Archive for the ‘academia’ Category

thriving in the academic commons + labors of love in the time of pandemic

This year, like the past several years, I have the honor of serving as a mentor to tenure-track CUNY faculty in the CUNY Faculty Fellowship Publication Program (FFPP). The FFPP is a writing and professional development program that helps tenure-track faculty at CUNY two-year and four-year colleges navigate the ins-and-outs of publishing and tenure at their teaching and research-intensive universities. As a mentor, I get to read and comment on works in progress, across the disciplines, facilitate group learning processes, and connect with other highly accomplished mentors across CUNY; these responsibilities enact a cooperative philosophy of individual and collective learning-all-the-time.

Since this year’s FFPP orientation was virtual due to the pandemic, FFPP program directors Matt Brim and Kelly Josephs asked me to put together and record a presentation about publishing as a social scientist. I was also asked to comment on publication productivity for scholars who are caregiving during a time of pandemic, state repression/failures, and uncertainty.*

I’m sharing the direct FFPP link to my recorded presentation here in case it might help other scholars outside of CUNY.**

Since the video is not close captioned, I’ve cut and pasted the full script below. While I have embedded screenshots below, here’s my powerpoint presentation if you would like to look at the images of recommended resources, like guides for publication, up close:

“Greetings, I am Katherine K. Chen; I’m an organizational researcher and sociologist at The City College of New York and the Graduate Center, CUNY. I’ve been asked by FFPP to talk about the writing and publication process from the perspective of a social scientist. I’ve also been asked to discuss handling multiple roles in the academic commons during a time of pandemic, austerity, and state repression/failure.

When I was finishing my PhD thesis in graduate school, I came across a book called Deep Survival; in this book, journalist Laurence Gonzales distilled conditions that were common among the accounts of those who had survived disasters, plane crashes, and being lost in remote areas. I think many of these principles are applicable to the academic commons in both conventional times and uncertain times such as these.

I speak as someone who has experiences with journal publishing like the following:

(1) An editor sat on a revision that I submitted in response to a R&R, a revise and resubmit. The editor sat on the revised manuscript for 7 months [correction: it may actually have been 9 months…] before saying he was rejecting it, without sending it out for review. I told other folks I had met at a mini-conference about this dispiriting decision; well, they let a famous researcher who was putting together a special issue around his concept about my paper. That’s how I got introduced to a literature that catapulted my article into a higher ranked, well-known interdisciplinary journal. This scholar also invited me to dialogue with his work for another journal.

(2) I had a journal manuscript that I was absolutely in love with writing, about the difficulties that consumers have with navigating social insurance markets. In Aug. 2013, I sent the manuscript to a special issue for a general journal – this got rejected fairly quickly, with a few helpful review comments. I revised this and sent it to a regional journal in Oct. 2013. This also got rejected in Nov. 2013, with reviews that made it clear at least one reviewer didn’t understand the manuscript. I spent a lot of time revising the manuscript with a new framing, based on a new literature, and submitted to an interdisciplinary journal in July 2016. This version of the manuscript received a R&R; I did a revision. This was followed by another R&R that had the warning of a “high risk” R&R. I did one final push, as this was a make-it-or-break-it moment. For several years, I had spent all of my New Year Eves working on revisions to this paper, and I was hoping to break this yearly ritual, as much as I enjoyed working on the paper. Leading up to this final round, I was doing a reading group with a graduate student on an entirely different topic of school choice, and I also just happened to take the time to read a colleague’s book about the market of wealth management. These seemingly ancillary activities helped me hone my own theoretical concept of bounded relationality, generating a published journal article in highly ranked and regarded journal, more-so than the ones I had originally submitted to.

With these experiences in mind about how long it can take to publish research, I have translated several of the lessons from the Deep Survival book that I mentioned to our specific situations, which is about surviving and hopefully at some point thriving during a long journey towards publication and dissemination.

Here are how these ideas apply to thriving in the academic commons:

- Think relationally. For survivors, the thought of loved ones, real or imagined, was what kept them going on seemingly hopeless treks, even when they were tempted to give up. For academics, thinking relationally means the following: (a) First, who’s your audience? Who are you writing for, and why is it important? (b) Second, who’s in your corner? Who can you turn to for honest feedback? Who can be your cheerleader and supporter? Who can you offer the same in return? Can you form a writing group? Can you find a writing partner? These groups can really keep you going, even when you haven’t heard from reviewers and editors or the reviewer feedback is not what you expect.

- Prepare for your journey by anticipating possibilities. Survivors are prepared with maps and supplies. For academics, this means a lot of reading of examples in your field and how-to guides like: Wendy Belcher’s Writing Your Journal Article in 12 Weeks or William Germano’s From Dissertation to Book.

- Adapt to changing circumstances. In the Deep Survival book, people got into trouble when they acted the way that they thought things should be – that the descent down the mountain should be easy, that there wouldn’t be a storm rolling in. Survivors didn’t reject what they saw or experienced – they adjusted to their conditions. If they were tired, they slept. If they were cold, they didn’t keep wandering around until they got hypothermia; they made a shelter with a fire instead. For academics, this means: (a) If you get a rejection, mourn it for a moment, then keep moving and talking with colleagues, prospective journals, or book publishers. (b) If you keep getting the same advice about your writing, think about how you can use this advice to fix your writing. (c) If you find that your intended audience isn’t receptive to your work, is there a different audience that might welcome your work? Do you need to build up those audiences by organizing conferences or special events and making connections?

- Reflect on where you are by learning a different perspective – The Deep Survival book argues that hikers need to periodically turn around and observe where they were, from a different vantagepoint, so that if and when they need to make a return journey, they can recognize the landscape. This one is a harder one for academics – this is essentially an argument for slow scholarship, for revisiting ideas developed in younger years, to question assumptions and original interpretations, to master different literatures and see how these could fit. Since so many of us have spent years developing expertise in particular areas, it’s tempting to hunker down and take a very linear and narrow path. Adopting different perspectives, crossing subdisciplinary boundaries lines can be generative, help you fall in love again with what originally drew you to research.

Now, I’m going to turn to a slightly different but related topic. Besides working as a tenured faculty, I am also a caregiver for a younger learner – in my case, a 6-year-old daughter and her community of now online learners. What does this mean? I can’t speak as a tenure-track faculty writing during a pandemic; I can only extrapolate from what I am doing and what I worry that junior faculty are experiencing. Here’s my suggestions:

- First, Be kind to yourself.

- Second, Reach out to others for support. Most people and communities do want to be helpful when they can. If you’re not a caregiver yourself, think about how you can support and be inclusive to those who are – Victoria Law and China Martens’ book Don’t Leave Your Friends Behind is a good guide.

- Third, Partner up with others to write.

- Fourth, Use the classroom in synergistic ways – learn about topics and/or methods that you’re interested in and test ideas.

- Five, If you can, use your experience to inform your research and vice versa. I aligned my research interests with what I was experiencing as a parent, instructor, and mentor.

- Six, Take the longterm view – expend your energy interdependently where you think possible futures should head. Many scholars have sought to contribute to the academic commons, in the hope of bettering lives and circumstances for themselves and those around them, despite so many wrenching circumstances. Many of us are the descendants of those who escaped wars, famines, genocides, and slavery, for example, and many of us are here today precisely because of mutual aid and cooperation. Our daily presence and mentorship of upcoming generations are what makes multiple futures possible.

Thank you so much for listening. Take care, and welcome to the CUNY academic commons.”

For other inspiration about writing and publishing, check out other content on the FFPP visual orientation page (some content is embedded, for others, you’ll need to scroll down and click the screenshot images to go to a dropbox link):

- Bridgett Davis recounts her experience with how abandoning 400 pages of writing lead to two additional books, including a memoir that she is now converting into a screenplay for a film.

- William Carr shares how a professional newsletter article about teaching at CUNY lead to an invitation to write about active learning for a textbook, thereby disseminating practices to wider audiences.

- Duke University Press editor Ken Wissoker discusses about publishing dissertation work as books.

- A FFPP group discusses their experiences as “The Writing Group That Never Quit.”

*Incidentally, the pandemic has accelerated skill acquisition and a reliance upon invisible labor and personal resources under challenging conditions. For those of who are instructing virtually from home, we’ve had to learn how to become video content generators, video-makers, and video editors. Some of us must use equipment that we have purchased ourselves and “free” labor donated by others.

** For those of you trying to budget time (or considering asking someone to provide video content), this 8-minute-long video involved several hours of set-up work, including writing and practicing the presentation and fussing with zoom recording and screen sharing settings. I could only complete it because the construction drilling in my complex had finally ended for the day, and I had gotten unpaid technical support from my zoom-savvy 6-year-old assistant. Another uncompensated work assistant (spouse) had sourced, purchased, and set-up the camera and boom mic.

hidden externalities: when failed states prioritize business over education

Much has been discussed in the media about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; for example, to compensate for the absence of coordinated support, working mothers are carrying more caregiving responsibilities. However, the full range of externalities resulting from governmental and organizational decisions (or in the case of some governments, “non”-decisions which are decisions in practice) often are less visible during the pandemic. Some of these externalities – impacts on health and well-being, careers and earnings, educational attainment, etc. – won’t be apparent until much later. The most disadvantaged populations will likely bear the brunt of these; organizations charged with addressing equity issues, such as schools and universities, will grapple over how to respond to these in the years ahead.

In this blog post, I’ll discuss one under-discussed implication of what’s happening in NYC as an example, and how other organizations have had to adjust as a result. Mayor DeBlasio has discussed how NYC public schools will close if NYC’s positivity rate averages 3% over 7 days. At the same time, indoor dining, bars, and gyms have remained open, albeit in reduced capacity. People, especially parents and experts, including medical professionals, are questioning this prioritization of business establishments over schools across the US.

Since the start of the 2020 school year, NYC public schools has offered limited in-person instruction. A few informal conversations I’ve had with parents at NYC public schools revealed that they found the blended option an unviable one. Due to capacity and staffing issues, a public school’s blended learning schedules could vary over the weeks. For example, with a 1:2:2 schedule, a student has 1 day of in person school the first week, followed by 2 days in person the following week, then another 2 days in person the third week. Moreover, which days a student can attend in-person school may not be the same across the weeks. This might partially explain why only a quarter of families have elected these. Overall, both “options” of blended learning and online learning assume that families have flexibility and/or financial resources to pay for help.

What’s the cost of such arrangements? People have already acknowledged that parents, and in particular, mothers, bear the brunt of managing at-home schooling while working from home. But there is another hidden externality that several of my CUNY freshmen students who live with their families have shared with me. While their parents work to pay rent and other expenses, some undergraduates must support their younger siblings’ online learning. Other students are caregiving for relatives, such as a disabled parent, sometimes while recovering from illnesses themselves. Undergraduates must coordinate other household responsibilities in between managing their own online college classes and additional paid work. Without a physical university campus that they can go to for in-person classes (excluding labs and studio classes that are socially distanced) or as study spaces, students don’t have physical buffers that can insulate them against these unanticipated responsibilities and allow them to focus on their learning, interests, and connections.

Drawing on the financial resources available to them and shaping plans around “stabilizing gambits,” several elite universities and small liberal arts colleges have sustained quality education for their students with their in-person classes, frequent testing, and sharing of information among dorm-dwellers. But in the absence of any effective, coordinated federal response to the pandemic in the US, what can public university instructors do to ensure that their undergraduate students have a shot at quality learning experiences? So far, I’ve assigned newly published texts that guide readers through how to more critically analyze systems. I’ve turned to having students documenting their experiences, in the hopes of applying what they have learned to re-design systems that work for more diverse populations. I’ve tried to use synchronous classes as community-building sessions, coupled with feedback opportunities on how to channel our courses to meet their needs and interests. I’ve devoted parts of class sessions to explaining how to navigate the university, including how to select majors and classes and connect with instructors. I’ve connected research skills to interpreting the firehose of statistics and studies about pandemic, to help people ascertain risks so that they can make more informed decisions that protect themselves and their communities and educate others. I’ve attempted to shift expectations for what learning can look like in the absence of face-to-face contact. Since many of the relational dimensions that we took for granted in conventional face-to-face classes are now missing (i.e., visual cues, physical co-presence), I’ve encouraged people to be mutually supportive in other ways, like using the chat / comments function. In between grading and class prep, I’ve written letters of recommendation, usually on very short notice, so that CUNY students can tap needed emergency scholarships or pursue tenure-track jobs. In the meantime, our CUNY programs have tried to enhance outreach as households experience illness and job loss, with emergency funds and campus food pantries mapping where students reside and sending mobile vans to deliver groceries, in an effort to mitigate food insecurity.

Like other scholars, I’ve also revealed, in the virtual classroom, meetings, and conferences, how the gulf between work/family policies is an everyday, shared reality – something that should be acknowledged, rather than hidden away for performative reasons. Eagle-eyed viewers are likely to periodically spot my child sitting by my side in a zoom meeting, assisting me by taking class attendance, or even typing on documents in the background. My capacities to support undergraduate and graduate learning, as well as contribute to the academic commons by reviewing manuscripts and co-organizing academic conferences, have depended on my daughter attending her school in-person. Faculty and staff at her school have implemented herculean practices to make face-to-face learning happen, and families have followed agreements about reducing risks outside of school to maintain in-person learning. That said, given current policy decisions, it’s just a matter of time when I will join other working parents and my CUNY undergraduates making a daily, hour-by-hour complex calculus of what can be done when all-age learners are at home.

All of these adjustments and experimental practices are just baby steps circumnavigating collective issues. These liminal times can offer opportunities to rethink how we enact our supposed values in systems and institutions. For instance, do we allow certain organizations and unresponsive elected leaders to continue to transfer externalities to those who are least prepared to bear them? Do we charge individual organizations and dedicated members, with their disparate access to resources, to struggle with how to serve their populations’ needs? Or, do we more closely examine how can we redesign systems to recognize and support more persons?

umich organizational studies program is hiring

Hey orgtheorists,

On the academic job market? Study organizational types of things? We’re hiring! Org Studies is an interdisciplinary program in the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts at the University of Michigan. Faculty study organizations from a range of social science perspectives (sociology, psychology, political science, management – other fields welcome). I’m chairing the search committee and happy to answer questions about the position, either by email or in the comments. Candidates who can teach organizational behavior and/or leadership are particularly welcome, but the search is definitely open. We would love to see an applicant pool that is diverse along all sorts of dimensions, and we define “organizational” broadly, so don’t rule yourself out. Ad follows, deadline October 1:

Organizational Studies Faculty Position

The University of Michigan Interdisciplinary Program in Organizational Studies solicits applications for a tenure track assistant professorship position to begin September 1, 2020. This is a university-year appointment. The deadline for receiving applications is October 1, 2019. Organizational Studies is a small (approximately 100 students) highly selective undergraduate major in the arts and sciences. We seek applications from a wide range of disciplinary and interdisciplinary backgrounds in the social sciences and professional fields. Candidates must demonstrate excellence in research and teaching related to organizational theory and behavior, broadly defined. We especially seek applicants committed to undergraduate mentorship and innovative teaching methods. Joint appointments with other units at the university are possible. Applications must include cover letter, CV, statement of current and future research plans, writing sample(s), statement of teaching philosophy and experience, and evidence of teaching excellence (evaluations) and syllabi (if available). Please also be prepared to provide the names and contact information for three individuals to contact for confidential letters of reference.

Please follow http://apply.interfolio.com/64458 where you will be able to access the application. For questions, email Orgstudies.Faculty.Search@umich.edu.

The University of Michigan is supportive of the needs of dual career couples and is an equal opportunity / affirmative action employer. Women and minorities are encouraged to apply. The University is committed to diversity, equity, and inclusion (https://diversity.umich.edu/ ), and we encourage applications from candidates who will contribute to furthering these goals.

“don’t be afraid to push big, bold projects” and “be brave and patient”: Dustin Avent-Holt and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey on producing Relational Inequality Theory (RIT)

Dustin Avent-Holt and Donald Tomaskovic-Devey, who collaboratively published their book Relational Inequalities: An Organizational Approach (Oxford University Press), graciously agreed to do a joint email interview with orgtheory! Here, we discuss their book and the process leading up to the production of the book. Readers who are thinking of how to apply relational inequality theory (RIT), join and bridge scholarly conversations, and/or handle collaborative projects, please take note.

First, I asked Dustin and Don substantive questions about RIT. Here, both authors describe how they used their workplaces in higher education as laboratories for refining their theory. Also, Don channeled his disappointment with the limits of Chuck Tilly’s Durable Inequalities into fueling this endeavor.

1. Katherine. How did you apply the insight of relational inequality in your own lives? For example, both of you are at public universities – how does knowing relational inequality affect your ways of interacting with other people and institutions?

Dustin. I think for me one of the ways I see this is becoming faculty during the process of writing the book and being in a transitioning institution. I was hired out of grad school to Augusta University when it had just merged with the Medical College of Georgia. With this merger, Augusta University moved from being a teaching-focused college to a comprehensive research university that includes both graduate and undergraduate programs and a mission focused on research. Experiencing this transition made me think through the daily lives of organizations in a much less structural way as I saw people negotiating and renegotiating the meaning of the institution, the practices and policies, creating new ways of fulfilling institutional roles, etc. I guess in that way it highlighted the work of Tim Hallet on inhabited institutionalism. As university faculty and staff, we didn’t just copy a bunch of templates from the environment, people were translating them and challenging them in the organization. And we still are, 7 years later, and I suspect we will be for a very long time. Organizations at that moment became enactments rather than structures for me, something to be relationally negotiated not simply imported. Don and my endeavor then to understand inequality in this context actually began to make more sense. And in fact during our weekly conversations about the book, I do remember often relating stories to Don of what was going on, and this certainly shaped how I thought about the processes we were thinking through.

I don’t know if that is what you were after in your question, but it is for me this experience shaped how I have come to think about organizations, and became central to how we think about organizations in the book.

Don. No fair, actually apply a theory in our own lives? Seriously though, I became pretty frustrated with the black hole explanations of local inequalities as reflecting “structure” or “history”. These can be analytically useful, but simultaneously disempowering. Yes, some students come to the University with cultural capital that matches some professors, but this does not make them better students, just relationally advantaged in those types of student-teacher interactions. At the same time the University exploits revenue athletes for its purposes while excluding many others from full participation. The struggles of first gen students and faculty are produced by relational inequalities.

As a department chair I was keenly aware of the university dance of claims making around status and revenue and that this had to be actively negotiated if our department was going to be able to claim and sequester resources. This sounds and to some extent is harsh, since success might mean taking resources indirectly from weaker or less strategic departments, although it can also feel insurgent if the resource appears to be granted or extracted from the Provost. But the truth is that university resources flow in a complex network of relationships among units, students, legislators and vendors (beware the new administrative software contract!).

The Dean will pretend this is about your unit’s “productivity”, it’s never that simple.* It’s also great to have allies, at UMass we have a great faculty union that works to level the playing field between departments and disrupt the administrative inequality dance.

* Katherine’s addition: Check out this satirical twitter feed about higher ed administration for laugh/cries.

asa2019 live tweets

With ASA and AOM annual meetings simultaneously happening in NYC and Boston respectively, FOMO is in full swing. In-between spending time with colleagues and helping Fabio pass out Contexts buttons, so far I have live tweeted (with pics!) at my new twitter account @KatherineKChen, a session on “school discipline” and a session on “theoretical perspectives in economic sociology” from ASA.

Sample tweet of the school discipline session, featuring discussant Simone Ispa-Landa‘s comments about where education research should go.

Sample tweet of an economic sociology session summarizes a finding from an analysis of consumer complaints, conducted by Fred Wherry, Parijat Chakrabarti, Isabel Jijon, and Kathleen Donnelly: student debt inflicts “relational damage” on student’s relations with family and employers. epopp’s tweets and take of the same session starts here.

You can find other tweets about ASA using #asa2019 or #asa19 and AOM using #aom2019.

the one where fabio stands up at the end of jess calarco’s job talk and yells, “j’accuse!!”

I was looking for trouble. I’d been drinking ginger ale all day and reading Andy Gelman blog posts. Then, the department email said some hot shot job candidate was giving a talk.

Jess Calarco strolls in Philly stlye and gives her job talk. A forty five minute talk on, of all things, ethnography. Give me a break! Little kids raising their hands, exercising their fancy-schmancy cultural capital. Don’t believe me? Go read it yourself – it’s in a new Oxford University Press book, called Negotiating Opportunity: How the Middle Class Secures Advantages in School. All the gory messy detail in 272 gripping pages of field work. Don’t buy the hardback for $99. Total rip-off. Get the more affordable paper back edition for $24.95!! Those publishers are total con-artists. You gotta be careful.

For the entire talk, Calarco goes on and on about how children from wealthier families negotiate the classroom in small incremental ways through student-teacher interaction. Asking for time on tests, arguing about assignments. What happens at the end of the talk has now become legend at IU soc. This is how Calarco remembers it:

Here is how I remember it. I straightened out my bow tie, I stood up, and asked: “The motivation for your field work is to understand how class based difference in class room interactional style might be linked to learning outcome or status attainment. What evidence do you have from field work that the association is present or explains the variation in outcome, much in the same way a quantitative researcher might use an R-squared to measure a model’s goodness of fit?”

You could hear a pin drop. Children cried. Snowflakes started melting. Then, after taking a few notes, Calarco calmly explains that she was collecting data on the student’s performance to examine the link between classroom behavior and achievement and then she summarized some initial thoughts.

FOILED AGAIN! My plan to undermine the discipline of sociology failed! I went back to my office and vented my frustration on anonymous job rumor websites.

+++++++

BUY THESE BOOKS!!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)

A theory book you can understand!!! Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)

The rise of Black Studies: From Black Power to Black Studies

Did Obama tank the antiwar movement? Party in the Street

Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

fabio’s bill of grad student rights

Last week, I wrote about my practice of asking stiff questions in job talk Q&A’s. Apparently, my questions are responsible for all manner of ill, from gender inequality in academia to something about Bourdieu and social power. To make it up to y’all, I’ll focus on the positive – what I think all graduate school advisers have an obligation to do.

A little background: I spent the early years of my academic career in departments that were very toxic. Lawsuits. Disappearing funding. Masses of junior faculty fleeing. Bad job market placements. Then, I moved to a graduate program that, while not quite as prestigious, was doing just fine. I clearly saw the difference. People often say that they support grad students, but many don’t. Here’s my summary of what effective advisers should be like.

- The right of response: All advisers will promptly respond to emails, dissertation drafts, and other materials. Letters and recommendations will be processed promptly. In academic terms, prompt means a few days, or a week, at most.

- The right of the reminder: All advisers will be open to gentle reminders if they violate #1.

- The right of socialization: All advisers will tell graduate students about the rules and standards of their discipline and relevant sub-fields.

- The right of prompt evaluation: All advisers will write letters of recommendation without complaint and in a prompt fashion, so long as the student gives them sufficient time. In academic terms, sufficient time means about 2-3 weeks.

- The right of civility: All advisers will treat graduate as colleagues in training. There will be no screaming, no belittling behavior, and, of course, advisers will respect the personal space of their students.

- The right of constructive criticism: All advisers retain the right to criticize the academic and professional work of their students. But advisers will deliver all criticism in a calm and professional manner.

- The right of fair warning: If advisers believe that there is a serious issue concerning a student, they shall communicate it early and in a professional manner.

- The right of no land mines: If advisers believe that can’t support the student in their doctoral process or job search, they should express their reservations and recuse themselves.

- The right of the supportive letter of recommendation: Advisers shall write constructive letters that reflect the student’s accomplishments and future trajectory. If the adviser can’t do that, they are bound to issue a “fair warning.” (see Right #7)

- The right of career respect: Advisers will understand that graduate students pursue many different jobs after graduation. The adviser will not belittle students who do not pursue research intensive academic jobs. All students will receive training and support needed to complete their degree in a timely and constructive fashion.

Signed,

Your adviser

+++++++

BUY THESE BOOKS!!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)

A theory book you can understand!!! Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)

The rise of Black Studies: From Black Power to Black Studies

Did Obama tank the antiwar movement? Party in the Street

Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

why i will continue to be annoying at job talks

A couple of days ago, I wrote a blog post about why I think that one should be tough on job candidates during job talks. My argument boils down to a simple point – it’s my chance to push a little and see how they respond in a tough spot.

At first, I was going going to write a blog post defending this view, but then Pamela Oliver retweeted the following, which makes my point very clear:

Bingo. This is exactly right. In your job as a professor, you will be put under pressure. You will be asked uncomfortable questions. They will not care about your feelings or how it conflicts with your sense of egalitarianism. If you read through Professor Michener’s thread, you will see that she handled it in a very thoughtful and professional way. The thread raises many good points, but the starting point is this: this job has moments of pressure and you need to be able to handle it well.

Just to give you a sense of how the “tough Q&A” might be helpful in assessing a person, here are examples of where “thinking on your feet” and “dealing with pressure” made a difference in my own life:

- Around 2000, an audience member at an ASA round table said my work was offensive to all LGBT people. She then stood up and stormed out.

- Around 2008, an audience member at an ASA panel stood up and said that my work was completely wrong. He was referring to a draft of this paper.

- During my midterm review, the current chair indicated that I may be in trouble. It’s ok. I pulled through – we’re still friends!!!

- My work on the More Tweets, More Votes paper was openly criticized by leading political professionals, including this Huffington Post piece.

- I have argued with people in public about open borders. Including the spokesman of the Hungarian national government, Zoltan Kovacs. Let’s just say he doesn’t share my opinion!

- Students will raise potentially inflammatory questions in the middle class. Last year, for example, a student claimed in class that Catholicism is the only true religion. Needed to be real careful about that one.

- The blog generates a surprising amount of hate mail – from other scholars!

- As a journal editor, people question my rejection letters all the time. Oddly, they never question my acceptance letters!

- And of course, the piles and piles of journal and book editor rejections that every professor must deal with.

Of course, the typical day is not that stressful, but scholars are often called to defend themselves and they must do so in the face of tough opposition. I don’t advocate a lack of courtesy or civility. But asking about things like research design, relation to research done by scholars in adjacent fields, and inference is totally acceptable and there is nothing wrong with a courteous, but blunt, question. Heck, IU grads have told me that my questions during practice job talks were excellent prep for job talks elsewhere. Thus, if you have had years to work on a dissertation and you can’t answer a mildly assertive question about your own work, I will not be impressed.

+++++++

BUY THESE BOOKS!!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)

A theory book you can understand!!! Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)

The rise of Black Studies: From Black Power to Black Studies

Did Obama tank the antiwar movement? Party in the Street

Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

why i am annoying at job talks

At my dept, I am the guy who asks the tough questions at the end of the job talks. This strikes people as aggressive or obnoxious and they are right. But I think there is good reason to be extra tough for a job talk.

- Teaching: Can you think on your feet? Most of the time, your students will be asleep. But once in a while, they wake up and they can ask tough questions. You have to be ready for it.

- Actual Contribution: Honestly, PhD program prestige and CVs drive most hiring. Thus, if your adviser makes you author #5 on an AJS or ASR article, you have a massive job market advantage. In that case, I have to see if you actually know what you are talking about, or if you got credit for doing the footnotes.

- Cultishness and Rigor: I want to see if you “drank the kool-aid” or if you really have given serious thought to what you are doing. For example, I love asking qualitative researchers about causal inference. Do they really believe that ethnography is a magic land where inference doesn’t matter? Or have they really thought about what can and can’t be done within a given methodological framework?

- Broad mindedness: Does the person only care about the writings of the two or three most famous people in their sub-area? Or have they thought deeply about what the sub area has accomplished overall? Similarly, are they going off what was the most recent top journal article? Or do they read widely and know they history of their area?

- Disciplinary Parochialism: Does the person only care about what sociologists have written about their topic? Or do they understand the value that other academics might bring to a topic? For example, I routinely ask people doing work/occupations and economic sociology about relevant research in economics.

Of course, no Q&A session can dig into all of these issues. But one or two well placed questions can tell me quite a bit.

+++++++

BUY THESE BOOKS!!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)

A theory book you can understand!!! Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)

The rise of Black Studies: From Black Power to Black Studies

Did Obama tank the antiwar movement? Party in the Street

Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

the contexts editorial method

The Winter 2018 issue of Contexts is out and IT IS FREE until May 3. I’ll take a moment to discuss how Rashawn and I edit Contexts. We are motivated by a few things:

First, Contexts combines two missions – public sociology and scholarly development. Thus, we expect our articles to be interesting and they should also reflect current thinking within the discipline of sociology. So we like articles that have a solid “take home point” and are well written.

Second, we don’t play games with authors. For feature articles, we only ask for a 1 page outline. If we don’t like it, we pass. If we like it, we ask for a full paper that we will peer review. There is only 1 round of peer review. Then, we either reject or accept with revisions. We do things in a matter of weeks, even days.

Third, unlike most journal editors, we actually edit articles. We don’t sit back and wait for reviewers to tell us what we think and say “here are some comments, you figure it out.” We know what we think. We will sit with you and line edit. We will help rewrite. No games, just plain old editing.

You got something to say? Would you like it printed in a beautiful magazine? Send us a proposal. We’d love to read it.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

submitted a paper for an ASA section award? submit it to SocArXiv and be eligible for a SOAR award too

If you’ve submitted a paper to be considered for an American Sociological Association section award – including a graduate student award – consider submitting it to SocArXiv as well. Any paper that is uploaded to SocArXiv by April 30 and wins a 2018 ASA section award will, upon letting us know, receive a supplementary SOAR (Sociology Open Access Recognition) award of $250 in recognition of your achievement. Support open access, gain recognition, and win money all at the same time!

Here’s how it works: You upload your paper to SocArXiv by April 30. If it’s a published paper, check your author agreement or the Sherpa/ROMEO database to see what version, if any, you’re allowed to share. Once you find out you’ve won a section award, email socarxiv@gmail.com. SocArXiv will send you a check for $250, as well as publicizing your paper and officially conferring a SOAR award. That’s the whole deal.

Sharing your paper through SocArXiv is a win-win. It’s good for you, because you get the word out about your research. It’s good for social science, because more people have access to ungated information. And now, with SOAR prizes for award-winning papers, it can be good for your wallet, too. For more information and FAQs visit this link.

minor puzzle about academic hiring

A small puzzle about academic jobs: If getting “the best” is the true purpose of doing a job search, then why do academic programs stop interviewing after the 3rd person? Why it’s a puzzle: There seems to be an over-supply of PhD with good to excellent qualifications. Many never get called out for interviews.

Example: Let’s say you are a top 10 program about to hire an assistant professor. Then what do you look for? You want a graduate of a top 5 (or top 10, maybe) program with one or more hits in AJS/ASR/SF. Perhaps you want someone with a book contract at a fancy press.

You fly out three people. They all turn you down or they suck. The search stops – but this is odd!! These top 5 programs usually produce more than 3 people with these qualifications. Also, add in the fact that every year the market overlooks some really solid people in previous years. My point is simple – departments fly out 2 or 3 people per year but there are usually more than 2 or 3 qualified people!

The puzzle is even more pronounced for low status programs. Why do they stop at 3 candidates when there might be dozens of people with decent publication records who are unclaimed on the market or seriously under-placed? While a top program can wait for the next batch of job market stars, low status programs routinely pass up good people every year.

I have a few explanations, none of which are great. The first is cost – maybe deans and chairs don’t want to pay out more money per year. This makes no sense for top programs which can easily find an extra $1k or $2k for interview costs. For low budget programs, it’s a risk worth taking – that overlooked person could bring in big grant money later. Another explanation is laziness. Good hiring is classic free rider problem. Finding and screening for good people is a cost paid by a few people but the benefits are wide spread. So people do the minimum – fly a few out and move on. Tenure may also contribute to the problem – if you might hire someone for life, you become hyper-selective and only focus on one or two people that survived an intense screening process.

Finally, there may be academic caste. Top programs want an ASR on the CV… but only from people from the “right” schools. This explanation makes sense for top schools, but not for other schools. Why? There are usually quite a few people from good but not elite schools who look great on paper but yet, they don’t get called even though they’d pull up the dept. average.

Am I missing the point? Tell me in the comments! Why is academic hiring so odd?

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

remaking higher education for turbulent times, wed., march 28, 9am-6pm EDT, Graduate Center

For those of you in NYC (or those who want to watch a promised live webcast at bit.ly/FuturesEd-live http://videostreaming.gc.cuny.edu/videos/livestreams/page1/ with a livestream transcript here: http://www.streamtext.net/player?event=CUNY), the Graduate Center Futures Initiative is hosting a conference of CUNY faculty and students on Wed., March 28, 9am-6pm EDT at the Graduate Center. Our topic is: “Remaking higher education for turbulent times.” In the first session “Higher Education at a Crossroads” at 9:45am EDT, Ruth Milkman and I, along with other panelists who have taught via the Futures Initiative, will be presenting our perspectives on the following questions:

- What is the university? What is the role of the university, and whom does it serve?

- How do political, economic, and global forces impact student learning, especially institutions like CUNY?

- What would an equitable system of higher education look like? What could be done differently?

Ruth and I will base our comments on our experiences thus far with teaching a spring 2018 graduate course about changes in the university system, drawing on research conducted by numerous sociologists, including organizational ethnographers. So far, our class has included readings from:

- Elizabeth Popp Berman and Catherine Paradeise‘s co-edited RSO volume The University Under Pressure

- Tressie McMillan Cottom‘s Lower Ed

- Mitchell Stevens‘s Creating a Class

- Elizabeth A. Armstrong and Laura Hamilton‘s Paying for the Party

- Ellen Berrey‘s The Enigma of Diversity

- Anthony Jack‘s Soc of Ed article “(No) Harm in Asking“

We will discuss the tensions of reshaping long-standing institutions that have reproduced privilege and advantages for elites and a select few, as well as efforts to sustain universities (mostly public institutions) that have served as a transformational engine of socio-economic mobility and social change. More info, including our course syllabus, is available via the Futures Initiatives blog here.

Following our session, two CUNY faculty and staff who are taking our class, Larry Tung and Samini Shahidi will be presenting about their and their classmates’ course projects.

A PDF of the full day’s activities can be downloaded here: FI-Publics-Politics-Pedagogy-8.5×11-web

If you plan to join us (especially for lunch), please RSVP ASAP at bit.ly/FI-Spring18

in NYC spring 2018 semester? looking for a PhD-level course on “Change and Crisis in Universities?”

Are you a graduate student in the Inter-University Doctoral Consortium or a CUNY graduate student?* If so, please consider taking “Change & Crisis in Universities: Research, Education, and Equity in Uncertain Times” class at the Graduate Center, CUNY. This course is cross-listed in the Sociology, Urban Education and Interdisciplinary Studies programs.

Ruth Milkman and I are co-teaching this class together this spring on Tuesdays 4:15-6:15pm. Our course topics draw on research in organizations, labor, and inequality. This course starts on Tues., Jan. 30, 2018.

Here’s our course description:

This course examines recent trends affecting higher education, with special attention to how those trends exacerbate class, race/ethnicity, and gender inequalities. With the rising hegemony of a market logic, colleges and universities have been transformed into entrepreneurial institutions. Inequality has widened between elite private universities with vast resources and public institutions where students and faculty must “do more with less,” and austerity has fostered skyrocketing tuition and student debt. Tenure-track faculty lines have eroded as contingent academic employment balloons. The rise of on-line “learning” and expanding class sizes have raised concerns about the quality of higher education, student retention rates, and faculty workloads. Despite higher education’s professed commitment to diversity, disadvantaged racial and ethnic groups remain underrepresented, especially among faculty. Amid growing concerns about the impact of micro-aggressions, harassment, and even violence on college campuses, liberal academic traditions are under attack from the right. Drawing on social science research on inequality, organizations, occupations, and labor, this course will explore such developments, as well as recent efforts by students and faculty to reclaim higher education institutions.

We plan to read articles and books on the above topics, some of which have been covered by orgtheory posts and discussions such as epopp’s edited RSO volume, Armstrong and Hamilton’s Paying for the Party, and McMillan Cottom’s Lower Ed: The Troubling Rise of For-Profit Colleges in the New Economy. We’ll also be discussing readings by two of our guestbloggers as well, Ellen Berrey and Caroline W. Lee.

*If you are a student at one of the below schools, you may be eligible, after filing paperwork by the GC and your institution’s deadlines, to take classes within the Consortium:

Columbia University, GSAS

Princeton University – The Graduate School

CUNY Graduate Center

Rutgers University

Fordham University, GSAS

Stony Brook University

Graduate Faculty, New School University

Teachers College, Columbia University

New York University, GSAS, Steinhardt

one possible policy to address harassment in the academy

It is hard to prevent or control harassment in the academy because graduate students and post-docs often rely exclusively on a single person for professional support. Thus, if your adviser or supervisor acts inappropriately, it is very, very hard to find a replacement without wrecking your career.

This fits with a more general theory that harassment is facilitated by situations where men monopolize a resource. In the academy, we give a monopoly to the adviser or lab directors, in the case of post-docs. This is what prevents many graduate students from lodging complaints. While the university slowly adjudicates a complaint, the adviser can ruin one’s life and there isn’t much you can do.

One possible solution is to institute a policy of “adviser bankruptcy” and an “adviser credit rating.” Bankruptcy is what is sounds like. If the university receives credible evidence that a faculty member is abusing graduate students, their chairmanship of the dissertation committee is dissolved and the university actively seeks a replacement, possibly from another school. This last issue is important. If a whole department is toxic, or the university believes that the faculty will seek revenge within the department, or simply that there is no qualified member within a program, an external chair may be needed.

The credit rating policy is what it sounds like. All graduate faculty start with a “good” rating but if the university receives credible evidence of harassment or other misconduct, they are down graded. Downgraded faculty are suspended from the graduate faculty until (a) all charges are cleared or (b) an appropriate punishment has been served.

I don’t claim that this sort of policy will magically make a severe problem disappear, but it opens up options for victims abuse where there aren’t any right now.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

sociology journal reviewing is dumb (except soc sci and contexts) and computer conference reviewing is the way to go. seriously.

This post is an argument for moving away from the current model of sociology journal reviewing and adopting the computer science model. Before I get into it, I offer some disclaimers:

- I do not claim that the CS conference system is more egalitarian or produces better reviews. Rather, my claim is that it is more efficient and better for science.

- Philip Cohen will often chime in and argue that journals should be abolished and we should just dispense with peer review. I agree, but I am a believer in intermediary steps.

- I do not claim that computer science lacks journals. Rather, that field treats journals as a secondary form of publication and most of the action happens in the conference proceeding format.

- Some journals are very well run – Sociological Science does live up to its promise, for example, as a no nonsense place for publication. I am not claiming that every single journal is lame. Just most of them.

Let’s start. How do most sociology journals operate? It goes something like this:

- A scholarly organization or press appoints an editor, or a team, to run a journal.

- There is a limit on how many articles can be published. Top journals may about only 1 in 20 submitted articles. Many journals desk reject a proportion of the submissions.

- When you submit an article, the editors ask people to review the paper. There are deadlines, but they are routinely broken and people vary wildly in terms of the attention they give to papers.

- When the reviews are written, which can take as short as a few days but as long as a year or more, the editors then make a judgment.

- Most papers with positive reviews and that the editors like go through massive revisions.

- The paper is reviewed again, completely from scratch and often with new reviews.

- If the paper is accepted, then this takes as little as a semester but more like a year or two.

This system made sense in a world of limited resources. But it has many, many flaws. Let’s list them:

- Way too much power in the hands of editors. For example, I was told a day or two ago that a previous editor of a major journal simply desk rejected all papers using Twitter data. A while ago, another editor a major journal just decided she had enough of health papers and started desk rejecting them as well. Maybe these choices are justified, maybe they aren’t.

- Awful, awful reviewer incentives. Basically, we beg cranky over worked people to spend hours reading papers. Some people do a good job, but many are simply bad at it. Even when they try, they may not be the best people to read it.

- Massive time wasting. Basically, we have a system where it is normal for papers to bounce around the journal system *for years.*

- Bloated papers. Many of the major advances in science, in previous ages, where made in 5 and 10 page papers. Now, to head off reviewers, people write massive papers with tons of appendices.

Ok, if the system is lame, then what is the alternative? It is simple and very easy to do: move to peer reviewed conference system of computer sciecne. How does that work?

- Set up a yearly conference.

- Like an editorial board, you recruit a pool of peer reviewers and they commit to peer review *before seeing the papers.* Every year, the conference had new “chairs,” who organize the pool.

- Set hard page/word limits. The computer will not accept papers that are not in the right range.

- Once papers and abstracts are submitted, the reviewers *choose* which papers to review. People can indicate how badly they want a paper and you then allocate.

- Each paper had a “guide” who hounds reviewers and guides conversation

- Set hard deadlines. These will be followed (mostly) because there serious consequences if it doesn’t.

- Papers can then be ranked in terms of reviews and the conference chairs can have final say. Papers are not perfect or make everyone happy. They just have to be in the top X% of papers.

- CS proceedings sometimes allow discussion between reviewers, which can clarify issues.

- Some conferences allow an “R&R” stage. If the paper’s authors think they can respond to reviews, they can submit a “rebuttal.”

- In any case, accepted or revised papers also have to stay under the limit and must be submitted by a hard deadline.

- From submission to acceptance might be 3 months, tops. And this applies to all papers. The processes

Let’s review how this system is superior to the traditional journal system:

- Speed: a paper that may take 2-3 years to find a home in the sociology system, takes about one or two semesters in this system. The reason is that the process concludes quickly for every single paper and there are usually multiple conferences you can try.

- Lack of editorial monopoly: The reviewers and chairs rotate every conference, so if you think you just got a bad draw, just try again next year.

- Conversation: In the CS conference software (easychair.org), reviewers can actually talk to each other to clarify what they think.

- (Slightly) Better Reviews: People can choose which papers to review, which means you are way more likely to get someone who cares. Unlike the current system, papers don’t get orphaned and you are more likely to get someone invested in the process.

- Hard page limits: No bloated papers or response memos. It is tightly controlled.

The system is obviously faster. You get the same variety of good and bad reviews, but it is way, way faster. Papers don’t get orphaned or forgotten at journals and all reviews conclude within about 2 months. Specific editors no longer matter and single gatekeepers don’t bottle neck the system. It is better for science because more papers get out faster.

Rise up – what do you have to lose except your bloated R&Rs?

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

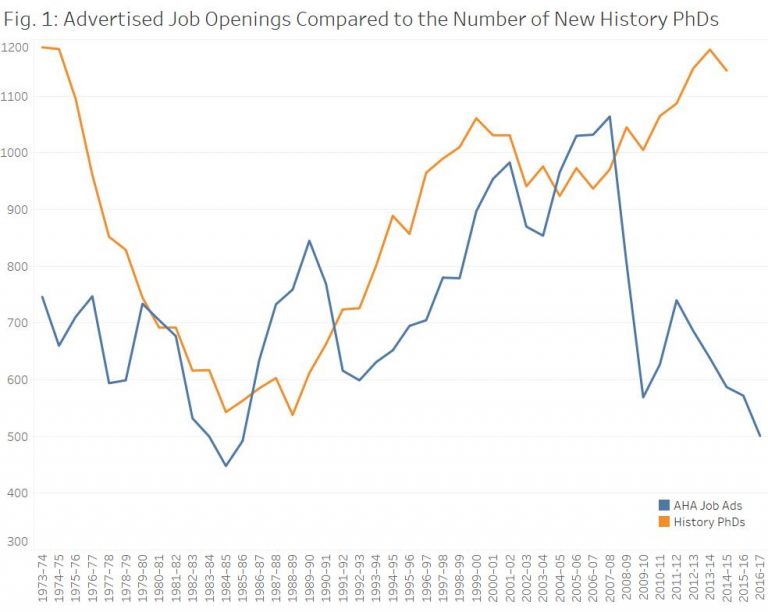

sucks to be a historian

The blog of the American Historical Association has an article about the atrocious state of the job market. Until about 2007, there was a loose correlation between history jobs and history PhDs. Then, a massive drop in history jobs but an increase in history PhD production. Here’s the picture:

Terrible. In some areas, jobs ads are in the single digits. Intellectual history, for example, has two job openings!! The bottom line is that PhD production must be cut back to align with the market. And unlike other fields like economics, and even sociology to some extent, there is very little demand for PhD historians outside universities. Until cut backs happen, history will continue to have one of the worst job markets in the academy.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

what nonacademics should understand about taxing graduate school

There are many bad provisions in the proposed tax legislation. This isn’t even the worst of them. But it’s the one that most directly affects my corner of the world. And, unlike the tax deduction for private jets, it’s one that can be hard for people outside of that world to understand.

That proposal is to tax tuition waivers for graduate students working as teaching or research assistants. Unlike graduate students in law or medical or business schools, graduate students in PhD programs generally do not pay tuition. Instead, a small number of PhD students are admitted each year. In exchange for working half-time as a TA or RA, they receive a tuition waiver and are also paid a stipend—a modest salary to cover their living expenses.

Right now, graduate students are taxed on the money they actually see—the $20,000 or so they get to live on. The proposal is to also tax them on the tuition the university is not charging them. At most private schools, or at out-of-state rates at most big public schools, this is in the range of $30,000 to $50,000.

I think a lot of people look at this and say hey, that’s a huge benefit. Why shouldn’t they be taxed on it? They’re getting paid to go to school, for goodness sakes! And a lot of news articles are saying they get paid $30,000 a year, which is already more than many people make. So, pretty sweet deal, right?

Here’s another way to think about it.

Imagine you are part of a pretty typical family in the United States, with a household income of $60,000. You have a kid who is smart, and works really hard, and applies to a bunch of colleges. Kid gets into Dream College. But wait! Dream College is expensive. Dream College costs $45,000 a year in tuition, plus another $20,000 for room and board. There is no way your family can pay for a college that costs more than your annual income.

But you are in luck. Dream College has looked at your smart, hardworking kid and said, We will give you a scholarship. We are going to cover $45,000 of the cost. If you can come up with the $20,000 for room and board, you can attend.

This is great, right? All those weekends of extracurriculars and SAT prep have paid off. Your kid has an amazing opportunity. And you scrimp and save and take out some loans and your family comes up with $20,000 a year so your kid can attend Dream College.

But wait. Now the government steps in. Oh, it says. Look. Dream College is giving you something worth $45,000 a year. That’s income. It should be taxed like income. You say your family makes $60,000 a year, and pays $8,000 in federal taxes? Now you make $105,000. Here’s a bill for the extra $12,000.

Geez, you say. That can’t be right. We still only make $60,000 a year. We need to somehow come up with $20,000 so our kid can live at Dream College. And now we have to pay $20,000 a year in federal taxes? Plus the $7000 in state and payroll taxes we were already paying? That only leaves us with $33,000 to live on. That’s a 45% tax rate! Plus we have to come up with another $20,000 to send to Dream College! And we’ve still got a mortgage. No Dream College for you.

This is the right analogy for thinking about how graduate tuition remission works. The large majority of students who are admitted into PhD programs receive full scholarships for tuition. The programs are very selective, and students admitted are independent young adults, who generally can’t pay $45,000 a year. Unlike students entering medical, law, or business school, many are on a path to five-figure careers, so they’re not in a position to borrow heavily. Most of them already have undergraduate loans, anyway.

The university needs them to do the work of teaching and research—the institution couldn’t run without them—so it pays them a modest amount to work half-time while they study. $30,000 is unusually high; only students in the most selective fields and wealthiest universities receive that. At the SUNY campus where I work, TAs make about $20,000 if they are in STEM and $16-18,000 if they are not. At many schools, they make even less. (Here are some examples of TA/RA salaries.)

Right now, those students are taxed on the money they actually see—the $12,000 to $32,000 they’re paid by the university. Accordingly, their tax bills are pretty low—say, $1,000 to $6,000, including state and payroll taxes, if they file as individuals.

What this change would mean is that those students’ incomes would go up dramatically, even though they wouldn’t be seeing any more money. So their tax bills would go up too—to something like $5,000 to $18,000, depending on their university. Some students would literally see their modest incomes cut in half. The worst case scenario is that you go a school with high tuition ($45,000) and moderate stipends ($20,000), in which case your tax bill as an individual would go up about $13,000. Your take-home pay has just dropped from $17,500 a year to $4,500.

What would the effects of such a change be? The very richest universities might be able to make up the difference. If it wanted to, Harvard could increase stipends by $15,000. But most schools can’t do that. Some schools might try to reclassify tuition waivers to avoid the tax hit. But there’s no straightforward way to do that.

Some students would take on more loans, and simply add another $60,000 of graduate school debt to their $40,000 of undergraduate debt before starting their modest-paying careers. But many students would make other choices. They would go into other careers, or pursue jobs that don’t require as much education. International students would be more likely to go to the UK or Europe, where similar penalties would not exist. We would lose many of the world’s brightest students, and we would disproportionately lose students of modest means, who simply couldn’t justify the additional debt to take a relatively high-risk path. The change really would be ugly.

All this would be to extract a modest amount of money—only about 150,000 graduate students receive such waivers each year—as part of a tax bill that is theoretically, though clearly not in reality, aimed at helping the middle class.

It is important for the U.S. to educate PhD students. Historically, we have had the best university system in the world. Very smart people come from all over the globe to train in U.S. graduate programs. Most of them stay, and continue to contribute to this country long after their time in graduate school.

PhD programs are the source of most fundamental scientific breakthroughs, and they educate future researchers, scholars, and teachers. And the majority of PhD students are in STEM fields. There may be specific fields producing too many PhDs, but they are not the norm, and charging all PhD students another $6,000-$11,000 (my estimate of the typical increase) would be an extremely blunt instrument for changing that.

Academia is a strange and relatively small world, and the effects of an arcane tax change are not obvious if you’re not part of it. But I hope that if you don’t think we should charge families tens of thousands of dollars in taxes if their kids are fortunate enough to get a scholarship to college, you don’t think we should charge graduate students tens of thousands of dollars to get what is basically the same thing. Doing so would basically be shooting ourselves, as a country, in the foot.

[Edited to adjust rough estimates of tax increases based on the House version of the bill, which would increase standard deductions. I am assuming payroll taxes would apply to the full amount of the tuition waiver, which is how other taxable tuition waivers are currently treated. Numbers are based on California residence and assume states would continue not to tax tuition waivers. If anyone more tax-wonky than me would like to improve these estimates, feel free.]

it’s not you, it’s the job market

It is very hard for young people to not take the job market personally. If you get interviewed and you get turned down, you can always ask: “What could I have done differently?” This is a very bad way to look at things. Why? Because in many cases, you can be perfect and still not get the job. Why? There are way more good candidates than jobs.

A real example. A few years ago, Indiana sociology did a job search in Fish Science.* So we advertised for Fish Scientists and, man, oh man, did we get a great batch of junior level Fish Scientists. The top twenty or thirty Fish Science applicants has pubs in American Fish Review, the American Journal of Fish and Social Fish.** The output of the top ten Fish Scientists would outpace any program in the country. It was amazing. Then we flew out three amazing Fish Scientists. And, once again, they had some amazing Fish research. Solid stuff.

So we settled on a young Fish Scientist and zey turned out amazing. Great colleague, good in the classroom and zey continued to do top notch Fish Science. Sometime last year, I decided to check in on the other junior Fish Scientists. Of course, I couldn’t remember everyone but I did remember a fair number of the top 20. Almost every single one I could remember continued to publish. Some went to other top 10 or 20 programs and have become starts in Fish Science.

Lesson? We often pretend that we picked the #1 absolutist and bestest candidate. But the truth is that many people could do the job and excel. I am happy with the Fish Scientist that we got, but I could easily imagine others doing well in that job or doing well in my job. If you are on the other side, it is easy to tell yourself stories but the truth is that the process is random and noisy. Job markets are like weather patterns, broad in outline but chaotic at the local level.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

*No, it is not an allusion to animals and society, or the person who wrote about the auto-ethnography of playing with their dog. And no, we didn’t do a search in ichthyology.

** Of course, we should also include Fish Problems.***

*** Ok, ok, let’s include Fishography. Happy now?

yes, even mediocre students deserve letters of recommendation

Yes, I believe that letters of recommendation are garbage. But if we continue to require letters, faculty have a moral obligation to write them. Why? Part of being an educator is to evaluate students for the public and as long as they subsidize us professors, we need to satisfy the external demand for assessment.

Sadly, many professors take an opposite view. Students often report that professors turn them down. That happened to me all the time in graduate school. Letters were a precious commodity reserved for the best students. That is simply wrong. In a great post at Scatter, Older Woman explains why you should write letters for most students:

The combination of a high workload per student who needs references and claims that all letters should be excellent or not written at all leads many instructors to refuse to write letters for any but A students or students they know well. But is this fair?

Her answer?

There are a lot of graduate and professional programs out there with widely varying degrees of selectivity. Virtually all of them require three letters of reference for an application to be complete. Getting those three letters is a nightmare for some students because they have trouble tracking down their past instructors and some they do track down refuse to write for them for reasons ranging from the student’s mediocrity to the instructor’s sabbatical or general busyness. I have had conversations in which I tell a student that the letter I could write for them would not be a very good letter and the student would say: I don’t care what it says, I just need three letters. I’ve also talked to honors students who have done independent projects and have one or two excellent letters nailed down who are still desperately shopping for somebody, anybody, to write their third letter, because no matter how good the first two letters are, the application will not be complete without the third.

My view is that all of us who are regular faculty (either tenure track or non-contingent adjuncts) should treat writing letters of reference as an often-annoying but important part of our job. These letters should be honest, and we certainly owe it to the student to tell them honestly if the letter we would be able to write would be tepid or contain negative information that would not help them. We also owe it to the student to ask them about their plans, about their perceptions of the selectivity of the program they are applying to, and whether they have done their homework in selecting a program that fits their qualifications. But if the student feels they want or need the letter anyway after this disclosure and discussion, we should write the letter.

Correct! Basically, letters are not the special property of A students. Many graduate programs simply want to know that the person did decently. Instructors are not required to write special letters for everyone. Most students just want a few sentences explaining that they showed up and did relatively decently. In fact, I think it is totally ok to write one form letter for decent, but not great, students that you can customize as you see fit. It is a requirement for large, public institutions.

Heck, you can even write short and honest letters for crummy students. A real example: In my first year teaching, a dude name Jiffy* asked me for a letter. He was a really weak student. C in intro sociology and seemed spaced out. I said, “sure, but the letter will reflect your current grade – C.” He said that was totally ok. All he wanted was a study abroad letter and all it needed to say was that he attended class and was passing. And so I wrote that letter. All I wrote was a paragraph saying that he showed up to class and would answer questions if called upon. That’s it.

I never did hear back from Jiffy but I Googled him a year ago. He’s now a successful dentist. And you know what, if I helped some dentist enjoy a semester abroad, that’s not a bad thing.

Bottom line: Quit your whining and write that letter. If you don’t think it is part of the job, get another job.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

*Not a real name.

new post-doc program in inequality at harvard

From the home office in Cambridge, Massachusetts, a new post-doc is announced. An excerpt from the program description:

Social and economic inequality are urgent problems for our society, with implications for a range of outcomes from economic growth and political stability to crime, public health, family wellbeing, and social trust. The Inequality in America Initiative Postdoctoral Program seeks applications from recent PhD recipients interested in joining an interdisciplinary network of Harvard researchers who are working to address the multiple challenges of inequality and uncover solutions.

The postdoctoral training program is intended to seed new research directions; facilitate collaboration and mentorship across disciplines; develop new leaders in the study of inequality who can publish at the highest level, reach the widest audience, and impact policy; and deepen teaching expertise on the subject of inequality.

The Award

The fellowship is a two-year postdoctoral training program, with an optional third year conditional on program director approval and independent funding. The salary is $65,000/year plus fringe benefits, including health insurance eligibility.

The award will include appropriate office space; a one-time grant of $2500 for the purchase of computer equipment; a $10,000 research account to support research-related expenses; and up to $2500 per year reimbursement for research-related travel.

Check it out!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

sociological science v. plos one

A few days ago, the Sociological Science editors released a report that discusses their journal’s performance over the last three years. I was also reading an interview with the editor of PLoS One, Joerg Heber, These two items show how these journals operate in different ways and the long term results of their editorial policy choices. Before I move on, I want to thank each journal for making their work transparent. Sociological Science and PLoS One have shown how to do scientific publishing in ways that make editorial decisions more transparent.

PLoS One: The idea is here is simple. PLoS One will only evaluate papers based on technical criteria and ethical standards. In other words, they only thing that is judged is whether the evidence in the paper actually matches the claim of the paper. No judgment is made about whether it is “high impact.” Basically, if it is competent, it gets published, assuming the authors are willing to pay the fees. Papers are blind reviewed, but authors are given many, many chances to fix flaws until either (a) the author gives up or (b) all flaws are addressed.

Long term impact? PLoS One now publishes about 20,000 papers a year. Acceptance rate? 50% in 2016, down from about 66% in earlier years. PLoS has published fewer papers than before, probably due to the rise of Science Advances (the open access branch of Science). Also, PLoS One has a decent impact factor (2.8 in 2016) given that, by design, they published a lot of marginal materials.

Sociological Science: Also a simple idea – send us a paper, they peer review fast and give you a “yes or no.” There are no revisions. Then, after you pay the publication fee, it goes open access. The result? They get 100-200 papers a year and publish about 20-25% of them. The impact factor is not reported (I may have missed it).

Perhaps the most interesting thing that I saw in the Sociological Science report was an analysis of the “most senior co-author.” They find that 47% of the top co-authors are full professors. This is insane, given that full professors, by design, a small fraction of the population of sociologists and many of them no longer publish because they are deadwood or administrators. Post-docs should be all over Sociological Science since they are desperate for jobs and have a lot of new work. This fits my impression, expressed on Facebook, that Sociological Science tilts towards research that is more established. It makes sense given the editorial model. If you are shooting for well done articles but only give “up or down” decisions with no revision, you select out for older authors and more established work.

A comparison of both journals shows that open access publishing is successful. If you want a public repository of peer reviewed work, the PLoS One is clearly a winner. Sociological Science seems to have taken the position of a well regarded specialty journal, with an emphasis on more established authors. That is good too.

Readers know that I am a “journal pluralist.” I am very happy that we have both of these publications. Three cheers for Sociological Science and three cheers for PLoS One.