Archive for the ‘economics’ Category

james buchanan and the stealth plan for insurance copays

I’ve been thinking about James Buchanan again in light of Jennifer Burns’ new critical review of Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains. (Steve Teles and Henry Farrell both defend their own positions — and their independence from Charles Koch — one last time as well.)

I’m done talking about Democracy in Chains, but Buchanan was on my mind today. I don’t know how much direct influence he had on public policy. He hasn’t come up that much in my work, although obviously public choice arguments bolstered the case for deregulation.

Recently, though, I’ve been trying to wrap my head around health policy a little bit, in part to test whether arguments I’ve worked out looking at other social policy domains apply there as well. And here Buchanan plays an interesting — though quite indirect — role.

Health economics as a field only emerged in the 1960s. After federal health spending shot up with the 1965 passage of Medicare and Medicaid, government became increasingly interested in supporting such research.

One of the early papers that shaped that field — and indeed, the whole policy debate over universal health insurance — was Mark Pauly’s 1968 American Economic Review paper, “The Economics of Moral Hazard.”

The paper points out that individuals who are insured against all health costs are likely to seek out more care, at least of some types, than those who are not insured. Thus insurance that includes no deductible or cost-sharing is likely to result in overuse of care. The argument seems obvious now, but at the time — while familiar to insurers — it was novel in economics.

(Interestingly, in Kenneth Arrow’s comment on the paper, his counterargument to Pauly is basically, “this is why we have norms” — to prevent people from consuming more than they need: “Nonmarket controls, whether internalized as moral principles or externally imposed, are to some extent essential for efficiency.”)

Anyway, Pauly was a student of James Buchanan, and credits Buchanan with turning his attention to health policy. Pauly thought he’d do a thesis on “designing the economic framework for a government-funded voucher system for public education” (ahh, now we’re getting into MacLean territory).

But the passage of Medicare had created new pools of money for health research, and Buchanan suggested Pauly might look at health care instead.

Focused on his studies as well as his new wife, 25-year-old student Pauly was only vaguely aware and not much interested in these outside happenings until his mentor, James M. Buchanan, PhD, explained that the law creating Medicare also provided funds for academic health economics studies. He suggested that Pauly switch his thesis focus from education to health care economics and apply for a federal grant.

“Broadly speaking, I was interested in government and public policy,” Pauly remembers. “But the thing that drew me to health care economics was the money. I wish I could be more noble, but that was the reason. I got the grant and the rest is history.”

Three years later, the moral hazard paper was published. It significantly eroded the economic case for universal health insurance without meaningful cost-sharing—just the sort of plan that Ted Kennedy was then advocating—although economists like Rashi Fein would spend the next decade trying to build support for just such a plan.

The moral hazard argument also led the Office of Economic Opportunity to initiate the RAND Health Insurance Experiment, which was intended to estimate the effects of different pricing structures on healthcare consumption and outcomes.

After a decade of study and nearly $100 million in expenditures, the Health Insurance Experiment found that cost-sharing reduced the use of care without harming outcomes. (There was, of course, much debate over the results.) Employers took note: “The fraction of major companies with cost-sharing insurance plans rose from 30% to 63% in the years immediately following the publication of the experimental results.”

The next couple of decades would see repeated attempts to reform healthcare, but the principle of social insurance — of some kind of broad-based, universal coverage like Medicare — stayed on the margins of health policy conversations, replaced by a focus on cost-sharing, means-testing, and the promotion of competition.

So James Buchanan never got the education vouchers he would have liked, and that MacLean focuses on the context of Virginia’s multiyear desegregation battle. And he hardly would have been a fan of Obamacare, which gave government a sizable new role to play in healthcare. And really, whatever credit — or blame — there is should go to Pauly, not Buchanan. Buchanan was just there with advice at a critical moment.

But maybe, just a little, we can point to James Buchanan for helping to give us the healthcare system—with plenty of copays and high deductibles, and still no universal coverage—that we have today.

[With credit to Zach Griffen, who knows much more than I do about both health economics and health policy, for pointing me in the right direction.]

winter book forum 2018, part 2: what do people actually get out of college?

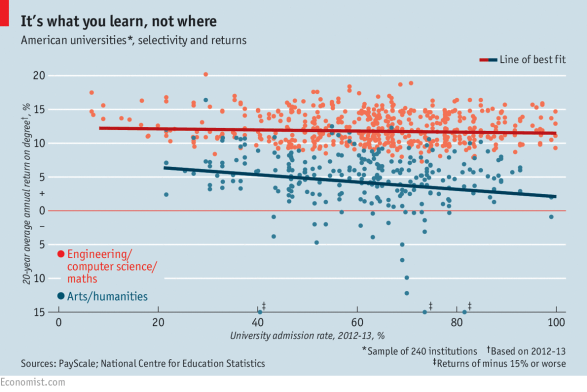

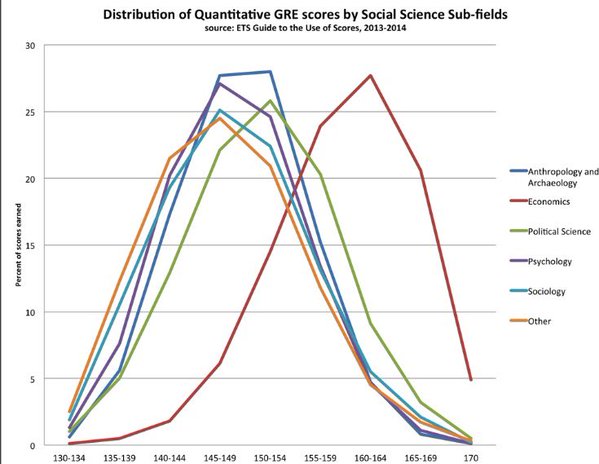

This Winter, we are discussing Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education. The main issue: We invest a ton in education and it seems to do good. But is that because schooling acts as a filter or because schooling gives your concrete skills or better ways of thinking? If education is mostly a filter (the signalling model), we should probably cut back on education a lot.

In this post, I’ll discuss the types of evidence that Caplan reviews. His book is empirical in that the strength of the argument relies on what other researchers have found. A short blog post does not do justice to this work. For example, he asks – how much do people learn in college? How much do people use specific skills (like algebra) in the workplace? Is there any evidence that learning is transferable – that people acquire “critical thinking?” Each of these topics commands one’s full attention, but we can only skim through the best here.

As you can expect from the title of the book, the direct benefits of education are pretty sparse. Probably the most damning evidence are studies that show that people don’t learn that much in college to start with. Another important fact is that few people ever use the skills – the few they may remember – in work. Thus, it is very hard to argue for the simple human capital argument – educations makes you better because you learn valuable things. This can’t be right because people don’t learn or retain much in college.

Two related points: In response to those who argue that education imparts critical thinking, he points to evidence that learning is actually domain specific. Learning one area doesn’t seem to help in most others. This is called “transfer learning” in psychology and it’s been rejected for a long, long time. Another fascinating point – if education improves you via human capital development, we’d expect your income to increase for every year of education you get. Instead, Caplan reports that studies of income show no increase in income until you hit 4 years of college – a classic sign of signalling – which economists call sheepskin effects.

Of course, no single study seals the deal and it may be that Caplan has misread some, or even a lot, of the studies. But is is unlikely he misread it all and it is consistent with the everyday view that formal education is not a particularly good way to impart skills. Thus, we should be very skeptical of claims that education is a great way to train people for the labor market. Next week: So what?

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

winter 2018 book forum: bryan caplan’s the case against education

This month, I will write a series of blog posts about Bryan Caplan’s The Case Against Education: Why the Education System is a Waste of Time and Money. Normally, I will summarize a book, then praise it and then offer some criticism. In this case, I will deviate slightly. A lot of people will criticize the book, so I will focus on describing the core argument and explain why sociologists should care about it. If Caplan’s main point is even partially correct, it has big implications that any educational researcher should care about. In this first installment, I’ll provide a little background and then lay out the main argument. Later this month, I’ll describe the nuts and bolts of the argument in more depth.

I’ve known Bryan for many, many years and I’ve grown a deep appreciation his style of thought. The way he approaches an academic topic is to first boil down the main claim. Then, he will massively research the claim to find out how much of it is true. When I say “massive,” I mean massive. He’ll read across disciplines. He’ll read flagship journals and obscure edited volumes. He’ll even email the authors of papers to make sure that he got their main point correct. Once he is done this obsessive review, he’ll summarize the main points and the then re-assess and redevelop the original claim. He re-estimates models and the draws out the conclusions, which often cut against common opinion.

The Case Against Education proceeds in this same way. Caplan starts with a simple idea that a lot of people believe in: education improves you and that is why it should be subsidized and supported. This basic idea comes in a few flavors. For example, in academia, economists believe in human capital theory – education gives you valuable labor market skills. Other people may believe that education improves you because it makes you a better citizen or it otherwise improves your critical thinking skills. Caplan then contrasts this with another popular theory called “signalling theory” – education doesn’t make you better, but it works as an IQ/conformity test. In other words, people who do well after getting an education aren’t better in any concrete sense. Rather, the college degree is a signal that you are smart to begin with.

Why the emphasis on the human capital/signalling distinction? The theory that you believe in has huge policy implications. If you believe that education gives you a lot of skills and benefits, then it may make sense to pay for a lot of education or to subsidize it. In contrast, you believe it is mostly signalling, it is a sign that you should scale back education.

Then, Caplan delves into hundreds of studies in education, economics, sociology, psychology and other fields to actually see if education actually makes you better, or if it is merely a hoop you have to jump through. For example, is it true that education makes you a better “critical thinker?” It turns out that there is psychological research on “transfer learning,” which means that learning a skill in field A helps you in field B. Answer? Nope, not much transfer learning. Is it true that college graduates learn alot? he reviews work like Richard Arum and Josipina Roska’s Academically Adrift, which shows that people don’t learn a lot in college. The list of debunked effects of education goes on and on.

As you can sense from my thumbnail sketch, Caplan (correctly, in my view) arrives at the conclusion that education doesn’t really make you better in any direct sense. If that is true, then much of education might be a costly and inefficient signalling game and maybe we should seriously consider cutting back on it and that entails a massive change in policy.

Next week: What education does and does not do to a person.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

book spotlight: culture and commerce by mukti khaire

A very, very long time ago, Mukti Khaire was a guest blogger at orgtheory. Since then, she’s been a successful management researcher at the Harvard Business School and Cornell Tech. It is thus a great pleasure for me to read her new book Culture and Commerce: The Value of Entrepreneurship in Creative Industries. The book is a contribution to both the study of art markets and the study of entrepreneurship. The book’s premise is that art and business exist in a sort of fundamental tension. Khaire’s goal is to offer an account of what entrepreneurship means in the world of artistic markets.

The key element of Khaire’s theory is that artistic goods are not only introduced by entrepreneurs, but entrepreneurs do a lot of work to reshape markets so they can accept radically new categories of goods. For example, getting people to accept high quality, but expensive, produce is the work that Whole Foods did in the grocery market about twenty years ago. Such people, who reshape old markets into new markets, Khaire calls “pioneer entrepreneurs.” Similarly, Khaire identifies people who add value because of their ability to provide commentary to products that need explanation.

The strong point of Culture and Commerce is that Khaire digs deeper into the production chain of artistic goods. There are market actors who specialize in bringing in the new products, those who specialize in educating the audience, and those who add quality signals (e.g., giving awards). It’s a very rich account of entrepreneurship that many blog reader will enjoy. Recommended!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

does piketty replicate?

Richard Sutch reports in Social Science History that Piketty does not replicate very well:

This exercise reproduces and assesses the historical time series on the top shares of the wealth distribution for the United States presented by Thomas Piketty in Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Piketty’s best-selling book has gained as much attention for its extensive presentation of detailed historical statistics on inequality as for its bold and provocative predictions about a continuing rise in inequality in the twenty-first century. Here I examine Piketty’s US data for the period 1810 to 2010 for the top 10 percent and the top 1 percent of the wealth distribution. I conclude that Piketty’s data for the wealth share of the top 10 percent for the period 1870 to 1970 are unreliable. The values he reported are manufactured from the observations for the top 1 percent inflated by a constant 36 percentage points. Piketty’s data for the top 1 percent of the distribution for the nineteenth century (1810–1910) are also unreliable. They are based on a single mid-century observation that provides no guidance about the antebellum trend and only tenuous information about the trend in inequality during the Gilded Age. The values Piketty reported for the twentieth century (1910–2010) are based on more solid ground, but have the disadvantage of muting the marked rise of inequality during the Roaring Twenties and the decline associated with the Great Depression. This article offers an alternative picture of the trend in inequality based on newly available data and a reanalysis of the 1870 Census of Wealth. This article does not question Piketty’s integrity.

The point isn’t that income inequality hasn’t risen. Like most social scientists, I am of the view that, for various reasons, income inequality has risen, but it is important to get the magnitudes right, which can support or undermine other hypotheses about wealth accumulation. Sutch’s article shows that Piketty made a good effort, but it depends on some questionable choices. Let there be more discussion of this issue.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

book spotlight: the inner lives of markets by ray fisman and tim sullivan

The Inner Lives of Markets: How People Shape Them and They Shape Us is a “popular economics” book by Ray Fisman and Tim Sullivan. The book is a lively discussion of what one might call the “greatest” theoretical hits of economics. Starting from the early 20th century, Fisman and Sullivan review a number of the major insights from the field of economics. The goal is to give the average person a sense of the interesting insights that economists have come up with as they have worked through various problems such as auction design, thinking about social welfare, behavioral economics, and allocation in a world without prices.

I’ve taken a bit of economics in my life, and I’m somewhat of a rational choicer, so I am quite familiar with the issues that Fisman and Sullivan talk about. I think the best reader for the book might a smart undergrad or a non-economic social scientist/policy researcher who wants a fun and easy tour of more advanced economics. They’ll get lots of interesting stories, like how baseball teams auction off player contracts and how algorithms are used to manage online dating websites.

What I like a lot about the book is that it doesn’t employ the condescending “economic imperialist” approach to economic communication, nor does it offer a Levitt-esque “cute-o-nomics” approach. Rather, Fisman and Sullivan explain the problems that actually occur in real life and then describe how economists have proposed to analyze or solve such issues. In that way, modern economics comes off in a good light – it’s an important toolbox for thinking about the choices that individuals, firms and policy makers must encounter. Definitely good reading for the orgtheorist. Recommended!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome

when was the last time an economist rocked the social sciences?

Question: When was the last time an economist had big impact outside economics? It’s been a while. Gary Becker might be the best example, but that was in the 1970s – forty years ago!!! Of course, there are individual papers or research findings that attract interest (e.g., Deaton’s recent work on mortality), but more recent examples of work that change areas outside economics are hard to find. For example, Steve Levitt is hugely popular, but he hasn’t changed the way people think about areas outside of economics. At best, the big message of early 2000s “cute-o-nomics” is that we can try harder to find clean identification in naturally occurring data. Not a bad message, but not epic, either. And a lot of people were kind of doing that already.

More recently, one might think of Daron Acemoglu, for his massive work on development, or Esther Duflo for field experiments. Both are clearly high impact scholars, but I’d guess that they are high impact within specific areas. You don’t see conferences on the theoretical implications of Duflo or Acemoglu on other disciplines, or even on areas outside of their expertise. Their work doesn’t travel the way Becker’s did, or the way game theory or early econometrics did

Why? Unclear to me. In terms of quality, the average economist is probably stronger than in the past. On the other hand, most of the training in economics programs is on model building. Culturally, economists have developed a disdain for other areas, so they have little incentive to produce work that speaks to anyone except themselves. Then, there are financial incentives. If your salary is way above other disciplines, and you have great job prospects, influencing other fields probably isn’t worth your time. The only thing worth your time is really impressing elites within the field. Not a bad thing per se, but it is not the right environment for work that will reverberate across the academy. Maybe the simplest explanation is low hanging fruit – you have a big impact by bringing a simple idea to an adjacent area. Once that is done, all you are left with are hard problems that only insiders care about.

That’s too bad. I love sociology but I also feel excitement and challenge when a major figure steps up and offers a new way forward. I’d like to see more of it. Not just from sociology, but also from other fields.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome

democracy in chains symposium

Over at Policy Trajectories Josh McCabe has organized a great symposium on Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains, the most dramatic book on public choice theory you are ever likely to read.

Over at Policy Trajectories Josh McCabe has organized a great symposium on Nancy MacLean’s Democracy in Chains, the most dramatic book on public choice theory you are ever likely to read.

Featuring economist Sandy Darity, political scientist Phil Rocco, and your truly, the essays try to get beyond some of the sturm und drang associated with the book’s initially glowing critical reception and intense subsequent backlash. Instead, they ask: How is political orthodoxy produced and challenged? What responsibility do individuals bear when their actions reinforce institutionalized racism? And what explains increasing efforts to put limits on democracy itself?

MacLean’s book may itself be highly polarizing. But the conversations she has opened up will be with us for a long time to come. Check it out.

the democrats can’t decide how radical they want to be on antitrust

The other day I wrote about the current moment in the spotlight for antitrust. (Here’s the latest along these lines from Noah Smith.) Today I’ll say something about the new Democratic proposals on antitrust and how to think about them in terms of the larger policy space.

The Democrats are basically proposing three things. First, they want to limit large mergers. Second, they want active post-merger review. Third, they want a new agency to recommend investigations into anticompetitive behavior. None of these—as long as you don’t go too far with the first—is totally out of keeping with the current antitrust regime. And by that I mean however politically unlikely these proposals may be, they don’t challenge the expert and legal consensus about the purpose of antitrust.

But the language they use certainly does. The proposal’s subhead is “Cracking Down on Corporate Monopolies and the Abuse of Economic and Political Power”. The first paragraph says that concentration “hurts wages, undermines job growth, and threatens to squeeze out small businesses, suppliers, and new, innovative competitors.” The next one states that “concentrated market power leads to concentrated political power.” This is political language, and it goes strongly against the grain of actual antitrust policy.

Economic antitrust versus political antitrust

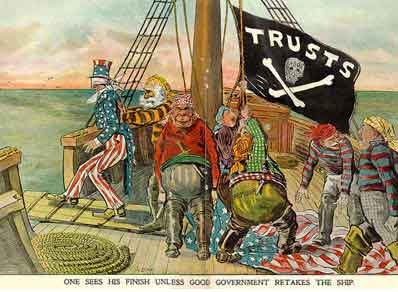

Antitrust has always had multiple, competing purposes. The original Progressive-Era antitrust movement was partly about the power of trusts like Standard Oil to keep prices high. But it was also about more diffuse forms of power—the power of demanding favorable treatment by banks, or the power to influence Congress. That’s why the cartoons of the day show the trusts as octopuses, or as about to throw Uncle Sam overboard.

The Sherman Act (1890) and the Clayton Act (1914), the two major pieces of antitrust legislation, are pretty vague on what antitrust is trying to accomplish. The former outlaws combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade, and monopolizing or attempt to monopolize. The latter outlaws various behaviors if their effect is “substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.” The courts have always played the major role in deciding what that means.

The Sherman Act (1890) and the Clayton Act (1914), the two major pieces of antitrust legislation, are pretty vague on what antitrust is trying to accomplish. The former outlaws combinations and conspiracies in restraint of trade, and monopolizing or attempt to monopolize. The latter outlaws various behaviors if their effect is “substantially to lessen competition, or to tend to create a monopoly.” The courts have always played the major role in deciding what that means.

Throughout the last century, the courts have mostly tried to address the ability of firms to raise prices above competitive levels—the economic side of antitrust. For the last forty years, they have focused specifically on maximizing consumer welfare, often (though not always) defined as allocative efficiency. Since the late 1970s, this has been pretty locked in, both through court decisions, and through strong professional consensus that makes antitrust officials very unlikely to challenge it.

Before the 1970s, though, two things were different. For one thing, the focus was more on protecting competition, and less on consumer welfare per se (the latter was assumed to  follow from the former, and was thought of a little more broadly). For another, the courts sometimes took concerns into account other than keeping prices low.

follow from the former, and was thought of a little more broadly). For another, the courts sometimes took concerns into account other than keeping prices low.

The most common such concern was the fate of small business. Concern for small business motivated the Robinson-Patman Act of 1936, which prohibited anticompetitive price discrimination. It was clear in the Celler-Kefauver Act of 1950, which restricted mergers out of fear that chain stores would eliminate local competition. And the courts acknowledged it in cases like Brown Shoe (1962), which prevented a merger that would have controlled 7% of the shoe market by pointing to Congress’s concern with preserving an “economic way of life” and protecting “local control of industry” and “small business.”

Today, Brown Shoe is seen as part of the bad old days of antitrust, when it was used to protect inefficient small businesses and to pursue confused social goals. This is a strong consensus position among antitrust experts across the political spectrum. While no one thinks that low prices for consumers are the only thing worth pursuing in life, they are the appropriate goal for antitrust because they make it coherent and administrable. Since those experts’ views dominate the antitrust agencies, and have been codified into law through court decisions, they are very resistant to change.

The Democrats’ proposal: radical language, incremental proposals

So when the Democrats start talking about “the abuse of economic and political power,” the effects of concentration on small business, and limiting mergers that “reduce wages, cut jobs, [or] lower product quality,” they are doing two things. First, they are hearkening back to the original antitrust movement, with its complex mix of concerns and its fear of unadulterated corporate power.

Second, they are very much talking about political antitrust, and political antitrust is deeply challenging to the status quo. But their actual proposals are considerably tamer than the fiery language at the beginning, and are structured in a way that doesn’t push very hard on the current consensus. New merger guidelines could make some difference around the margins. Post-merger review would definitely be good, since there’s currently no enforcement of pre-merger conditions that firms agree to, and no good way to figure out which merger approvals had negative effects. I have a hard time seeing a new review agency having much effect, though, since it’s just supposed to make recommendations to other agencies. Even I don’t like bureaucracy that much.

So my read on this is that the Democrats feel like they need a new issue, and it needs to look like it helps the little guy, and they want to sound like populist firebrands. But when you get down to the nitty gritty, they aren’t really so interested in challenging the status quo. That is, basically, they’re Democrats. Still, that the language is in there at all is remarkable, and reflects a changing set of political possibilities.

Next time I’ll look at some of the problems people are suggesting antitrust can solve. Because there are a lot of them, and they’re a diverse group. Tying them together under the umbrella of “antitrust” gives an eclectic political project some nominal coherence. But is it politically practicable? And could it actually work?

Final note: If you are interested in the grand historical sweep of antitrust in capitalism, I recommend Brett Christophers’ The Great Leveler. Among other things, he totally called the emerging wave of interest before it actually happened. Sometimes the very long lens is the right one to use.

why antitrust now?

Antitrust is having a moment. A couple of years ago, with the possible exception of complaining about never-ending airline mergers, no one paid attention to antitrust debates. Today, it’s all over the place. A few months ago, it was the Economist proclaiming “America Needs a Giant Dose of Competition.” Last month it was Amazon and Whole Foods. And now antitrust has become a key plank of the new Democratic platform.

I’ve been thinking about this for a while, but this antitrust explainer written by Matt Yglesias yesterday (which is generally quite good) motivated me to put fingers to keyboard. So I’m going to break this reflection up into three parts: Why antitrust now? What does the new antitrust debate mean? And what would it take for it to succeed? Today, I’ll tackle the first.

At one level, the rise of antitrust interest is just a perfect convening of streams, in the Kingdon sense. A problem (or loose collection of problems) rises to public attention, people are already out there advocating a solution, even if so far unsuccessfully, and—the moment we’re in now—politicians have the motivation to grab that solution and turn it into policy, or at least a platform. It’s just about timing, and it’s not predictable.

At the same time, I think we can unpack a couple of different factors that help us think about “why now”. Some of this is covered in the Yglesias piece. But there are a few things I’d add, and some different angles I’d highlight. So without further ado, here are four reasons antitrust is suddenly getting attention.

1. It’s a reaction to a change in objective conditions.

There is a degree of consensus that market concentration is increasing across the economy. Even if you don’t think concentration is a problem, it wouldn’t be surprising that an increase would lead some people to challenge it, and make media more open to hearing that claim. This is probably a contributing factor. But market concentration has been increasing for a long time, and the link between concentration and exercise of power, whether market power or political power, is at best complicated. I don’t think the rise in concentration explains much of the antitrust attention.

Other phenomena are emerging that are objectively new, and raise new questions about how to govern them. Amazon now controls 43% of internet retail sales in the U.S. That’s astonishing, and at least a little alarming. But we’ve now seen several generations of various platforms (operating systems, browsers, social networks) rise to dominance and sometimes fall, mostly without a lot of antitrust attention—Microsoft, at the turn of the millennium, being the significant exception. These objective changes are a necessary but definitely not sufficient for public attention to rise.

2. New actors are organizing around this issue.

A lot of the noise around antitrust is coming from a relative handful of people. Until the Democrats came on board, it was Elizabeth Warren on the political side, and before that Zephyr Teachout, the Fordham law professor who gave Andrew Cuomo a run for his money in 2014.

On the think tank side, as Yglesias notes, it’s the Open Markets Program at New America. Fellow Lina Khan, once of the Teachout campaign, landed an NYT op-ed on Amazon and Whole Foods. Fellow Matt Stoller’s Atlantic article on antitrust, “How Democrats Killed Their Populist Soul,” got a lot of attention when it came out last fall. Barry Lynn, who runs the program, has been working on this issue for a decade.

The Roosevelt Institute is the other significant player in this space. (Here’s a good, if now difficult to read, piece from last summer explaining the history of Roosevelt.) Marshall Steinbaum and others have made the case for a range of antitrust issues on a variety of grounds, and the influence of both these organizations on the new Democratic congressional platform is clearly visible.

There’s no question that this kind of policy advocacy—talking to policymakers, writing articles and op-eds—is making a difference. But its impact has been facilitated by two other things.

3. The space of expertise is changing in unexpected ways.

Antitrust policy is a space heavily dominated by experts. Congress rarely touches antitrust issues. The public rarely pays attention. Presidents generally talk a good antitrust game, and may care more or less about appointing antitrust officials who will pursue a particular policy line. But for the most part, antitrust is dominated by the lawyers and economists who serve in the Antitrust Division and FTC, consult on antitrust cases, write academic articles, and a handful of whom become judges.

And there is bipartisan consensus among these experts that concentration isn’t generally a problem. Markets are contestable. Predatory pricing is irrational, because firms know that if they drive out competitors then jack up prices, they’ll just attract some new entrant into the market. There’s really no point. Yes, there may be a little more antitrust enforcement among Democrats than Republicans. But it’s a game played “between the 45 yard lines.” As Richard Posner said recently, “Antitrust is dead, isn’t it?”

But this space is changing in interesting ways. The change doesn’t seem to be coming from the antitrust community itself, exactly. But it’s coming from people with the academic clout to be taken seriously.

From one direction, you have people like Jason Furman and Joseph Stiglitz making arguments about labor market monopsony contributing to lower wages and arguing that economic changes require new kinds of antitrust solutions. From another, you have Luigi Zingales overseeing an effort (at the University of Chicago’s Stigler Center, no less) to advocate for stronger antitrust, calling his position “pro-market” rather than “pro-business”. Zingales’ efforts are also notable for bringing in historians, political scientists and other experts usually not privy to the antitrust policy conversation.

None of these people work primarily on antitrust issues or even industrial organization, but they have the status to be taken seriously even if they are not among the usual suspects of antitrust. Their novel arguments have the capacity to shift the expert consensus about antitrust—either mildly, as in Furman’s arguments about the importance of labor monopsony (which don’t require a radical rethinking of the current approach), or more radically, as in Zingales’s advocacy of an antitrust that takes political power seriously.

I’ll discuss these changes more in the next couple of posts, but in terms of explaining “why antitrust now,” the point is that these insider/outsider dissenters are amplifying new voices and new issues, and thus contributing to the current wave of attention.

4. The cultural moment is right for other reasons.

If there’s one belief that seems to unite Americans across the political spectrum these days, it’s that the game is rigged against the ordinary person. For the many Americans who think big business is doing at least some of the rigging, this produces a new openness to arguments about concentration and corporate control. As much as anything else, I think this explains the current interest in antitrust. People are receptive to arguments that purport to explain why they’re being screwed.

Antitrust is a protean issue. It can channel many different types of fears and at least theoretically respond to many different kinds of problems. Whether it can do so effectively, and whether antitrust is the right tool for the job, is a different question. In my next post I’ll try to unpack some of those different problems, why they’re now being linked together under the umbrella of “antitrust,” and draw on some antitrust history to think about what current efforts mean.

why we aren’t behavioral economists: a guest post by nina bandelj, fred wherry, and viviana zelizer

This month is “Money Month” on the blog. We have three utterly amazing and HUGE guests – UC Irvine’s Nina Banelj, Yale’s Fred Wherry and Princeton’s Viviana Zelizer. This first guest post investigates the boundary between economic sociology and allied disciplines.

Rather than retreat to disciplinary corners, let us begin by affirming our respect for the generative work undertaken across a variety of disciplines. We’re all talking money, so it is helpful to specify what’s similar and what’s different when we do. That’s what we tried to do in our just born volume Money Talks: Explaining How Money Really Works where we brought together scholars from sociology, economics, law, political science, anthropology, history, and philosophy. In this post, we address our closest cousins: behavioral economics and cognitive psychology. (Mind you, the first chapter’s author is Jonathan Morduch who has co-authored a widely used economics principles textbook with Dean Karlan. Morduch’s essay in our book develops the first sustained comparison between economic and sociological approaches to money.)

In our introduction to Money Talks, we illustrate differences between mental accounting and relational approaches with the following example. Consider the case of a child’s “college fund.” Marketing professors Soman and Ahn recount the dilemma one of their acquaintances, who is an economist, faced with the option of borrowing money at a high rate of interest to pay for a home renovation or using money he already had saved in his three-year-old son’s low-interest rate education account. As a father, he simply could not go through with the more cost-effective option of “breaking into” his child’s education fund. Soman and Ahn use this story to frame how consequential the emotional content of a particular mental account can be. And by mental account, we mean the “set of cognitive operations used by individuals and households to organize, evaluate, and keep track of financial activities” (Thaler 1999: 183).

How does the sociological approach differ?

Note that when managing these accounts, individuals are really managing their relationships with others. The account is thus relational as well as psychological as individuals engage in what we call relational work. In the anecdote of the college savings account, for instance, we find the parents reluctant to dip into money earmarked for their children’s education. Why? Because these funds represent and reinforce meaningful family ties: they include but transcend individual mental budgeting; the accounts are therefore as relational as they are mental. Suppose a mother gambles away money from the child’s “college fund.” This is not only a breach of cognitive compartments but involves a relationally damaging violation. Most notably, the misspending will hurt her relationship to her child. But the mother’s egregious act is likely to also undermine the relationship to her spouse and even to family members or friends who might sanction harshly the mother’s misuse of money. These interpersonal dynamics thereby help explain why a college fund functions so effectively as a salient relational earmark rather than only a cognitive category.

We hope that the volume and our ongoing discussions this month encourage other scholars to ask how we can compare, contrast, but also complement our sociological approaches with those of behavioral economists and cognitive psychologists.

What will follow will be some focused discussions of how emotions and morality shape money and why all this matters from a policy perspective.

Forward! Adelante! Let’s Talk!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

independent book stores are back!!! a guest post post by clayton childress

Clayton Childress is an Assistant Professor of Sociology at University of Toronto. While making the case for examining the relationships between fields and reuniting the sociological studies of production and reception, Under the Cover empirically follows a works of fiction from start to finish: all the way from its creation, through its production, selling, and reading.

Three Reasons Independent Bookstores Are Coming Back

A couple weeks ago, Fabio had a post about the recent rise in brick-and-mortar independent bookstores, suggesting that perhaps they have successfully repositioned themselves as “artisanal organizations” that thrive through the specialized curation of their stock, and through providing “authentic,” and maybe even somewhat bespoke, book buying experiences for their customers.

There’s some truth to this, but in my forthcoming book, I spend part of a chapter discussing the other factors. Here’s several of them.

Why the return:

1) The Demise of the Borders Group, and Shifting Opportunity Space in Brick-and-Mortar Bookselling.

This graph from Statista in Fabio’s original post starts in 2009, lopping off decades of retrenchment in the number of American Bookseller Association member stores. Despite the recent uptick, independent bookstores have actually declined by about 50% since their peak. More importantly, it’s worth noting that even in the graph we see independent bookstores mostly holding steady from 2009 to 2010, with their rise starting in 2011. Why does this matter? As Dan Hirschman rightly hypothesizes in the comments section of the original post, the bankruptcy and liquidation of the Borders Group began in February of 2011, and is key to any story about the return of independent bookstores. To put some numbers to it, between 2010 and 2011 the Borders Group closed its remaining 686 stores, and between 2010 and 2016 – after spending decades in decline –651 independent bookstores were opened. It’s a pretty neat story of nearly one-to-one replacement between Borders and independents since 2011.*

Yet, if anything, this isn’t as much a surprising story about the continued prevalence of independent bookstores themselves, but rather, a story about the continued prevalence of paper as a medium through which people like to consume the types of books that are mostly sold in independent bookstores. When Borders liquated people didn’t predict that independents would take their place, but that’s because they had mostly misattributed the bankruptcy of Borders to the rise of eBook technology and Amazon. That story was never quite right, though. Borders last year of turning a profit, 2006, mostly predated these supposed causal factors. Instead, Borders’ rise to prominence came through a competitive advantage in their back-end logistics operations, which they then never really updated, and by the mid-2000s they had turned from a market leader to a market trailer. Borders also invested more floor space in selling CDs right when that market started to decline, and then turned that floor space into the selling of DVDs right when that market started to decline – their stores were always too big, and they seemed to have a preternatural ability to keep on filling them with the wrong things. As for the rise of Amazon and online book sales in the decline of Borders, they did play a role, but not the one that people think. In perhaps one of the least prescient moves in the history of American bookselling, as online bookselling started to take off, Borders decided to not spend resources investing in that market, and instead contracted their online bookselling out to Amazon, helping them on their way to dominance of the market. Oh, you dummies.

So, while it was mostly back-end distribution problems, stores that were too big, and a series of bad bets that tanked Borders, its demise was never really about a lack of demand for print books, which allowed independents to fill that market space after Borders disappeared. For independent used book stores (which have always had as much of a supply problem as a demand problem), advances in back end supply systems have in fact made them more viable.

2) Independent Bookstores are the Favored Trading Partners of the Publishing Industry.

Starting during the Great Depression, in order to keep bookstores in business, book publishers began letting them return any (damaged or undamaged) unsold books, meaning that for nothing more than the cost of freight bookstores could pack books up to the ceiling without taking on much financial risk on stocking decisions (if you’ve ever been curious why so many bookstores seem so overstuffed with product, here’s your answer).

It was the beginning of a long history of cooperation between publishers and sellers, and the cooperation has never been more friendly than it is between publishers and independent stores. Publishers and bookstores want the same thing: for people to go into bookstores looking for the books that are actually in stock. With about 300,000 new industry-published books coming out per year, that’s no small feat. For this reason, cooperation between publishers and independents is key, and they rely on an informal system of gift exchange, the details of which I go into in my book.

With the rise of chain bookstores such as Walden, Crown, Barnes & Noble, and Borders, this cooperation became formalized as “co-op,” a system in which publishers nominate their books, and if they are chosen for co-op by the seller, then pay to have their books placed on front tables and endcaps across the country. The basic shorthand is that it costs a publisher about a dollar per copy to get their book on a front table at Barnes & Noble, which is very roughly the same amount that an author gets paid per copy to write the book in her advance (talk to any publisher for long enough and they’ll grind their teeth while noting this).

From the cooperation system with independents the chains developed “co-op”, but a publisher’s relationship with Amazon is closer to coercion. With the chains, publishers can decide to nominate for “co-op” or not, but as soon as publisher sells a book on Amazon they’ve already entered into an enforced “co-op” agreement, in which usually around 6-8% of all of their revenue from selling on Amazon is then withheld, and must be used to advertise on Amazon for future titles. This tends to gets talked about less as “coercion”, and more as “just the way things are” –it’s what happens when you have a retailer that dominates the space enough to set its own terms.

As a result, while book publishers like independent bookstores because they believe them to be owned and staffed by true book lovers (Jeff Bezos was famously disinterested in books when launching Amazon – books are just fairly durable objects of standard size and shape and therefore ship well, making them a good test market for the early days of ecommerce), they also do everything they can to support independent bookstores because their trading terms with them are most favorable to publishers. In their most extreme forms, we can see publishing professionals collaborate in opening their own independent bookstores, but more generally, they engage in subtler forms of support: getting their big name authors to smaller places, and maybe over-donating a little bit to the true cost of printing flyers, and covering the cost of wine and cheese for when the author gets there. Rather than doing this out of the goodness of their hearts, however, publishers do it because independent bookstores are good for them to have around, as they’re the only booksellers who are too small and diffuse to make publishers do things.

3) A Further Reorientation to Niche Specialization at Independents

Here we get to artisanal organizations, and the independent bookstores that are sticking around (or even more importantly, opening) have mostly given up aspirations of being generalists. In Toronto, we’ve got an independent bookstore which specializes in aviation, another for medieval history, and a third which has found a niche for discount-priced theology.* They’re like the Cascade sour beers to Barnes & Noble’s pilsners. While it’s definitely a trend, it’s not one I’d trace back just to 2010, as instead, the artisanal organization market position is one that independent bookstores have been relying on at least back into the 1980s.

In addition to just being niche, while independent hardware stores and grocers were going the way of the dodo, independent bookstores were also able to both capture and foment the formation of the “buy independent” social movements of the 1990s. It’s not many retail outlets that can successfully advocate for their mere existence as a public good. For instance, when was the last time that the New York Times unironically quoted somebody referring to the closing of an independent laundromat halfway across the country as a civic tragedy? As generalist independent bookstores have come to terms with their inability to compete on breadth with Barnes & Noble and Amazon, we see not only a transition to niche sellers, but also more sellers overall, as each one tends to take up a smaller footprint and have lower overhead costs than the independents of the past.

***

Of course, while there has been a rise in the number of independent bookstores in the 2010s, we shouldn’t overstate it, or be certain that it will continue. At the end of the day –and nobody likes to admit this –we’re talking about a segment that makes up less than 10% of industry sales and is still way down from its peak. It took one of the two major brick-and-mortar chains going out of business for this return to happen, but if Barnes & Noble goes under, it will upend any balance left between Amazon and everyone else. Yet unlike the industries for music and journalism, a preference for analog books among a major segment of the market doesn’t seem to be going away. Maybe if Barnes goes under we’ll instead be graphing the rise of brick-and-mortar bookstores by Amazon, and romantically pine for the good old days of Barnes as the industry villain.

*If you’re a cynic, or even just a careful optimist, you’re also going to want to factor in the 80 stores Barnes & Noble has closed since 2010. So, since 2010 that’s a loss of 766 big brick-and-mortar bookstores which were selling a lot of books, and a gain of 655 generally much smaller brick-and-mortar bookstores which are generally selling many fewer books. Yet the number of physical books sold hasn’t really declined, and has actually increased for three years running (for reasons that are the subject of another post). In any case, the difference has been made up by Amazon.

**H/T to Christina Hutchinson and Chanmin Park, two undergraduate students in my Culture, Creativity, and Cities course, for these examples. You can see some of their work on bookstores, as well as other students’ great (and in progress!) work from this semester on Toronto martial arts studios, Korean and Indian restaurants, religious centers, food festivals, and so on here.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($5 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

is ethnography the most policy-relevant sociology?

The New York Times – the Upshot, no less – is feeling the love for sociology today. Which is great. Neil Irwin suggests that sociologists have a lot to say about the current state of affairs in the U.S., and perhaps might merit a little more attention relative to you-know-who.

Irwin emphasizes sociologists’ understanding “how tied up work is with a sense of purpose and identity,” quotes Michèle Lamont and Herb Gans, and mentions the work of Ofer Sharone, Jennifer Silva, and Matt Desmond.

Which all reinforces something I’ve been thinking about for a while—that ethnography, that often-maligned, inadequately scientific method—is the sociology most likely to break through to policymakers and the larger public. Besides Evicted, what other sociologists have made it into the consciousness of policy types in the last couple of years? Of the four who immediately pop to mind—Kathy Edin, Alice Goffman, Arlie Hochschild and Sara Goldrick-Rab—three are ethnographers.

I think there are a couple reasons for this. One is that as applied microeconomics has moved more and more into the traditional territory of quantitative sociology, it has created a knowledge base that is weirdly parallel to sociology, but not in very direct communication with it, because economists tend to discount work that isn’t produced by economics.

And that knowledge base is much more tapped into policy conversations because the status of economics and a long history of preexisting links between economics and government. So if anything I think the Raj Chettys of the world—who, to be clear, are doing work that is incredibly interesting—probably make it harder for quantitative sociology to get attention.

But it’s not just quantitative sociology’s inability to be heard that comes into play. It’s also the positive attraction of ethnography. Ethnography gives us stories—often causal stories, about the effects of landlord-tenant law or the fraying safety net or welfare reform or unemployment policy—and puts human flesh on statistics. And those stories about how social circumstances or policy changes lead people to behave in particular, understandable ways, can change people’s thinking.

Indeed, Robert Shiller’s presidential address at the AEA this year argued for “narrative economics”—that narratives about the world have huge economic effects. Of course, his recommendation was that economists use epidemiological models to study the spread of narratives, which to my mind kind of misses the point, but still.

The risk, I suppose, is that readers will overgeneralize from ethnography, when that’s not what it’s meant for. They read Evicted, find it compelling, and come up with solutions to the problems of low-income Milwaukeeans that don’t work, because they’re based on evidence from a couple of communities in a single city.

But I’m honestly not too worried about that. The more likely impact, I think, is that people realize “hey, eviction is a really important piece of the poverty problem” and give it attention as an issue. And lots of quantitative folks, including both sociologists and economists, will take that insight and run with it and collect and analyze new data on housing—advancing the larger conversation.

At least that’s what I hope. In the current moment all of this may be moot, as evidence-based social policy seems to be mostly a bludgeoning device. But that’s a topic for another post.

hayek and the edge of libertarian reason

I recently had the opportunity to read a whole boat load of F.A. Hayek. Constitution of Liberty; The Use of Knowledge in Society; Law, Legislation and Liberty; and more. This in depth rereading of Hayek helped me resolve a certain sociological puzzle concerning the Austrian economist’s reputation. How could he be the patron saint of laissez-faire while saying very nice things about welfare states and attracting positive commentary from a range of liberal and radical thinkers, such as Foucault?

Here is my answer: I think Hayek’s work resides on a boundary between libertarian social theory and modern liberalism. I’m going to argue that Hayek is the least libertarian you can be and still be, sort of, a libertarian. Because he is not a libertarian in the modern sense of grounding things strongly in terms of individual rights, it’s easy for non-libertarians to find a connection.

Exhibit A: Hayek never lays out a theory of freedom based on individual rights the way many libertarians do. For example, in Constitution of Liberty, he doesn’t start with natural rights and he doesn’t start with a utilitarian justification of freedom. Rather, for him, freedom is about autonomy. Given certain choices, does someone have a sphere of independent judgment free from coercion from others? Thus, this version of freedom is compatible with state policies that try to increase this private sphere of judgment. Also, he frequently emphasizes equality under the law and rule of law as prime virtues, even if they don’t enhance freedom in the everyday sense of the word.

Exhibit B: The Road to Serfdom. It’s a text that is more talked about than read. But if you read it, you discover that it is not an argument against every single form of state intervention. Rather, it’s mainly an argument against Soviet style command economies and Westerners who want to nationalize various industries in the name of equality. Secondarily, he also wants to reign in state regulators who wish to wish to coerce people for their own bureaucratically determined goals.

Exhibit C: In other writings, he endorsed a basic income. And he does argue for the legitimacy of taxation. See Matt Zwolinski’s essay on this topic. He argues that these policies were likely justified for Hayek because they increase personal autonomy (see Exhibit A) and I think they were ok in Hayek’s view because they were less about top down ordering of the economy or administrative tyranny and more about allocating resources to everyone in ways that could help them expand their freedom (Exhibit B).

Exhibit D: Spontaneous order theory. Basically, a whole lot of Hayek’s later social theory is about arguing why social structures can still work and are desirable if they are not top down command structures. That doesn’t lead immediately to libertarianism because you can have spontaneous order that has nothing to do with freedom in either Hayek’s view or the more modern libertarian view. For example, systems of race relations are not top down structures, but they often restrain people in cruel ways.

Taken together, Exhibits A, B, C and D paint an intellectual who has the following traits: (a) Very, very anti-socialist; (b) has a version of freedom that is very agnostic with respect to the wide range of policies that are not socialist; (c) provides grounds for both conservative and liberal policies via a respect for tradition/spontaneous order and freedom/autonomy expansion. It’s a very modest form of libertarianism that gives away a lot of ground to other philosophies.

Does that mean that we’ve all misunderstood Hayek? It depends. If you think that Hayek was this evil economist who advocated the most strict version of libertarianism, then that’s probably mistaken. But if you think of Hayek as a very mellow form of libertarianism that has overlap with other political traditions, you’re probably on target.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

book forum 2017: turco and granovetter

Hi, everyone! As the year winds up, I’d like to announce two book fora:

- March 2017: Catherine Turco’s Conversational Firm.

- May 2017: Mark Granovetter’s Society and Economy.*

Please order the books now!**

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

* Holy smokes, yes, the Granovetter book is coming out. We have heard of this sacred text for years and now… my precious… my precious…

** And yes, editors who read this blog should send me free copies!!

honey, we have to talk about sears

A little while back, I asked how Sears was able to survive as a firm. Once a titan of the American economy, Sears was now a shell of its former self. From a write up in Salon (!) magazine:

Sears Holdings, which owns Sears and Kmart, reported on Thursday a loss of $748 million for the three months ending on Oct. 29. This is the company’s 20th consecutive quarterly loss, and worse than the $454 million loss the company posted in the same period last year. Revenue fell nine percent last quarter to $5.21 billion. Same-store sales, a key retail metric, dropped 10 percent at Sears and 4 percent at Kmart. The company lost $1.6 billion in the first ten months of the year, compared to $549 million in the same period last year, according to its regulatory filing.

These grim numbers were announced a week after the departure of two top-level executives: James Balagna, an executive vice president in charge of the company’s home-repair services and technology backbone, and Joelle Maher, the company’s president and chief member officer. Former Goldman Sachs banker Steve Mnuchinalso resigned from the Sears board last week after President-elect Donald Trump nominated him to head the Treasury Department.

When we discussed Sears, CKD suggested the issue wasn’t firm profitability. It was the relative benefits of bankruptcy court vs. a massive real estate sell off. If so, then the pattern of executive hires and behaviors makes sense. But that raises a deeper point. Why didn’t Sears keep up with the rest of the retail market?

Jeff Sward, founding partner of retail consultant Merchandising Metrics, doesn’t share Hollar’s optimism.

“What does Sears stand for?” Sward told Salon. “Sears unfortunately stands for so many different things that I don’t think there’s anything that’s a standout. I would go to Sears for appliances and tools, but I’ve certainly never thought of them as a headquarters for apparel.”

Sward says the issue isn’t that Sears doesn’t have good products and competitive prices. Instead, he said, the problem facing Sears is that it isn’t the first choice for buyers of any of its core product categories. If consumers need tools, they go to Home Depot or Lowe’s. If they want outdoor or work apparel, it’s Dick’s Sporting Goods, not Sears. Electronics and home appliances? That’s for Best Buy. And who’s buying apparel and shoes at Sears?

The bottom line is that the department store model of the early 1900s is incredibly hard to sustain in the modern environment. Where discovery of the “big box model” by Home Depot and the online model of Amazon, a lot of department store chains either folded or refocused. Sear, with way too much real estate and sluggish executive team, couldn’t make the pivot. Not surprisingly, you then attract investors who are more interested in hollowing out the firm, like the Sears/Kmart holding group that also took on Borders before it died.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

how we abandoned the idea that media should serve the public interest

Yesterday the New Republic wrote about how little attention has been paid to policy in the current election. In 2008, the network news programs devoted 220 minutes to policy; this year, it’s been a mere 32 minutes.

The piece goes on to bemoan the decline of the public-interest obligation once held by broadcasters (and which still remains, in vestigial form) in exchange for their use of the airwaves, and to connect the dots between the gradual removal of those restrictions and the toxic media environment we find ourselves in today. While — I think appropriately — the article doesn’t overemphasize the causal effects, it does highlight a broader shift that was going on in the 1970s and is still echoing today.

The 1970s saw a wide, bipartisan embrace of the deregulatory spirit in many areas. The transportation industries — air, rail, trucking — were one chief target. Banking was in there. So was energy. More controversial, and less bipartisan, was the push for the removal of new social regulations—rules meant improve the environment, health, and safety. But even when it came to social regulation, both sides believed in regulatory reform. (I’ve recently written about some of this history.)

Economists were one group that made a strong case for economic deregulation — the removal of price and entry barriers in industries like transportation, energy, and finance. (For the definitive account, see Martha Derthick and Paul Quirk’s 1985 book.) Their role in airline deregulation, led by the colorful Alfred “To me, they’re all just marginal costs with wings” Kahn, is probably best known. But economists also had something to say about the Federal Communications Commission.

Perhaps the most famous — certainly one of the earliest — critics of the FCC was Ronald Coase. Coase argued in 1959 that there was no good reason, technical or economic, for the government to own the airwaves, and made the case for auctioning off the radio spectrum. He was not at all impressed with the argument that licenses should be distributed according to the “public interest”, and emphasized not only the legal ambiguity of that standard, but the fact that the FCC’s decisions reflected “a degree of inconsistency which defies generalization.”

At the time, the idea of the airwaves as a public trust was so universally accepted that Coase’s views seemed quite radical, even to other economists. When, in 1962, he extended his argument into a 200-page RAND report, coauthored with Bill Meckling and Jora Mirasian, RAND quashed it for being too incendiary. Later, recalling these events, Coase quoted an internal review of the paper: “I know of no country on the face of the globe—except for a few corrupt Latin American dictatorships—where the ‘sale’ of the spectrum could even be seriously proposed.”

By the early 1970s, though, a new consensus had emerged in economics around questions of regulation, and this consensus saw FCC demands that broadcasters behave in unprofitable ways not as acting in the “public interest,” but as a source of efficiency losses that should, at a minimum, be regarded skeptically. This aligned with increasingly loud arguments from outside of economics (as well as within) about regulatory capture, which implied that the “public interest” pursued by executive agencies would never be more than a sham, anyhow.

Eventually, this shift in mood led to a change in how the FCC regulated broadcasters. The public interest standard was loosened, and in 1981 the agency began to shift from using hearings to allocate spectrum licenses — in theory to the applicants that best served the public interest — to lottery. In 1994, it moved another step closer to Coase’s prescription, beginning to auction off the licenses — a move that stimulated a great deal of research in auction theory as well as generating substantial revenue.

The “public interest” goal, which had initially been baked into the allocation process (however poorly it was pursued in practice) became increasingly marginalized. Or perhaps it was subsumed within the assumed public interest in encouraging efficient use of the spectrum. The process echoes the one that took place in antitrust policy, in which historically significant goals other than allocative efficiency — goals that often conflicted with efficiency and even with each other — were gradually defined as being simply beyond the scope of what could be considered. (Indeed, Coase’s criticism of the inconsistency of the FCC’s behavior sounds quite similar to Justice Stewart’s scathing critique of merger law, written around the same time: “the sole consistency I can find is that under Section 7 [the merger section of the Clayton Act], the Government always wins.”)

I don’t know enough about the history of the FCC to have an informed opinion on whether the public interest standard as it stood circa 1970 was redeemable or if the agency was irreparably captured. And I definitely don’t think the decline of that standard is the main explanation for the current media environment, which goes far beyond television.

But I do think that the demise of the idea that we should expect media to have obligations beyond profit — which is bound up with the ideal, if not the practice, of the public interest standard — is a big contributor. Individual journalists — that increasingly rare breed — may remain professionally committed to an ethical code and a sense of mission that isn’t primarily about sales. But at the corporate level, any such qualms were abandoned long ago, and the journalistic wall between “church and state” — editorial and advertising — continues to crumble.

What this means is that we get political news that is just horse race coverage, and endless examination of the ugliest aspects of politics — which, unsurprisingly, encourages more of the same. Actually expecting media to pursue the “public interest”, whether through regulatory means or professional commitment, may be unrealistically idealistic. But giving up on the concept entirely seems certain to take us further down the path in which objective lies merit just as much attention as truth.

no complexity theory in economics

Roger E. Farmer has a blog post on why economists should not use complexity theory. At first, I though he was going to argue that complexity models have been dis-proven or they use unreasonable assumptions. Instead, he simply says we don’t have enough data:

The obvious question that Buzz asked was: are economic systems like this? The answer is: we have no way of knowing given current data limitations. Physicists can generate potentially infinite amounts of data by experiment. Macroeconomists have a few hundred data points at most. In finance we have daily data and potentially very large data sets, but the evidence there is disappointing. It’s been a while since I looked at that literature, but as I recall, there is no evidence of low dimensional chaos in financial data.

Where does that leave non-linear theory and chaos theory in economics? Is the economic world chaotic? Perhaps. But there is currently not enough data to tell a low dimensional chaotic system apart from a linear model hit by random shocks. Until we have better data, Occam’s razor argues for the linear stochastic model.

If someone can write down a three equation model that describes economic data as well as the Lorentz equations describe physical systems: I’m all on board. But in the absence of experimental data, lots and lots of experimental data, how would we know if the theory was correct?

On one level, this is a fair point. Macro-economics is notorious for having sparse data. We can’t re-run the US economy under different conditions a million times. We have quarterly unemployment rates and that’s it. On another level, this is an extremely lame criticism. One thing that we’ve learned is that we have access to all kinds of data. For example, could we have m-turker participate in an online market a million times? Or, could we mine eBay sales data? In other words, Farmer’s post doesn’t undermine the case for complexity. Rather, it suggests that we might search harder and build bigger tools. And, in the end, isn’t that how science progresses?

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

the pager paper, sociological science, and the journal process

Last week, we discussed Devah Pager’s new paper on the correlation between discrimination in hiring and firm closure. As one would expect from Pager, it’s a simple and elegant paper using an audit study to measure the prevalence and consequences of discrimination in the labor market. In this post, I want to use the paper to talk about the journal publication process. Specifically, I want to discuss why this paper appeared in Sociological Science.

First, it may be the case that Professor Pager directly went to Sociological Science without trying another peer reviewed journal. If so, then I congratulate both Pager and Sociological Science. By putting a high quality paper into public access, both Professor Pager and the editors of Sociological Science have shown that we don’t need the lengthy and cumbersome developmental review system to get work out there.

Second, it may be the case that Professor Pager tried another journal, probably the ASR or AJS or an elite specialty journal and it was rejected. If so, that raises an important question – what specifically was “wrong” with this paper? Whatever one thinks of the Becker theory of racial discrimination, one can’t critique the paper on lacking a “framing” or have a simple and clean research design. One can’t critique statistical technique because it’s a simple comparison of means. One can’t critique the importance of the finding – the correlation between discrimination in hiring and firm closure is important to know and notable in size. And, of course, the paper is short and clearly written.

Perhaps the only criticism I can come up with is a sort of “identification fundamentalism.” Perhaps reviewers brought up the fact discrimination was not randomly assigned to firms so you can’t infer anything from the correlation. That is bizarre because it would render Becker’s thesis un-testable. What experimental design would allow you get a random selection of firms to suddenly become racist in their hiring practices? Here, the only sensible approach is Bayesian – you collect high quality observational data and revise your beliefs accordingly. This criticism, if it was made, isn’t sound upon reflection. I wonder what, possibly, could the grounds for rejection be aside from knee jerk anti-rational choice comments or discomfort with a finding that markets do have some corrective to racial discrimination.

Bottom line: Pager and the Sociological Science crew are to be commended. Maybe Pager just wanted this paper “out there” or just got tired of the review process. Either way, three cheers for Pager and the Soc Sci Crew.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

gary becker 1, rational choice haters 0

One of the most striking arguments of Gary Becker’s theory of discrimination is that there is a cost of racial discrimination. If you hire people based on personal taste rather than job skills, your competitors can hire these better works and you work at a disadvantage. I think the strong version argument isn’t right. Markets do not instantly weed out discriminators. But the weak version has a lot of merit. If you truly avoid workers based on race or gender, you are giving away a huge advantage to the competition.

Well, turns out that Becker was right, at least in one data set. Devah Pager has a new paper in Sociological Science showing that discrimination is indeed associated with lower firm performance:

Economic theory has long maintained that employers pay a price for engaging in racial discrimination. According to Gary Becker’s seminal work on this topic and the rich literature that followed, racial preferences unrelated to productivity are costly and, in a competitive market, should drive discriminatory employers out of business. Though a dominant theoretical proposition in the field of economics, this argument has never before been subjected to direct empirical scrutiny. This research pairs an experimental audit study of racial discrimination in employment with an employer database capturing information on establishment survival, examining the relationship between observed discrimination and firm longevity. Results suggest that employers who engage in hiring discrimination are less likely to remain in business six years later.

Commentary: I have always found it ironic that sociologists and non-economists have resisted the implications of taste based discrimination theory. If discrimination in markets is truly not based on performance or productivity, there must be *some* consequence. However, a lot of sociologists have a strong distrust of markets that draws their attention to this rather simple implication of price theory. I don’t know the entire literature on taste based discrimination, but it’s good to see this appear.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

the three student loan crises

Among higher ed policy folks, there’s a counter-conventional wisdom that there is no student loan crisis. For the most part (the story goes), student loans are a good investment that will increase future wages, and students could borrow quite a bit more before the value of the debt might be called into question. Indeed, some have argued that many students are too reluctant to borrow, and should take on more debt.

Just this month, two new pieces came out that reiterate this counter-narrative: a book by Urban Institute economist Sandy Baum, and a report by the Council of Economic Advisers. Yes, everyone agrees the system’s not perfect, and tweaks need to be made. (Susan Dynarski, for example, argues that repayment periods need to be longer.) Fundamentally, though, the system is sound. Or so goes the story.

What can we make of this disconnect between the conventional wisdom—that we are in the throes of a student loan crisis—and this counter-conventional story?

To understand it, it’s worth thinking about three different student loan crises. Or “crises”, depending on your sympathies.

First, there’s the student who has accrued six figures of debt for an undergraduate degree. Ideally, for media purposes, this is a degree in women’s studies, art history, or some other easily-dismissible field. The New York Times specialized in these for a while.

Since student loan debt is not bankruptable, these people really are kind of screwed, although income-based-repayment options have improved their options somewhat. And they make for a dramatic story—as well as lots of moralizing in the comments.

Second, there’s the student who took on debt but didn’t finish a degree. These people often struggle, because their income doesn’t go up much, if at all. In fact, the highest default rates are among those who left school with the smallest debts (< $5000), presumably because they didn’t graduate.