climb may solve budget problems in the short run. In the long run, it’s shooting yourself in the foot.

what nonacademics should understand about taxing graduate school

There are many bad provisions in the proposed tax legislation. This isn’t even the worst of them. But it’s the one that most directly affects my corner of the world. And, unlike the tax deduction for private jets, it’s one that can be hard for people outside of that world to understand.

That proposal is to tax tuition waivers for graduate students working as teaching or research assistants. Unlike graduate students in law or medical or business schools, graduate students in PhD programs generally do not pay tuition. Instead, a small number of PhD students are admitted each year. In exchange for working half-time as a TA or RA, they receive a tuition waiver and are also paid a stipend—a modest salary to cover their living expenses.

Right now, graduate students are taxed on the money they actually see—the $20,000 or so they get to live on. The proposal is to also tax them on the tuition the university is not charging them. At most private schools, or at out-of-state rates at most big public schools, this is in the range of $30,000 to $50,000.

I think a lot of people look at this and say hey, that’s a huge benefit. Why shouldn’t they be taxed on it? They’re getting paid to go to school, for goodness sakes! And a lot of news articles are saying they get paid $30,000 a year, which is already more than many people make. So, pretty sweet deal, right?

Here’s another way to think about it.

Imagine you are part of a pretty typical family in the United States, with a household income of $60,000. You have a kid who is smart, and works really hard, and applies to a bunch of colleges. Kid gets into Dream College. But wait! Dream College is expensive. Dream College costs $45,000 a year in tuition, plus another $20,000 for room and board. There is no way your family can pay for a college that costs more than your annual income.

But you are in luck. Dream College has looked at your smart, hardworking kid and said, We will give you a scholarship. We are going to cover $45,000 of the cost. If you can come up with the $20,000 for room and board, you can attend.

This is great, right? All those weekends of extracurriculars and SAT prep have paid off. Your kid has an amazing opportunity. And you scrimp and save and take out some loans and your family comes up with $20,000 a year so your kid can attend Dream College.

But wait. Now the government steps in. Oh, it says. Look. Dream College is giving you something worth $45,000 a year. That’s income. It should be taxed like income. You say your family makes $60,000 a year, and pays $8,000 in federal taxes? Now you make $105,000. Here’s a bill for the extra $12,000.

Geez, you say. That can’t be right. We still only make $60,000 a year. We need to somehow come up with $20,000 so our kid can live at Dream College. And now we have to pay $20,000 a year in federal taxes? Plus the $7000 in state and payroll taxes we were already paying? That only leaves us with $33,000 to live on. That’s a 45% tax rate! Plus we have to come up with another $20,000 to send to Dream College! And we’ve still got a mortgage. No Dream College for you.

This is the right analogy for thinking about how graduate tuition remission works. The large majority of students who are admitted into PhD programs receive full scholarships for tuition. The programs are very selective, and students admitted are independent young adults, who generally can’t pay $45,000 a year. Unlike students entering medical, law, or business school, many are on a path to five-figure careers, so they’re not in a position to borrow heavily. Most of them already have undergraduate loans, anyway.

The university needs them to do the work of teaching and research—the institution couldn’t run without them—so it pays them a modest amount to work half-time while they study. $30,000 is unusually high; only students in the most selective fields and wealthiest universities receive that. At the SUNY campus where I work, TAs make about $20,000 if they are in STEM and $16-18,000 if they are not. At many schools, they make even less. (Here are some examples of TA/RA salaries.)

Right now, those students are taxed on the money they actually see—the $12,000 to $32,000 they’re paid by the university. Accordingly, their tax bills are pretty low—say, $1,000 to $6,000, including state and payroll taxes, if they file as individuals.

What this change would mean is that those students’ incomes would go up dramatically, even though they wouldn’t be seeing any more money. So their tax bills would go up too—to something like $5,000 to $18,000, depending on their university. Some students would literally see their modest incomes cut in half. The worst case scenario is that you go a school with high tuition ($45,000) and moderate stipends ($20,000), in which case your tax bill as an individual would go up about $13,000. Your take-home pay has just dropped from $17,500 a year to $4,500.

What would the effects of such a change be? The very richest universities might be able to make up the difference. If it wanted to, Harvard could increase stipends by $15,000. But most schools can’t do that. Some schools might try to reclassify tuition waivers to avoid the tax hit. But there’s no straightforward way to do that.

Some students would take on more loans, and simply add another $60,000 of graduate school debt to their $40,000 of undergraduate debt before starting their modest-paying careers. But many students would make other choices. They would go into other careers, or pursue jobs that don’t require as much education. International students would be more likely to go to the UK or Europe, where similar penalties would not exist. We would lose many of the world’s brightest students, and we would disproportionately lose students of modest means, who simply couldn’t justify the additional debt to take a relatively high-risk path. The change really would be ugly.

All this would be to extract a modest amount of money—only about 150,000 graduate students receive such waivers each year—as part of a tax bill that is theoretically, though clearly not in reality, aimed at helping the middle class.

It is important for the U.S. to educate PhD students. Historically, we have had the best university system in the world. Very smart people come from all over the globe to train in U.S. graduate programs. Most of them stay, and continue to contribute to this country long after their time in graduate school.

PhD programs are the source of most fundamental scientific breakthroughs, and they educate future researchers, scholars, and teachers. And the majority of PhD students are in STEM fields. There may be specific fields producing too many PhDs, but they are not the norm, and charging all PhD students another $6,000-$11,000 (my estimate of the typical increase) would be an extremely blunt instrument for changing that.

Academia is a strange and relatively small world, and the effects of an arcane tax change are not obvious if you’re not part of it. But I hope that if you don’t think we should charge families tens of thousands of dollars in taxes if their kids are fortunate enough to get a scholarship to college, you don’t think we should charge graduate students tens of thousands of dollars to get what is basically the same thing. Doing so would basically be shooting ourselves, as a country, in the foot.

[Edited to adjust rough estimates of tax increases based on the House version of the bill, which would increase standard deductions. I am assuming payroll taxes would apply to the full amount of the tuition waiver, which is how other taxable tuition waivers are currently treated. Numbers are based on California residence and assume states would continue not to tax tuition waivers. If anyone more tax-wonky than me would like to improve these estimates, feel free.]

Teaching/research/learning opportunity available in Lebanon

Paul Galatowitsch has an announcement for organizational researchers who are looking to integrate their summer/winter break with teaching, research, and/or learning in Lebanon.

This might be of particular interest those with experience or seeking experience with NGOs, health systems, and refugees:

www.socioanalytics.org and the Short Course in Lebanon is up and ready. I would really like to get some Organizational Sociologists on board…. It’s a great research and service opportunity.

mental health and graduate school: personal reflections

A few weeks ago, The Chronicle of Higher Education ran an article about the effects of graduate school on mental health. On my Facebook feed, I saw some of the normal contrarian response: “If you think graduate school is bad, wait till you are a professor.” I wrote back, “For me, the tenure track was a cake walk compared to the tenure track. I went to a very toxic graduate program.” I meant that in all honesty.

In this post, I want to elaborate on the effects of graduate programs on individual well being from my own perspective. I do so for two reasons. First, I am an advocate of graduate school reform. I think that graduate programs are poorly designed and I also think that my program at Chicago had some serious challenges. Second, mental health and well being are extremely important. If we can be a little more open about it, we can work to make it better.

Let’s start with self-assessment. I consider myself to be well physically and emotionally. I have never been diagnosed with depression or another disorder. Nor do I have the emotional states that suggest that I am not well. I have had personal success and failure, but I seem to respond constructively. People who know me tend to say that I seem mellow and balanced most of the time. I think that is accurate.

However, that changed during the last year of graduate school. For the first time in my life, I spent a long period of time in a highly anxious state. I could barely sleep. I experienced such bad nausea that I lost about 30 lbs. It was bad. To me, it was clear I needed help. I turned to the student counseling center at the University of Chicago.

There were obvious and non-obvious aspects of my experience. The obvious: As I was nearing completion of my graduate program, I was experiencing stress. Getting a job in academia is hard. The non-obvious: I had experienced much worse stress in my life, but had not experienced this decline in well being. Previously, I had all sorts of positive coping mechanisms. This time, I couldn’t eat and was on the path to poor health. What was the difference?

What my counselor claimed was that anxiety is often associated with a lack control. Bad events don’t always trigger anxiety, but people feel anxiety when they think the world is happening “at them” and they have no way to assert agency in the situation. This made sense to me and the counselor suggested a series of actions to help me regain agency. Some were simple. For example, my counselor suggested that I drink water everyday at regular intervals. I continue that ritual to this very day.

Other methods of asserting agency were were specific to my situation. For example, one of the major factors in my anxiety was the fact that one of the my dissertation committee members refused to speak to me for a year, another had simply gone “AWOL” and a third refused to write me a letter of recommendation. Any one of these issues could hobble a student. To have all three happen could be a career killer. Obviously, I had lost control of the situation and I was paranoid and bitter. How could all my years of work go down the drain because two or three people refused to do their job?

To counter these events, which I have no control over, my counselor suggested a few good rituals. For example, to deal with the guy who would not speak to me, I would politely show up at his scheduled office hours and ask if he had any comments on my dissertation. If not, I would simply say “thank you, I’ll check in a few weeks” and follow up on email. By doing this, I was doing something small to assert control and, legally, I was preparing a paper trail showing that I actively sought comments.

After a while, I was able to calm down. It took a while for me to get a response from the faculty, but it happened. But more importantly, I learned that I could take an active role in my mental well-being. I could create structures and rituals and not be victimized by circumstances.

Now, I want to return to the bigger point – how the structures of graduate school impinge on mental health. At the very least, I was going to be stressed out no matter what. There are many more graduate students than job openings. Also, academia is driven by prestige. Thus, if you went to the wrong school, you may have an uphill battle compared to people who went to the right school or who had the “right” advisers. Higher education is a tough business.

Then, on top of that, the culture in many programs and labs is simply toxic. That is what my experience taught me. People can abandon each other, harm each other and humiliate each other with little immediate consequence. That is probably why people seem to have such negative experiences in academia. It is a hard business, but it’s also a business with few options and very little accountability. In other sectors of the economy, quitting and moving is easy. If you have a bad boss, you can quit and move. In academia, quitting a job can easily be the end of a career.

Thus, we shouldn’t be surprised if higher education is a work environment that exacerbates mental health challenges. It’s an environment that poses limited options and allows people to act badly with few consequences. People (rightfully) feel as if things are out of control, and, in many cases, they are.

To counter these tendencies, and improve well being, we can do a few simple things. First, in the graduate programs, make sure that “everyone is taken care of.” Plan regular meetings with people. Have norms and concrete benchmarks. You can be critical but supportive as well. Actively make sure that all students are on track. Second, create an environment where people can constructively talk about anxiety, depression and whatever other problems they may have. Third, create rules and norms for students and faculty. Students need to hold up their end of the bargain. But so do faculty. A culture of helping all students, openness about problems, and norms for good behavior and timely work can help make graduate school more of a challenge instead of a health issue.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

want to know how academic books are published? listen to eric

Eric Schwartz, of the Columbia University Press, gives a nice summary of how academic publishing works. From the Emory University Center for Faculty Development and Excellence.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

class and college

When awareness about the impact of socio-economic class was not as prevalent among the public, one exercise I did with my undergraduates at elite institutions was to ask them to identify their class background. Typically, students self-identified as being in the middle class, even when their families’ household incomes/net worth placed them in the upper class. The NYT recently published this article showing the composition of undergraduate students, unveiling the concentration and dispersion of wealth at various higher education institutions.

As a professor who now teaches at the university listed as #2 in economic mobility (second to Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology ), I can testify to the issues that make an uneven playing field among undergraduates. Unlike college students whose parents can “pink helicopter” on their behalf and cushion any challenges, undergraduates at CCNY are supporting their parents (if alive) and other family members, bearing the brunt of crushing challenges. (In a minority of cases, students’ parents might help out, say, with occasional childcare – but more likely, students are caring for sick family members or helping with younger siblings.)

To make the rent and cover other expenses in a high COL city, CCNY students work part-time and full-time, sometime with up to two jobs, in the low-wage retail sector. They do so while juggling a full load of classes because their financial aid will not cover taking fewer classes. For some students, these demands can create a vicious cycle of having to drop out of classes or earning low grades.

I always tell students to let me know of issues that might impact their academic performance. Over the years (and just this semester alone), students have described these challenges:

- long commutes of up to 2 hours

- landlord or housing problems

- homelessness

- repeated absences from class due to hospitalizations, illness/accidents, or doctor visits for prolonged health problems

- self-medicating because of fear about high health care costs for a treatable illness

- anxiety and depression

- childcare issues (CCNY recently closed its on-campus childcare facility for students), such as a sick child who cannot attend school or daycare that day

- difficulties navigating bureaucratic systems, particularly understaffed ones

- inflexible work schedules

These are the tip of the iceberg, as students don’t always share what is happening in their lives and instead, just disappear from class.

For me, such inequalities were graphically summed up by a thank you card sent by a graduating undergraduate. The writer penned the heartfelt wish that among other things (i.e., good health), that I always have a “full belly.” Reflecting this concern about access to food, with the help of NYPIRG, CCNY now has a food pantry available to students.

alumni affairs as institutional stratification

This guest post is by Mikalia Lemonik Arthur, associate professor and chair of sociology at Rhode Island College and a long time friend of the blog. She is an expert in higher education and is the author of Student Activism and Curricular Change in Higher Education.

===

My colleague Fran Leazes and I recently released a report “How Higher Education Shapes The Workforce: A Study of Rhode Island College Graduates,” funded by TheCollaborative. Our college—Rhode Island College—is a public comprehensive college at which 85% of students come from within the state, a figure no other college in our state can come close to matching. Our project was spurred by an interest at the state policy level in why graduates of colleges in our state leave Rhode Island. But, we argue, students who were not Rhode Island residents when they began college may not be best understood as “leaving Rhode Island” when they are often really going home. Thus, tracking our alumni—who really are from Rhode Island—provides a useful window onto both higher education outcomes and workforce development in Rhode Island.

Our project combines data from a number of sources to come to several conclusions about our alumni, including that we actually retain most of them in state. Those who leave often leave in pursuit of graduate degrees. And the majority of our graduates find employment in fields related to their undergraduate major. While the report makes several state-level policy suggestions (invest in public higher education, including expanded graduate degree offerings; better promote the excellent alumni workforce we have available in the state), our research process and findings also highlight the need for comprehensive colleges like ours to invest more substantially in their alumni offices.

Most elite private colleges have robust alumni offices. These offices work hard to maintain alumni connections to the college, largely in order to pursue fundraising opportunities. But elite private colleges know that alumni offices serve other purposes as well. By maintaining excellent databases of their alumni, elite private colleges are easily able to make claims about the percentage of alumni who have earned graduate degrees, the number living in particular geographical areas, and the representation of alumni in key professional fields like medicine or politics. Comprehensive colleges, in contrast, rarely have the resources or staffing in either the alumni office or the institutional research office to gather and maintain such information. Thus, in order to put together our report, we had to employ a team of five undergraduate research assistants, who spent the entire fall semester combing the Internet for biographical data on our sample of alumni.

Of course, it would have made our lives easier if our college already had access to such data. But more importantly, such data would enable our college to tell its story in a more persuasive fashion. Rather than talking about the kinds of outcome measures the performance funding types tend to value (employment and salaries a year after graduation), a robust alumni database would allow us to document the value our college has to our state by highlighting the number of successful professionals, community leaders, volunteers, and others RIC has educated.

Comprehensive colleges are an often-ignored sector of higher education, but we play a vital role in educating the professionals who keep our states moving—the nurses, teachers, social workers, police officers, accountants, small business owners, local politicians, and others. And we are often the most accessible and affordable colleges for working class students who will go on to do great things in our states and beyond. The fact that our alumni affairs offices are under-resourced may not be the type of educational stratification researchers and policymakers pay attention to, but it is a type of educational stratification with consequences for our reputations and our institutions’ funding streams.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

the three student loan crises

Among higher ed policy folks, there’s a counter-conventional wisdom that there is no student loan crisis. For the most part (the story goes), student loans are a good investment that will increase future wages, and students could borrow quite a bit more before the value of the debt might be called into question. Indeed, some have argued that many students are too reluctant to borrow, and should take on more debt.

Just this month, two new pieces came out that reiterate this counter-narrative: a book by Urban Institute economist Sandy Baum, and a report by the Council of Economic Advisers. Yes, everyone agrees the system’s not perfect, and tweaks need to be made. (Susan Dynarski, for example, argues that repayment periods need to be longer.) Fundamentally, though, the system is sound. Or so goes the story.

What can we make of this disconnect between the conventional wisdom—that we are in the throes of a student loan crisis—and this counter-conventional story?

To understand it, it’s worth thinking about three different student loan crises. Or “crises”, depending on your sympathies.

First, there’s the student who has accrued six figures of debt for an undergraduate degree. Ideally, for media purposes, this is a degree in women’s studies, art history, or some other easily-dismissible field. The New York Times specialized in these for a while.

Since student loan debt is not bankruptable, these people really are kind of screwed, although income-based-repayment options have improved their options somewhat. And they make for a dramatic story—as well as lots of moralizing in the comments.

Second, there’s the student who took on debt but didn’t finish a degree. These people often struggle, because their income doesn’t go up much, if at all. In fact, the highest default rates are among those who left school with the smallest debts (< $5000), presumably because they didn’t graduate.

These folks disproportionately attend for-profit institutions, whose degrees have less payoff anyhow, but even more importantly, have abysmal graduation rates. (Community colleges have low graduation rates too, but they’re a lot cheaper.) The debt-but-no-degree people are also kind of screwed, although again, income-based repayment plans can help them a lot, as would a bankruptcy option.

So we’ve got the crisis of people who borrow too much for a four-year degree, and the crisis of people who borrow a little, but don’t complete the degree, often because they’re attending a school whose entire business model is to sign up new students for the purpose of taking their loan money.

These are both problems—even “crises”—but they are solvable. For the first, cap federal loans (including PLUS access) for undergraduate degrees, and make all loans bankruptable, so private lenders are leerier of loaning large amounts to students.

For the second—well, I’d probably be comfortable eliminating aid to for-profits, but let’s say that’s beyond the political pale. Certainly we could place a lot more limitations on which institutions are eligible for federal aid, whether that’s tied to graduation rates, default rates, or some other measure. And, again, making student loans bankruptable would help people who really needed to get a fresh start.

Wait, so what’s the third crisis?

The thing is, these two “crises” may be devastating to individuals, but in societal terms aren’t that big. The six-figure-debt one really drives policy wonks crazy, because every student debt story in the last ten years has led with this person, but the percentage of students who finish four-year degrees with this many loans is very small. Like maybe a couple of percent of borrowers small.*

Proponents of the Counter-Conventional Wisdom (C-CW) take the second group—those who borrow but don’t finish a degree—more seriously. This group is often really hurting, despite having smaller loan balances. But they only make up perhaps 20% of borrowers, and since their balances are relatively low, an even smaller fraction of that $1.4 trillion student loan figure we hear so much about.**

The real question—the one that determines whether you think there’s a third crisis—is how you react to the other 75-80% of borrowers. The C-CW crowd looks at them and says, eh, no crisis. These folks come out with four-year degrees, $20 or $30,000 of government-issued student loan debt, will pay $300 a month or so for ten years, and then move on with their lives. We could argue about how much of a burden this is for them, but it’s clearly not a crisis in the same way it is for the NYU grad with $150k in loans, or for the Capella University dropout trying to pay back $7500 on $10 an hour.

This C-CW is based on the premise that 1) college is a human capital investment that is worth taking on debt for up to the expected economic payoff, 2) individual borrowing is a reasonable and appropriate way to finance this investment—indeed, more sensible than paying for the costs collectively—and 3) as long as debt is kept to a “manageable” level (as indicated by students not going into default and having access to forbearance when their income is low), then there’s no crisis.

Why this understates the problem

I take issue with this position, though, on at least three fronts.

1. “Typical” student debt is increasing .

Individual borrowing levels are still rising rapidly, and there’s no reason to think we’ve neared a max. A recent Washington Post editorial cited the CEA report as saying that “[t]he average undergraduate loan burden in 2015 was $17,900.” But that’s not what the average graduate holds. That’s what the average loan-holder holds, including those who have already been paying for a number of years. Estimates for the average 2016 graduate, by contrast, are considerably higher—in the $29,000 to $37,000 range—and growing. The fraction of all students who borrow also continues to increase.

College costs keep rising. State budgets are still under pressure. The penalties for not completing college keep increasing. We can only expect loan sizes to continue to go up. At what point does “reasonable borrowing” become “unreasonable burden”? And tweaks like expanding income-based repayment or extending the standard repayment period won’t bend the curve (to borrow from another debate)—if anything it will enable the further expansion of lending.

2. We are all Capella now.

These debates often overlook the effects of federal aid policy on colleges as organizations, something I’ve written about elsewhere. (The exception is the attention given to the Bennett hypothesis, which suggests that colleges will simply turn federal aid into higher tuition prices.)

But that doesn’t mean organizational effects don’t exist. Continuing to shift the cost burden to individual students is going to accelerate the already intense pressure on public colleges in particular to recruit and retain students, because with students come tuition dollars.

The drive to attract students is already undermining a lot of traditional values in higher education. It encourages schools to spend money on marketing and branding, rather than education. It promotes a consumerist mindset among students who quite reasonably feel that they have become customers. It encourages schools to develop low-value degree programs simply to generate revenue, and recruit students into them regardless of whether the students will benefit.

The values that limit colleges from doing kind of thing are what separates nonprofits from for-profits in the first place. If they go away, we all become Capella. And allowing “reasonable” lending to keep expanding moves us straight in that direction.

3. It gives up on actual public education.

Ultimately, though, the biggest problem I have with this position is that it concedes the possibility, or even the value, of real public higher education entirely. It doesn’t matter whether that’s because the C-CW sees it as a pipe dream, or because it sees it as an irrational use of public funds, since individuals benefit personally from their education in the long run.

This post is already too long, so I won’t go into a detailed defense of public higher ed here. But I do want to point out that if you accept the premise of the C-CW—that student loan debt will only become a crisis if it increases individual costs beyond the returns to a college degree—you’ve already given up on public higher education. I’m not ready to do that.

And it looks like I’m not the only one.

* This number is actually surprisingly difficult to find. In 2008, it was only 0.2% of undergrad completers, but average debt for new graduates has increased about 40% since then, so the six-figure camp has undoubtedly grown.

** Again, exact numbers hard to pin down. 15% of beginning students who borrowed from the government in 2003-04 had not completed a degree six years later, nor were they still enrolled. This figure has doubtless increased as nontraditional borrowers—who are less likely to finish—have become a bigger fraction of the total pool of borrowers, hence my 20% guesstimate.

tenure and promotion experiences among women of color

After completing a Ph.D., how to get a tenure-track position, secure tenure, and advance to full and beyond are not clear, particularly since multiple layers of bureaucracy (committees, department, division, school, and university board) have a say over candidates’ cases. Despite written policies specifying criteria and process for tenure and promotion, universities can interpret these policies in ways that advance or push out qualified candidates. Over at feministwire, Vilna Bashi Treitler shares her experiences with the tenure process at one university, where unofficial teaching evaluations were apparently used to justify a tenure vote: