Archive for the ‘just theory’ Category

foucault beyond good and evil

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

democracy is tougher than you think, wealthy ones at least

We often hear that democracy is under threat. But is that true? In 2005, Adam Przeworski wrote an article in Public Choice arguing that *wealthy* democracies are stable but poor ones are not. He starts with the following observation:

No democracy ever fell in a country with a per capita income higher than that of Argentina in 1975, $6055.1 This is a startling fact, given that throughout history about 70 democracies collapsed in poorer countries. In contrast, 35 democracies spent about 1000 years under more developed conditions and not one died.

Developed democracies survived wars, riots, scandals, economic and governmental crises, hell or high water. The probability that democracy survives increases monotonically in per capita income. Between 1951 and 1990, the probability that a democracy would die during any particular year in countries with per capita income under $1000 was 0.1636, which implies that their expected life was about 6 years. Between $1001 and 3000, this probability was 0.0561, for an expected duration of about 18 years. Between $3001 and 6055, the probability was 0.0216, which translates into about 46 years of expected life. And what happens above $6055 we already know: democracy lasts forever.

Wow.

How does one explain this pattern? Przeworski describes a model where elites offer income redistribution plans, people vote, and the elites decide to keep or ditch democracy. The model has a simple feature when you write it out: the wealthier the society, the more pro-democracy equilibria you get.

If true, this model has profound implications of political theory and public policy:

- Economic growth is the bulwark of democracy. Thus, if we really want democracy, we should encourage economic growth.

- Armed conflict probably does not help democracy. Why? Wars tend to destroy economic value and make your country poorer and that increase anti-democracy movements (e.g., Syria and Iraq).

- A lot of people tell you that we should be afraid of outsiders because they will threaten democracy. Not true, at least for wealthy democracies.

This article should be a classic!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

ermakoff book forum 2: of nazis and vichy

The purpose of Ruling Oneself Out is to understand when political groups, or coalitions, literally vote themselves out of power, often with disastrous consequences. Today, I’ll briefly describe the historical cases and tomorrow I’ll discuss the theory Ermakoff uses to explain things.

The first example is the Reichstag’s March 1933 vote to give Hitler broad power. Essentially, the Reichstag abolished democratic controls over the chancellor by giving the chancellor and the cabinet the ability to pass laws with the Reichstag’s approval. Most historians concur that this was the effective end of the Weimar state. It was replaced by a Nazi party state that dispensed with republican institutions.

What is crucial for Ermakoff is that the Nazis won because they had the backing of various Center and right parties, including some who were very suspicious of Hitler. Communists had been banned from the vote and only the Social Democrats voted no.

Ermakoff’s other case is the French government’s vote to give Petain power in 1940. The complete disaster of the French war effort completely destabilized French state, resulting in the withdrawal of the government from Paris, the resignation of the leadership, and the creation of German dominated Vichy France.

In reviewing these two events, Ermakoff wants to criticize a number of explanations offered for the surrender to Nazism. For example, it is often argued that coercion was the main explanatory factor. Non-Nazi parties were justifiably fearful of violence and relented. But Ermakoff notes that this is an incomplete explanation. First, there was actually a fair amount of resistance to Nazi violence. Second, the Center party, which went all in for Hitler, actually was internally split and many seemed able and willing to resist. In France, Ermakoff shows that voting for the Vichy State was not associated with being from an area that would be under German occupation, and thus subject to more violence. Similarly, Ermakoff closely examines the evidence for other theories of abdication, such as the hypothesis that Nazi ideology contaminated its opponents. Tomorrow, I’ll discuss Ermakoff’s alternative theory.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

junior theorist symposium 2016 – submit your paper today!!!

CALL FOR ABSTRACTS

2016 Junior Theorists Symposium

Seattle, WA

August 19, 2016

SUBMISSION DEADLINE: February 22, 2016

We invite submissions of extended abstracts for the 10th Junior Theorists Symposium (JTS), to be held in Seattle, WA on August 19th, 2016, the day before the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association (ASA). The JTS is a one-day conference featuring the work of up-and-coming sociologists, sponsored in part by the Theory Section of the ASA. Since 2005, the conference has brought together early career-stage sociologists who engage in theoretical work, broadly defined.

We are pleased to announce that Mounira Charrad (UT Austin), Ann Mische (Notre Dame), and Tukufu Zuberi (UPenn) will serve as discussants for this year’s symposium. In addition, we are pleased to announce an after-panel on the relationship between theory and method featuring Christopher Bail (Duke), Tey Meadow (Harvard), Ashley Mears (Boston University), and Frederick Wherry (Yale), as well as a talk by 2015 Junior Theorists Award winner Claudio Benzecry (Northwestern).

next week is institutionalism week

I am knee deep in institutionalism. I intend to write a few posts next week laying out where I think we are:

- The split between the institutional work/inhabited institutions crew and institutional logics.

- What was lost in the transition to organizational institutionalism in org studies.

- What “other fields” (e.g., movement research or race) do when they interact with institutionalism.

- Comparison of field theories. Mainly McAdam/Fligstein/Bourdieu vs. John Levi Martin.

As a bonus round, we’re “going full Ermakoff” on Friday.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

some thoughts on institutional logics, in three parts

Last week I was finishing up a volume introduction and it prompted me to catch up on the last couple of years of the institutional logics literature. This gave me some thoughts, and now I can’t sleep, so I’m putting them out there. This is long so it’s broken into three parts. The first two reflect my personal saga with institutional logics. They set up the rest, but you can also skip to the third and final section for the punchline.

book spotlight: thinking through social theory by john levi-martin

John Levi-Martin is one of sociology’s most fertile thinkers. His book, Social Structures, was discussed at length on this blog and The Explanation of Social Action was a well discussed investigation of how social scientists try to approach causality. His new book, Thinking Through Social Theory, is a tour of foundational issues in social science and should be required reading for anyone who wants to understand current debate over the status of social explanation.

Roughly speaking, there is a long standing dispute among scholars about what constitutes a proper explanation of social action. The argument has many facets. For example, there is a dispute over realism, the view that people have fairly direct access to reality which can the be leveraged into causal explanation. There is a related argument about social norms and whether it makes sense to say that a rule “caused” or “forced” someone to act. And of course, there are arguments over the sufficiency of various schools of thought like functionalism, rational choice, and evolutionary theory.

Thinking Through Social Theory is Levi-Martin’s review of these issues. It not only summarizes the landscape, but offers answers drawn from one of his most theoretically rich articles, “What is Field Theory?” It is truly difficult to summarize this tome (e.g., there is multi-page analysis of the “gentlemen open doors for ladies” custom) but I can indicate some high points. First, there is a good review of the issues surrounding realism. And no, he does NOT side with those pesky critical realists. Second, there is an examination of two theories (rational choice and evolutionary psychology) that try to offer “ultimate” accounts of human action. Third, Levi-Martin offers a field theoretic alternative to theories of action that are found in schools as diverse as functionalism, institutionalism, and Swidlerian toolkit theory. The basic intuition is that individuals aren’t carrying around norms, but they are working in fields of action that push people into situations that generate behavioral, or even cognitive, regularities. Sounds like actor-network theory to me, but more meso-level.

So who is this book for? I see a few good audiences. One are social theory grad students. After marching PhD students though the history of soc up the present, it is good to sit back and think about the (lack of?) progress that has been made in building social theory. I also think that the philosophy of social science crowd would enjoy this, as would scholars in cultural sociology who often run into the issue of motivation. Thumbs up.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

the parsons taboo

As readers already know, I am hard at work on a book that reviews contemporary sociology. In writing the book, I ran into two taboos: rational choice and Parsons (ironic, since Parsons was opposed to utilitarianism). The reviewers were very touchy about these two topics. The first makes sense. Sociology has always been allergic to anything “econ-y” or “math-y” from the beginning. I do understand why people might want to expunge a book of rational choice. I still don’t think it’s wise since the profession still has people working in related areas like Granovetter style embeddness research, social capital, Harrison White micro-network hybrid work, and applied game theory. Also, the rational choice tradition (including social capital) is the major link between sociology and the poli sci/economics axis.

The Parsons taboo really surprised me since (a) the book only had a total of about five paragraphs about Parsons, (b) I am definitely not a functionalist and I present it as background for more modern stuff like cultural sociology and institutionalism, and (c) Parsons’ descendants still have big followings, like Jeffrey Alexander and Niklas Luhmann. Also, another weird thing is that the reviewers asked me to incorporate Swidler’s recent work (Talk of Love), a discussion of Poggi’s theory of power and Vaisey’s work, which all explicitly speak of Parsons.

So what is up with this weird allergy to even *mentioning* Parsons? In 2015, are people still fighting the battles of 1975? Here’s my theory. Parsons’ did two things, one bad and one good. The bad thing is that he created a highly visible and rigid orthodoxy, complete with “religious” texts (i.e., his books). That is what the sociologists of the 1970s revolted against and that is what made Parsons the devil in our profession. And I can’t blame people. Reading classic structural functionalist texts is really taxing and frequently unhelpful.

The good thing is that he created, by accident, the kernel of a lot of modern sociology. Inside those big, nasty books, there were a lot of important insights that are now standard. For example, his 1959 ASQ article on organizations made the crucial distinction between the technical and “institutional” components of organizations, a core idea in modern organizational research. The functionalist approach to schools is still a standard reading. The distinction between achieved and ascribed status is “strat 101.” Even his much maligned theory of norm driven action lives on, even if we admit that norms are constructed situationally rather than ex ante.

The “good” and “bad” Parsons explains my situation. You don’t have to be a functionalist to appreciate some of his good ideas, nor do you need to be a hard core follower to understand the historical importance of Parsons. For example, you simply can’t understand why Swidler’s (1983) toolkit argument was such a big deal unless you understand how Parsons’ theory of norms and his interpretation of the Protestant Ethic was dominant at the time. The Swidler critique set the agenda for cultural sociology for decades. So you need to address Parsons and point out the contribution. If you do that, however, people get angry because they remember (or their advisers told them) about the bad Parsons.

This also helps explain when and where you can get away with it. If the whole text is about critiquing work like Parsons and developing alternatives (e.g., Swidler or Vaisey), you can do it. If you are very senior scholar who is writing “big think” work (e.g. Gianfranco Poggi), you can do it. But not a synthetic and pedagogical overview – people will think that even including him (or the rational choicers) is a horrendous rear-guard action that puts discredited work back into the canon.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street

book naming contest winner….

The accounting firm of Weber, Durkheim and Simmel has carefully counted the votes from last week’s book naming contest. The winner will get $20 (via PayPal or ASA handoff) or one my sociology books (From Black Power or Party in the Street) or ten copies of Grad Skool Rulz mailed to friends. The winner will also be given a place of honor in the acknowledgements should the book ever get published. Drum roll, please…

junior theorists symposium 2015

As usual, the Junior Theorists Symposium has an amazing line up. Day before the ASA. Check it out!

Junior Theorists Symposium

University of Chicago

Social Sciences Room 122

the risky sex game paper – professional lessons

My first ever journal publication was an article called “A Game Theoretic Model of Sexually Transmitted Disease Epidemics.” It appeared in the journal Rationality and Society in 2002. As the title suggests, the goal of the paper is to model network diffusion using agents that play games with each other. Specifically, let’s assume people want to have sex with each other. The catch is that some people have HIV (or another disease) and some don’t. Further, let’s assume that people will estimate the probability that the partner has HIV based on the type of sex they offer and the current disease prevalence. In other words, offering unprotected sex in a world without STD’s is interpreted way differently than the same offer in a world where lots of people have infections. In this post, I want to briefly discuss what I learned by writing this paper. Tomorrow, I will talk about the small, but interesting, literature in biology and health economics that has referenced this paper.

Lesson #1: Interdisciplinary work doesn’t have to be garbage. The paper uses ideas from at least three different scholarly areas – game theory/economics; social networks/sociology; and probability theory/epidemiology. Orgtheory readers will be familiar with game theory and networks. But the paper uses a cool idea from probability theory called “pairs at a party model” – to model diffusion, you draw people from a pool and match them. I added these ideas: people can only be paired with people they know (the network) and then to decide if they have intercourse, they play a signalling game (game theory).

Lesson #2: Working with your buddies is amazing. My co-author on the project was Kirby Schroeder, who now works in the private sector. We developed the idea by thinking about his personal experience. Gay men often encounter the signaling problem – say you meet a partner and he offers unprotected sex. What does that suggest? We then joined forces to write the paper. Great experience.

Lesson #3: People can get angry at your research. During conferences and peer review, we experienced great hostility because we relied on the literature showing that sometimes, people don’t tell partners about STD’s and thus put them at risk. One woman, who claimed to be a researcher from Massachusetts General Hospital, literally yelled at me during an ASA session. The paper got rejected from Journal of Sex Research, after an R&R, because one reviewer got very upset and claimed that were defaming gay people and that “you don’t know what love means.” Do any of us, really?

Lesson #4: Long term matters. The paper was published in Rationality and Society and then quickly disappeared. But it had an interesting after life. It got an ASA grad student paper award from the Math Soc section. During the first couple of years on the job, it was the only journal publication on the CV, which saved me from complete embarrassment. In one review of my work, it was the *only* paper that the committee actually liked. Later, a member of the RWJ selection committee said that the paper was the only reason that they invited me for an interview, because it showed a genuine commitment to health research. Even better, starting around 2010, researchers rediscovered the paper and now it is part of a larger literature on sexual risk spanning biology, economics, and health. So even though it didn’t have an immediate impact, a well written paper can pay off in ways you might not expect.

Tomorrow: What people get from the Risky Sex Game paper.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

theory bleg: swidler 1.0 vs. 2.0

Help me deal with Reviewer 2, a most helpful person: Best source to read where Swidler discusses her recent views vs. Swidler circa 86?

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

states, states, and more states – a guest blog post by nick rowland

Nicholas Rowland is an associate professor of sociology at Penn State – Altoona. He is a sociologist of science and an Indiana alumnus. In this guest post, he asks for your help in exploring how social scientists imagine the state.

Greetings Orgtheory community,

I write to ask for help, help in hunting-down states. I am in the middle of compiling a list of different state concepts from all over academia. By “state concepts” (specifically plural) I am referring of concepts that appear to be crafted according to the formula “[select key term] state” wherein “[s]tate activity related to [select key term] becomes the definition of the self-referential term” (2015). Many of you are doubtlessly familiar with these sorts of concepts, for example, Adams’ “spectacular state” or Karl’s “petro state” of Guss’s “festive state” or Geertz’s “theater state” and so on. While some of these terms are esoteric and perhaps only used once or only by one scholar, others – such as “modern state,” “bureaucratic state” or “administrative state” – are so commonplace they almost appear to have no progenitor at all.

If you are familiar with concepts not featured below, please do leave a quick comment with the name of the concept and, if possible, some idea of where it comes from – even a vague idea of its origins helps. So far, this is the list of state concepts, and “thank you in advance” to those who offer to help.

[Ed. – It gets real statey and fun below this page break… you’ve been warned.]

rational choice bleg

Question for the weekend: I am searching for an example of a theory or empirical work that combines rational choice theory with some other style of social theory. A few candidates:

- Analytical Marxism

- Michael Chwe’s theory of ritual and interaction

- A friend recommended Anthony Giddens’ structuration, as it has goal oriented actors who behave in endogenously created social structures

Other suggestions? Bonuses for recent work, work that is empirical, or accessible to general educated readers.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

the fabio test, or how to judge “social theory”

I am often asked, why do I relentlessly criticize obscure theory yet find a place in my heart for Foucault? The answer is simple. I judge rhetoric separately than intellectual content. I think it is possible, and often helpful, to separate how an idea is discussed from the idea itself. How do I do it? Simple – take some tangly-talk and then translate it into the simplest language possible. If the idea is still interesting after decontamination, I give a thumbs up. If I get a platitude, or worse, thumbs down.

So let’s get back to Foucault. What happens if we drop Foucault in solvent? I’d say that some of Foucault’s biggest insights are:

- Discipline and Punish: Western society has moved from punishing people through physical force to having people regulate themselves.

- History of Sexuality: Sexuality varies greatly over time and is more diverse than people expect. Then, people created a science to make sexuality intelligible to intellectuals.

- Archaeology of Knowledge/The Order of Things: There is an order, or structure, to how people understand things and we can see that through a close reading of intellectuals of various eras.

These hypotheses can be debated, but, at the very least, they are hypotheses that make sense and can be assessed. There are hypothesis which are falsifiable (e.g., maybe Foucault’s description of the history of corporal punishment is simply wrong). My beef with much theory is that when you translate and simplify, you either get platitudes, obvious points, extremely wrong points, or a modest point dressed up in confusing verbiage.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street!!

social theorists: i challenge you!!!

Last week, we discussed Omar’s essay on the end of the “theorist” in sociology. I share the concern of many people who don’t use the label of “theorists.” Theory is often presented in a way that obscure and appears disconnected from the core concerns of sociologists. In the comments, Omar responded to me, and others, by noting that one legacy of Parsons was the creation of the “theorist.” In other words, now that we have theorists, we need to give them something useful to do.

Here is my suggestion: Take a field that is empirically deep and important, but under developed theoretically. Then, work on a synthesis that ties it together and integrates it with current “theory.” Here are my candidates:

- Demography

- Public opinion

- Health

- Criminology

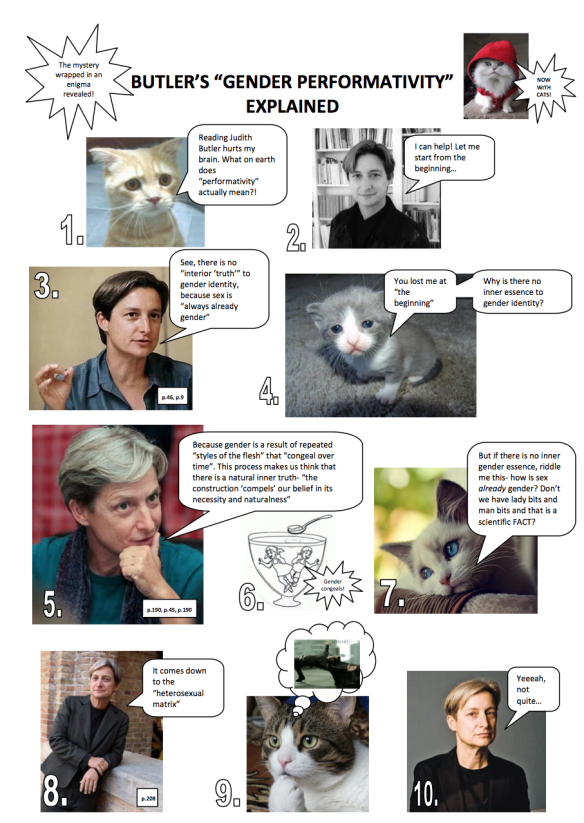

In each case, the topic is hugely important and well developed but even practitioners admit that it is fairly atheoretical. They need your help, theorists. So put that Judith Butler back on the shelf and return that Zizek to the library and show me what you can do.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/F

junior theorist symposium

Announcement from one of the hippest groups in sociology:

CALL FOR ABSTRACTS

2015 Junior Theorists Symposium

Chicago, IL

August 21, 2015

SUBMISSION DEADLINE: FEBRUARY 13, 2015

We invite submissions for extended abstracts for the 9th Junior Theorists Symposium (JTS), to be held in Chicago, IL on August 21st, 2015, the day before the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association (ASA). The JTS is a one-day conference featuring the work of up-and-coming theorists, sponsored in part by the Theory Section of the ASA. Since 2005, the conference has brought together early career-stage sociologists who engage in theoretical work.

We are pleased to announce that Patricia Hill Collins (University of Maryland), Gary Alan Fine (Northwestern University), and George Steinmetz (University of Michigan) will serve as discussants for this year’s symposium.

In addition, we are pleased to announce an after-panel on “abstraction” featuring Kieran Healy (Duke), Virag Molnar (The New School), Andrew Perrin (UNC-Chapel Hill), and Kristen Schilt (University of Chicago). The panel will examine theory-making as a process of abstraction, focusing on the particular challenge of reconciling abstract “theory” with the concrete complexities of human embodiment and the specificity of historical events.

We invite all ABD graduate students, postdocs, and assistant professors who received their PhDs from 2011 onwards to submit a three-page précis (800-1000 words). The précis should include the key theoretical contribution of the paper and a general outline of the argument. Be sure also to include (i) a paper title, (ii) author’s name, title and contact information, and (iii) three or more descriptive keywords. As in previous years, in order to encourage a wide range of submissions we do not have a pre-specified theme for the conference. Instead, papers will be grouped into sessions based on emergent themes and discussants’ areas of interest and expertise.

Please send submissions to the organizers, Hillary Angelo (New York University) and Ellis Monk (University of Chicago), at juniortheorists@gmail.com with the phrase “JTS submission” in the subject line. The deadline is February 13, 2014. We will extend up to 12 invitations to present by March 13. Please plan to share a full paper by July 27, 2015.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz/From Black Power

of dead sociologies

I am now old enough that I have seen three traditions in American sociology die. In describing them, I am not necessarily saying that I don’t like them. In fact, I am a published practitioner in one of them. Rather, these traditions have not been able to reproduce themselves at the core of the profession. They may be popular in other fields, but not in soc:

- Functionalism/neo-functionalism

- Postmodernism

- Rational choice

Each promised a lot and had a moment in American sociology. Munch, Alexander, and others led the charge on neo-functionalism in the 1990s, and Luhmann has a following. Rational choice still has notable adherents, like Doug Heckathorn at Cornell or Richard Breen at Yale. And the AJS and ASR had their share of articles discussing postmodernism (here, for example). But still, it’s hard to say that these traditions aren’t dormant in American sociology. Few students, few placements.

The question is whether there is any commonality. Is American sociology resistant to certain types of theory? If these three cases indicate a deeper process, then I’d make the following guesses:

- “Strong assumptions” – American sociologists don’t like models with what appear to be overly strong assumptions. Rational choice models have smart actors; postmodernism has overly complex actors; and the various functionalisms had actors that were hyper sensitive to social norms and communities were overly structured.

- “High tech” – With the exception of applied statistics, American sociologists don’t like fancy things. The AGIL system in functionalism; math for RCT; European philosophy/social theory for post-modernism.

So the ideal theory would be one with weak assumptions and requires little machinery. Many of the dominant theories these days seem to fit this: institutionalism/field theory; intersectionality theory; theories of racial privilege; etc. Network theory rests on simple, but weak, assumptions and uses only stats.

It is unclear to me if this is a good or bad state of affairs. However, if you think it’s bad, then you have a real problem. The most obvious way to change it is to recruit different kinds of people into the profession who like demanding theory or high tech tools. That seems like a tall order given our undergraduate audience, which is the major talent pool for the profession.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz/From Black Power

thinning out orgtheory

Recently, Elizabeth and Brayden have drawn attention to the institutional position of organizational sociology. Three pertinent facts:

- A lot of organizational sociologists have moved to b-schools.

- The major orgtheory/b-school journal, ASQ, rarely publishes people in sociology programs.*

- The dominance of institutional theory

When I look at these trends, I see two things. One, orgtheory has market value. A low budget discipline like sociology simply won’t retain people. Two, I think there is a “thinning” that is occurring in orgtheory. While orgtheory remains vibrant, it is now, in sociology, a field that has jettisoned much of its heritage. Sociologists have gravitated toward big structural theories, like institutionalism, networks, and ecology (the big three, as Heather might say). But what happened to the rest? Why don’t sociologists care about Carnegie school theory? Why have people stopped working on Blau style middle level theory? Human relations?

The answer is not clear to me. One culprit might be the journal system. To succeed in sociology at the higher levels, you need fast publication in two or three journals and it’s probably easier to just work on well established variables/processes (diffusion/density/networks). I certainly did that and I freely admit that I’d be unemployed if I tried to hatch new variables. Second, there might simply be a new division of labor in academia. The “sociology of organizations” now simply means structural analysis. An “b-school orgtheory” means other features of orgs, like performance, that sociologists care less about.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: From Black Power/Grad Skool Rulz

* That didn’t have to be the case, Don.

go > chess

A Wired article explains how artificial intelligence has now been able to crack the game of Go and why it’s harder than chess. From the write up:

Good opens the article by suggesting that Go is inherently superior to all other strategy games, an opinion shared by pretty much every Go player I’ve met. “There is chess in the western world, but Go is incomparably more subtle and intellectual,” says South Korean Lee Sedol, perhaps the greatest living Go player and one of a handful who make over seven figures a year in prize money. Subtlety, of course, is subjective. But the fact is that of all the world’s deterministic perfect information games — tic-tac-toe, chess, checkers, Othello, xiangqi, shogi — Go is the only one in which computers don’t stand a chance against humans.

This is not for lack of trying on the part of programmers, who have worked on Go alongside chess for the last fifty years, with substantially less success. The first chess programs were written in the early fifties, one by Turing himself. By the 1970s, they were quite good. But as late as 1962, despite the game’s popularity among programmers, only two people had succeeded at publishing Go programs, neither of which was implemented or tested against humans.

a rant on ant

Over at Scatterplot, Andy Perrin has a nice post pointing to a recent talk by Rodney Benson on actor-network theory and what Benson calls “the new descriptivism” in political communications. Benson argues that ANT is taking people away from institutional/field-theoretic causal explanation of what’s going on in the world and toward interesting but ultimately meaningless description. He also critiques ANT’s assumption that world is largely unsettled, with temporary stability as the development that must be explained.

At the end of the talk, Benson points to a couple of ways that institutional/field theory and ANT might “play nicely” together. ANT might be useful for analyzing the less-structured spaces between fields. And it helps draw attention toward the role of technologies and the material world in shaping social life. Benson seems less convinced that it makes sense to talk nonhumans as having agency; I like Edwin Sayes’ argument for at least a modest version of this claim.

I toyed with the possibility of reconciling institutionalism and ANT in an article on the creation of the Bayh-Dole Act a few years back. But really, the ontological assumptions of ANT just don’t line up with an institutionalist approach to causality. Institutionalism starts with fairly tidy individual and collective actors — people, organizations, professional groups. Even messy social movements are treated as well-enough-defined to have effects on laws or corporate behavior. The whole point of ANT is to destabilize such analyses.

That said, I think institutionalists can fruitfully borrow from ANT in ways that Latour would not approve of, just as they have used Bourdieu productively without adopting his whole apparatus. In particular, the insights of ANT can get us at least two things:

1) It not only increases our attention to the role of technologies in shaping organizational and field-level outcomes, but ANT makes us pay attention to variation in the stability of those technologies. It is simply not possible to fully accounting for the mortgage crisis, for example, without understanding what securitization is; how tranching restructured, redistributed and sometimes hid risk; how it was stabilized more or less durably in particular times and places; and so on.

You can’t just treat “securitization” as a unitary explanatory factor. You need to think about the specific configuration of rules, organizational practices, technologies, evaluation cultures and so on that hold “securitization” together more or less stably in a specific time and place. Sure, technologies are sometimes stable enough to treat as unified and causal—for example, a widely used indicator like GDP, or a standardized technology like a new drug. But thinking about this as a question of degree improves explanatory capacity.

An example from my own current work: VSL, the value of a statistical life. Calculations of VSL are critical to cost-benefit analyses that justify regulatory decisions. They inform questions of environmental justice, of choice of medical treatment, of worker safety guidelines. All sorts of political assumptions — for example, that the lives of people in poor countries are worth less than people in rich ones — are baked into them. There is no uniform federal standard for calculating VSL — it varies widely across agencies. ANT sensitizes us not only to the importance of such technologies, but to their semi-stable nature—reasonably persistent within a single agency, but evolving over time and different across agencies.

2) Second, ANT can help institutionalists deal better with evolving actors and partial institutionalization. For example, I’m interested in how economists became more important to U.S. policymaking over a few decades. The problem is that while you can define “economist” as “person with a PhD in economics,” what it means to be an economist changes over time, and differs across subfields, and is fuzzy around the borders.

I do think it’s meaningful to talk about “economists” becoming more influential, particularly because the production of PhDs happens in a fairly stable set of organizational locations. But you can’t just treat growth theorists of the 1960s and cost-benefit analysts from the 1980s and the people creating the FCC spectrum auctions in the 1990s as a unitary actor; you need ways to handle variety and evolution without losing sight of the larger category. And you need to understand not only how people called “economists” enter government, but also how people with other kinds of training start to reason a little more like economists.

Drawing from ANT helps me think about how economists and their intellectual tools gain a more-or-less durable position in policymaking: by establishing institutional positions for themselves, by circulating a style of reasoning (especially through law and public policy schools), and by establishing policy devices (like VSL). (See also my recent SER piece with Dan Hirschman.) Once these things have been accomplished, then economics is able to have effects on policy (that’s the second half of the book). While the language I use still sounds pretty institutionalist—although I find myself using the term “stabilized” more than I used to—it is definitely informed by ANT’s attention to the work it takes to make social arrangements last. Thus I end up with a very different story from, for example, Fligstein & McAdam’s about how skilled actors impose a new conception of a field — although new conceptions are indeed imposed.

I don’t have a lot of interest in fully adopting ANT as a methodology, and I don’t think the social always needs to be reassembled. The ANT insights also lend themselves better to qualitative, historical explanation than to quantitative hypothesis testing. But all in all, although I remain an institutionalist, I think my work is better for its engagement with ANT.

show me the benjamins!!!

I am not well read in Benjamin’s ouevre, but I’ve always been semi-impressed. Moments of brilliance, but I couldn’t quite wrap my head around the big contribution. Well, Walter Laquer makes the argument that Benjamin is an over-rated thing. From the Mosaic:

Yes, his ideas (as in his best-known essay, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”) were often original, and there were flashes of genius. But in what precisely did his genius consist? Had he produced a new philosophy of history, proposed a fundamentally new approach to our understanding of 19th-century European culture, his main area of concern, or revolutionized our thinking about modernity? The answers I received weren’t persuasive then, and the answers provided in the vast secondary literature of the last decades have done no better.

And:

Wherein lay its originality? The figure of the flâneur had been “discovered” earlier in the novels of Honoré de Balzac and others, and the main themes of Baudelaire’s poems had been studied even by German academics, some of whom had offered analyses not dissimilar to Benjamin’s. Were the Parisian arcades, with or without Baudelaire, the right starting point for a new understanding of modernity? Even the most detailed Benjamin biography, by the distinguished French professor Jean Michel Palmier, reaches no satisfying conclusion on this point. (Palmier’s mammoth book, almost 1,400 pages long, remains, like Benjamin’s work, unfinished—which is a comment in itself.)

Defenders – show me the Benjamins!

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: From Black Power/Grad Skool Rulz

the real philosophy of social science puzzle

There is an intrinsic interest in the philosophy of social science. Ideally, we all want well motivated and logical explanations for how we should do our professional work. However, there is usually one question that you don’t hear much about – why does scholarship seem to progress in the absence of a well motivated philosophy? In other words, doctors probably have a bad philosophy of science, but I don’t see philosophers refusing the services of their physicians.

I don’t have an answer to this, I’ve only started to think about this issue. But I raise it in the shadow of our debate over critical realism and the earlier debate over post-modernism. The claim of some supporters is that social scientists really need a new theory of social science (e.g., critical realism) because social scientists rely on a flawed positivist theory. It may be true that positivist social science is wrong and that we should adopt a newer theory. This view does not take into account two issues: (a) The cost of adopting a new theory is steep. If Kieran can’t quite get critical theory after reading it for 18 months, then I sure won’t get it. (b) A new social science that proceeds along new rules of engagement may not generate enough differences to make it worthwhile. For example, now that Phil Gorski has adopted critical realism, how would his book, The Disciplinary Revolution, be written any differently? Not clear to me since a lot of what Gorski does in that book is apply a specific theoretical lens in reading various developments in state formation. He might sprinkle a discussion of “multiple levels of causation” at the top but then he’d probably proceed to make similar arguments with similar data.

The ultimate puzzle, though, is in areas that seem to make progress even when practitioners work with a bad philosophy. This suggests that the demand for better foundations simply isn’t important for generating knowledge. Another datum is that advances in science, or social science, rarely require entirely new foundations. Take sociology. I don’t need to adopt anything new to, say, appreciate Swidler’s attack on functionalism. And I seem to be able to understand most feminist sociology by using meat and potatoes positivism. The bottom line is that, at the very least, there needs to be an explanation for the ubiquitous disjuncture between foundations and practice.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: From Black Power/Grad Skool Rulz

the end of institutionalism as have known it

Around 2004 or so, I felt that we were “done” with institutionalism as it was developed from Stinchcombe (1965) to Fligstein (2000). My view was that once you focused on the organizational environment and produced a zillion diffusion studies, there were only so many extra topics to deal with. For example, you could propose a strong coupling argument (DiMaggio and Powell 1983) or weak coupling argument (Weick 1976 or Meyer and Rowan 1977). Then maybe you could do innovation within a field (DiMaggio’s institutional entrepreneur argument) or how people exploited fields (Fligstein’s social skill argument). Finally, starting with Clemens (1999), and then Armstrong (2004), then Bartley (2006), and then the work of the orgs/movement crowd (including Brayden and myself) you got into contention. So what else was left?

Well, it turns out there are two major moves that force you in a new direction. One might be called the “aspects of fields” program – which means that you study some element of an organizational field in depth and really analyze the living day lights out of it. For example, the Ocasio/Thornoton/Lounsbury stuff on institutional logics is an example. Another example is the new stuff by Suddaby and Lawrence on institutional work, which includes some of my work on power building in organizations.

The other program is the Fligstein/McAdam Theory of Fields, which essentially marries “social skill” era Fligstein with the incumbent-challenger dynamics that was highlighted in The Dynamics of Contention book. In other words, you rub the Orange Bible and DoC together and hope the child is attractive.

The purpose of this post is not to evaluate these programs. That’ll come later, and there will some special summer action concerning ToF. But here, I am just mapping out institutional theory as it stands these days. The “aspects of institutionalism” program is clearly a deepening and refinement of the theory that emerged in early post-Parsons sociology. On Facebook, I asserted that ToF was our “new new institutionalism,” and there was push back. I think my position is that, as far as genealogy and conent is concerened, ToF is a merger of two separate ideas.

As far as the discipline is concerned, management likes the aspects program because it is relatively easy to stick to firm level dynamics. Studies of executives, or regulations, or what have you can be pegged to “institutional X” theory. In contrast, sociologists like conflict a bit more and movements, so ToF will prove popular. If nothing else, it provides a simple and intuitive vocabulary for the types of social processes that contemporary macro-sociologists like to talk about.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: From Black Power/Grad Skool Rulz

anarchism week at orgtheory

What the heck, let’s do anarchism week. Let’s start with the following conversation I had at the end of my social theory class a few semesters ago. A student approached me and asked why I didn’t teach anarchism in the course. There’s a few good reasons, but not so strong that you couldn’t include it if you really wanted to.

First, the goal of my social theory class is to have people read original texts written by seminal social thinkers. This doubles as a sort of Western civ (since IU doesn’t require it) and people need to understand the core arguments of sociology. So we hit the “classics,” the interactionists, feminists, French theory,* and a little evolutionary psych. The course also needs to prepare a handful of students who will continue in soc, poli sci, or other fields at the graduate level.

Second, I teach things that really drive discussion in contemporary sociology, which means that that many topics, including those dear to my heart, must get cut. Since there are very few anarchist sociologists, or research that uses an anarchist perspective, it means that it simply isn’t a priority.

But that doesn’t mean that anarchism isn’t a real social theory or that it should be actively excluded. In contrast, there’s now a body of anarchist themed social writings, mainly in fields other than sociology. For example, anthropologist David Graeber’s writings should count. James Scott, the political scientist, has written about statelessness at length. There are the classic anarchists, like Prodhoun, and feminist anarchists like Emma Goldman. You have right wing anarchists like economist Murray Rothbard or philosopher Michael Huemer. Then you have empirical studies of statelessness like Pete Leeson’s pirate book.

In other words, you have more than enough material and it’s high quality material. But it’s definitely not central to sociology (yet?), so you don’t feel guilty cutting it. But the social theory course isn’t set in stone. I am already tiring of French theory and other topics, so it may be time to rotate some new material in.

Fight the Power … with these books!: From Black Power/Grad Skool Rulz

* Remember, I don’t teach postmodernism anymore.

junior theorists symposium 2014

From my guy in Ann Arbor:

2014 Junior Theorists Symposium

Berkeley, CA

15 August 2014

SUBMISSION DEADLINE: 15 FEBRUARY 2014

We invite submissions for extended abstracts for the 8th Junior Theorists Symposium (JTS), to be held in Berkeley, CA on August 15th, 2014, the day before the annual meeting of the American Sociological Association (ASA). The JTS is a one-day conference featuring the work of up-and-coming theorists, sponsored in part by the Theory Section of the ASA. Since 2005, the conference has brought together early career-stage sociologists who engage in theoretical work.

We are pleased to announce that Marion Fourcade (University of California – Berkeley), Saskia Sassen (Columbia University), and George Steinmetz (University of Michigan) will serve as discussants for this year’s symposium.

In addition, we are pleased to announce an after-panel on “The Boundaries of Theory” featuring Stefan Bargheer (UCLA), Claudio Benzecry (University of Connecticut), Margaret Frye (Harvard University), Julian Go (Boston University), and Rhacel Parreñas (USC) . The panel will examine such questions as what comprises sociological theory, and what differentiates “empirical” from “theoretical” work.

We invite all ABD graduate students, postdocs, and assistant professors who received their PhDs from 2010 onwards to submit a three-page précis (800-1000 words). The précis should include the key theoretical contribution of the paper and a general outline of the argument. Be sure also to include (i) a paper title, (ii) author’s name, title and contact information, and (iii) three or more descriptive keywords. As in previous years, in order to encourage a wide range of submissions, we do not have a pre-specified theme for the conference. Instead, papers will be grouped into sessions based on emergent themes.

Please send submissions to the organizers, Daniel Hirschman (University of Michigan) and Jordanna Matlon (Institute for Advanced Study in Toulouse), at juniortheorists@gmail.com with the phrase “JTS submission” in the subject line. The deadline is February 15, 2014. We will extend up to 12 invitations to present by March 15. Please plan to share a full paper by July 21, 2014.

Need advice? Buy this book!!: From Black Power/Grad Skool Rulz

More words on critical realism: Getting clear on the basics

One thing that I found dissatisfying about our earlier “discussion” on CR is that it ultimately left the task of actually getting clear on what CR “is” unfinished (or bungled). Chris tried to provide a “bulletpoint” summary in one of the out of control comment threads, but his quick attempt at exposition mixed together two things that I think should be kept separate (what I call high level principles from substantively important derivations from those principles). This post tries to follow Chris Smith’s (sound advice) that ” We’ll all do better by focusing on important matters of intellectual substance, and put the others to rest.”

The task of getting clear on the nature of CR is particularly relevant for people who haven’t already formed strong opinions on CR and who are just curious about what it is. My argument here is that neither proponents nor critics do a good job of just telling people what CR is in its most basic form. The reason for this has to do with precisely the complex nature of CR as an ontology, epistemology, theory of science, and (most importantly) a set of interrelated theses about the natural, social, cultural, mental, world that are derived from applying the high level philosophical commitments to concrete problems. My argument is that CR will continue to draw incoherent reactions and counter-reactions (by both proponents and opponents) unless these aspects are disaggregated, and we get clear on what exactly we are disagreeing about. One of these incoherent reactions is that CR is both a “giant” package of meta-theoretical commitments and that CR is actually a fairly “minimalist” set of principles the reasonable nature of which would only be denied by the certifiably insane.

In particular it is important to separate the high level “core” commitments from all the substantive derivations, because it is possible to accept the core commitments and disagree with the derivations. In essence, a lot of stuff (actually most of the stuff) that gets called “CR” consists of a particular theorist’s application of the high level principles to a given problem. For instance, one can apply (as did Bhaskar in the “original” contributions) the high level ontology to derive a (general) theory of science. One can (as Bhaskar also did) use the general theory of science to derive a local theory (both descriptive and normative) of social science (via the undemonstrable assumption that social science is just like other sciences). And the same can be done for pretty much any other topic: I can use CR to derive a general theory of social structures, or human action, or culture, or the person, or whatever. Once again, the cautionary point above stands: I can vehemently disagree with all the special theories, while still agreeing with the high level CR principles. In other words I can disagree with the conclusion while agreeing with the high-level premises because I believe that you can’t get where you want to go from where you start. This may happen because let’s say, I can see the CR theorist engaging in all sorts of reasoning fallacies (begging the question, arguing against straw men, helping him or herself to undemonstrable but substantively important sub-theses, and so on) to get from the high level principles to the particular theory of (fill in the blank: the person, social structure, social mechanisms, human action, culture, and so on).

This is also I believe the best way to separate the “controversial” from the “uncontroversial” aspects of CR, and to make sense of why CR appears to be both trivial and controversial at the same time. In my view the high level principles are absolutely uncontroversial. It is the deployment of these principles to derive substantively meaningful special theories with strong and substantively important implications that results in controversial (because not necessarily coherent or valid at the level of reasoning) theories.

The High Level Basics.-

One thing that is seldom noted by either proponents or critics of CR is that the fundamental high level theses are actually pretty simple and in fact fairly uncontroversial. These only become “controversial” when counterposed to nutty epistemologies or theories of science that nobody holds or really believes (e.g. so-called “positivism”, radical social constructionism, or whatever). I argued against this way of introducing CR precisely because it confounds the level at which CR actually becomes controversial.

So what are these theses? As repeatedly pointed to by both Phil and Chris in the ridiculously long comment thread, and as ritualistically introduced by most CR writers in social theory (e.g. Dave Elder-Vass), these are simply a non-reductionist “realism” coupled to a non-reductionist, neo-Aristotelian ontology.

The non-reductionist realism part is usually the one that is much ballyhooed by proponents of CR, but in my view, this is actually the least interesting (and least distinctive) part of CR in relation to other options. In fact, if this was all that CR offered, there would be no reason to consider it any further. So the famous empirical/actual/real (EAR) triad is not really a particularly meaningful signature of CR. The only interesting high-level point that CR makes at this level is the “thou shall not reduce the real to the actual, or worse, to the empirical.” Essentially: the world throws surprises at you because it is not reducible to what you know, and is not reducible to what happens (or has happened or will happen). I don’t think that this is particularly interesting because no reasonable person will disagree with these premises. Yes, there are people that seem to say something different, but once you sit them down for 10 minutes and explain things to them, they would agree that the real is not reducible to our conceptions or our experiences of reality. Even the seemingly more controversial point (that reality is not reducible to the actual) is actually (pun intended) not that controversial. In this sense CR is just a vanilla form of realism.

When we consider the CR conception of ontology then things get more interesting. Most CR people propose an essentially neo-Aristotelian conception of the structure of world as composed of entities endowed with inherent causal powers. This conception links to the EAR distinction in the following sense: The real causal powers of an entity endow it with a dispositional set of tendencies or propensities to generate actual events in the world; these actual events may or may not be empirically observable. The causal powers of an entity are real in the sense that these powers and propensities exist even if they are never actualized or observed by anyone. To use the standard trite example, the causal power to break a window is a dispositional property of a rock; this property is real in these that it is there whether it is ever actualized (an actual window breaking with a rock event happens in the world), and whether anybody ever observes this event.

Reality then, is just such a collection of entities endowed with causal powers that come from their inherent nature. The nature of entities is not an unanalyzable monad but is itself the (“emergent” in the sense outlined below) result of the powers and dispositions of the lower level constituents of that entity suitably organized in the right configuration. What in earlier conceptions of science are called “laws of nature” happen to be simply observed events generated by the actualization of a mechanism, whereby a “mechanism” is simply a regular, coherently organized, collection of entities endowed inherent causal powers acting upon one another in a predictable fashion. Scientists isolate the mechanism when they are able to manipulate the organization of the entities in question so that the event is actualized with predictable regularity; these events are then linked to an observational system to generate the so-called phenomenological or empirical regularities (“the laws”) that formed the core of traditional (Hempelian) conceptions of science.

The laws thus result from the regular operation of “nomological machines” (in Cartwright’s sense). The CR point is thus that the phenomenological “laws” are secondary, because they are just the effect produced by hooking together a real mechanism to produce (potentially) observable events in a regular way. So the CR people would say that Hacking’s aphorism “if you can spray them they are real” is made sense of by the unobservable stuff that you can spray is an entity endowed with the causal power capable of generating observable phenomena when isolated as part of an actualized mechanism. The observability thing is secondary, because the powers are there whether you can observe the entity or not. That’s the CR “theory of science.”

The key to the CR ontology is that the nature of entities is understood using a “layered” ontological picture in which entities are understood as essentially wholes made of parts organized according to a given configuration (a system of relations). These “parts” are themselves other entities which may be decomposable into further parts (lower level entities organized in a system of relations and so on). Causal powers emerge at different levels and are not reducible to the causal powers of some “fundamental” level. Thus, CR proposes a non-reductionist, “layered” ontology, with emergent causal powers at each level.

This emergence is “ontological” and not “epistemic” in the sense that the causal powers at each level are “real” in the standard CR sense: they are not reducible to their actual manifestations nor are these “emergent” properties simply an epistemic gloss that we throw into the world because of our cognitive limitations. Thus, CR is an ontological democracy which retains the part-whole mereology of standard realist accounts, but rejects the reductionist implication that the structure of the world bottoms out at some fundamental level of reality where the really real causal powers can be found (and with higher level causal powers simply being a derivative shadow of the fundamental ones).

Getting controversial.-

Now you can see things getting interesting, because we have a stronger set of position takings. Note that from our initial vanilla realism, and our seemingly innocuous EAR distinction, along with a meatier conceptualization of entities as organized wholes endowed with powers and propensitities, we are now living in a world composed of a panoply of real entities at different levels of analysis, endowed with (non-reducible) real causal powers at each level. The key proposition that is beginning to generate premises that we can actually have arguments about is of course the premise of ontological emergence. I argue that this premise not a CR requirement. For instance, why can’t I be a reductionist critical realist? (RCR) Essentially, RCR accepts the EAR distinction, but privileges a fundamental level; this fundamental level may ultimately figure in our theoretical conceptions of reality but it is the bedrock upon which all actual and empirical events stand. In other words, the only true “mechanisms” that I accept are the ones composed of entities at the most fundamental level of reality, which may or may not ever be uncovered. I don’t seriously intend to defend this position, but just bring it up as an attempt to show that CR hooks together a lot of things that are logically independent (emergentist ontology, Aristotelian conception of entities, part-whole mereology, with a “causal powers” view of causation, among others).

In any case, my argument is that most of the substantively interesting CR theses do not emerge (pun intended) from the Bhaskarian theory or science, or the account of causation, or the EAR distinction. They emerge from hooking together (ontological) emergentism and an Aristotelian conceptions of entities and dispositional causal powers. For emergentism is what generates the (controversial) explosion of real entities in CR writing. Not only that, emergentism is the only calling card that CR writers have to provide what Dave Elder-Vass has called a “regional ontology” for the social sciences, that does not resolve into just repeating the boring EAR distinction or the (increasingly uncontroversial) “theory of science” that Bhaskar developed in A Realist Theory of Science and The Possibility of Naturalism.

How to be a (controversial) Critical Realist in two easy steps.-

So now that we have that covered, it is easy to show how to produce a “controversial” CR argument. First, pick a mereology. Meaning, pick some entities to serve as the parts, preferably entities that themselves do not have a controversial status (most people would agree that the entities exist, form coherent wholes, have natures, and so on), and pick a more controversially coherent whole that these parts could conceivably be the parts of. Then argue that the parts do indeed form such a whole via the ontological emergence postulate. Note that the postulate allows you to fudge on this point, because you do not actually have to specify the mechanism via which this ontological emergence relation is actualized (you can argue that that is the job of empirical science and so on). Then hooking the CR notion of causal powers and the EAR distinction and the postulate of ontological democracy of all entities argue that this whole is now a super-addition to the usual vanilla reality. That is, the new emergent entity is real in the same sense that other things (apples, rocks, leptons, cells) are real. It has a inherent nature, a set of dispositions to generate actual events, and most importantly it has causal powers. The powers of this new emergent entity may be manifested at its own level (by affecting same-level entities), or they may be exhibited by the constraining power of that entity upon the lower level constituent entities (the postulate of “downward causation”). For instance, (to mention one thing that could actually be of interest to readers of this blog), Dave Elder-Vass has provided an account of the reality of “organizations” (and the non-reducibility of organizational action to individual action) using just this CR recipe.

Now we have the materials to make some people (justifiably) discomfited about a substantive CR claim (or at least motivated to write a critical paper). For if you look at most of the contributions of CR to various issues they resolve themselves to just the steps that I outlined above. So the CR “theory” of social structure, is precisely what you think. Social structure is composed of individuals, organized by a set of relations that form a coherent (configured) whole. This whole (social structure) is now a real entity endowed with its own causal powers, which now (may) exert “downward causation” on the individual’s the constitute it. These causal powers are not reducible to those of the individuals that constitute it. This how CR cashes in what John Levi Martin has referred to as the “substantive hunch” that animates all sociological research. “The social” emerges from the powers and activities of individuals but it never ultimately resolves itself into an aggregation of those powers and activities. Note that CR is opposed to any form of ontological reduction whether it is “downwards” or “upwards.” Thus attempts to reduce social structure to the mental or interactional level are “downward conflationist” and attempts to reduce individuals to social structure (or language or what have you), are “upward conflationist.” Thus, the “first” Archer trilogy can be read in this way. First, on the non-reducibility (and ontological independence between) social structure in relation to the individual or individual activity, then “culture” in relation to the individual or individual interaction, and later (in reverse) personal agency in relation to either social structure or culture.

Essentially, the stratified ontology postulate must be respected. Any attempt to simplify the ontological picture is rejected as so much covert (or overt) reductionism or “conflation.” Note that “conflation” is not technically a formal error of reasoning (as is begging the question) but simply an attempt by a theorist to simplify the ontological picture by abandoning the ontological democracy or ontological emergence postulates. A lot of the times CR theorists (like Archer) reject conflation as if it was such an error in reasoning, when in fact it is a substantive argument that cannot be dismissed in such an easy way. Note that this is weird because both the ontological democracy and the ontological emergence argument are themselves non-demonstrable but substantively important propositions in CR. Thus, most CR attempts to dismiss either reductionist or simplifying ontologies themselves do commit such a formal error of reasoning, namely, begging the question in favor of ontological emergence and ontological democracy.

Another way to make a CR argument is to start with a predetermined high level entity of choice. This kind of CR argument is more “defensive” than constructive. Here the analyst picks an entity the real status of which has (for some reason) become controversial, either because some theorists purport to show that it does not “really” exist (meaning that it is just a shorthand way to talk about some aggregate of actually existing lower level entities), or is not required to generate scientific accounts of some slice of the world (ontological simplification or reduction a la caloric or phlogiston). Here CR arguments essentially use the ontological democracy postulate to simply say that the preferred whole has ontological independence from either the lower constituents or higher level entities to which others seek to reduce the focal entity. Moreover, the CR theorist may argue that this ontological independence is demonstrated by the fact that this entity has (actualized and/or empirically observable) causal powers, once again above and beyond those provided by the lower level (or higher level ) entities or processes usually trotted out to “reduce it away.” This applies in particular to the “humanist” strand of CR that attempts to defend specific causal powers that are seen as inherent properties of persons (e.g. reflexivity in Archer’s case) or even the very notion of person (in Chris Smith’s What is a Person?) as an emergent whole endowed with specific causal powers, properties and propensities.

To recap, CR is a complex object composed of many parts. But not all parts are of the same nature. I have distinguished between roughly three parts, organized according to the generality of the claim and the specificity of the substantive points made. In this respect, I would distinguish between:

1) The parts that CR shares with all “vanilla” realisms. This includes the postulate of ontological realism (mind-independence of the existence of reality), the transitive/intransitive distinction, the EAR distinction, and so on. In itself, none of these theses make CR particularly distinctive, unique or useful. If you disagree with CR at this level, based on irrealist premises, congratulations. You are insane.

2) The Aristotelian ontology.- This specifies the kind of realism that CR proposes. Here things get more interesting, because there is actual philosophical debate about this (nobody seriously defends irrealist positions in Philosophy any more and most sociologists just like to pretend to be irrealists to show off at parties). Here CR could play a role in philosophical debates insofar as a neo-Aristotelian approach to realism and explanation is a coherent position in Philosophy of Science (although it is not without its challengers). Here belongs (among other things) the specific CR conceptualizations of objects and entities, the causal (dispositional) powers ontology (when hooked to the EAR distinction) and the specific “Theory of Science” and the “Theory of Explanation” that follows from these (essentially endorsing mechanismic and systems explanation over reductive, covering law stories). This is what I believe is the best ontological move and CR should be commended in this respect.

3) The stratified ontology.- This comes from yoking (1) and (2) to the ontological emergence and ontological democracy postulate. This is where you can find a lot of “controversial” (where by controversial I mean worth arguing about, worth specifying, worth clarifying, and in some cases worth rejecting) arguments in CR. These are of three types: ontological emergence arguments, augment the standard common-sense ontology of material entities to argue for the existence of higher level non-material entities; thus “social structures” are as real as the couch that you are lying on; the danger here is a world that comes to populated with a host of emergent “entities” with no principled way of deciding which ones are in fact real (beyond the theorist’s taste). This is the problem of ontological inflation, (2) “Downward causation” arguments add this postulate to suggest that the emergent (non-material or material) entities not only “exist” in a passive sense, but actually exert causal effect on lower level components or other higher-level entities, (3) “ontological independence” arguments attempt to show that a particular sort of entity that is usually done violence to in standard (reductionist) accounts has a level of ontological integrity that cannot be impugned and has a set of causal powers that cannot be dismissed. In humanist and personalist accounts, this entity is “the person” along with a host of powers and capacities that are usually blunted in “social-scientific” accounts (e.g. persons as centers of moral purpose) and the enemies are the positions that attempt to explain away these powers or capacities or that attempt to show that the don’t matter as much as other entities (e.g. “social structure”).

4) Continuing extensions of the stratified ontology argument.- This is the part of CR that has drawn (an unfair) amount of attention, because it extends the same set of arguments to defend both the reality but also the causal powers of a set of entities that (a) a lot of people are diffident about according the same level of reality to as the standard material entities, and (b) things that most people would have difficulty even calling entities. These may be “norms,” “the mental,” “the cultural,” “the discursive,” and “levels of reality” above and beyond the plain old material/empirical world that we all know and love (e.g. super-empirical domains of reality). You can see how CR can get controversial here.

5) Additional stuff.- A lot of other CR arguments do not directly follow from any of these, but are added as supplementary premises to round out CR as a holistic perspective. For instance, the rejection of the fact-value distinction in science is not really a logical derivation from the theory of science or the neo-Aristotelian ontology, and neither is the “judgmental rationality” postulate (that science progresses, gradually gets at the truth, etc.). I mean all realisms presuppose that we get better at science, but this is not really a logical derivation from realist premises (as argued by Arthur Fine). The fact/value thing is in the same boat, because it requires a detour through a lot of controversial group (3) and group (4) territory to be made to stick. For instance, given that persons are emergent entities, endowed with non-arbitrary properties and powers, then the “relativist” arguments that any social arrangement is as good as any other for the flourishing of personhood is clearly not valid. This means that social scientists have to take a strong stance on the value question (hence sociological inquiry cannot be value neutral). Because a mixture of Aristotelian ontology and ontological emergentism applied to human nature is incompatible with moral (and social-institutional) relativism, the the fact value distinction in social science is untenable. However, note that to get there a lot of other premises, sub-premises, and substantive arguments for the reality of persons as emergent, neo-Aristotelian entities have to be accepted as valid. In this sense the fact/value thing is only a derivation from certain extensions of CR into controversial territory. As already intimated, What is a Person? is a (well-argued!) piece of controversial CR precisely in this sense.

Note that this clarifies the “giant package” versus “minimalist” CR debate. Let’s go back to the cable analogy. So you are considering signing up for CR? Here’s the deal: The “basic” CR package would (in my view) be any acceptance of (1) and (2) (with some but not all elements of (3)). In this sense, I am a Critical Realist (and so should you). The “standard” CR package includes in addition to (1), (2) and all of (3), some elements of (4). Here we enter controversial territory, because a lot of CR arguments for the “reality” of this or that are not as tight or well-argued as their proponents suppose. In their worst forms, they resolve themselves into picking your favorite thing (e.g. self-reflexivity), and then calling it “real” and “causally powerful” because “emergent.” It is no surprise that Archer’s weakest work is of this (most recent) ilk. Here the obsession with ontological democracy prevents any consideration of ontological simplification or actual ontological stratification (meaning getting clear on which causal powers matter most rather than assigning each one their preferred, isolated level). Finally, the “turbo” package requires that you sign up for (1) through (5), this of course is undeniably controversial, because here CR goes from being a philosophy of scientific practice to being a philosophy of life, the universe and everything. Sometimes CR people seem to act surprised that people may be reluctant to adopt a philosophy of life, but I believe that this has to do with their penchant to suppose that once you accept the basic, then the chain or reasoning that will lead you to the standard and the turbo follows inexorably and unproblematically.

This is absolutely not the case, and this where CR folk would benefit most from talking to people who are not fully committed to the turbo, but who (like other sane people) are already 80% into the basic (and maybe even the standard). My sense is that we should certainly be arguing about the right things, and in my view the right things are at the central node (3), because this is the where the key set of argumentative devices that allows CR people to derive substantively meaningful (“controversial”) conclusions (both at that level—arguments for the reality of “social structure”—and about type (4) and (5) matters), and where most attempts to provide a workable ontology for the social sciences are either going to be cashed in, or be rejected as aesthetically pleasing formulations of dubious practical utility.

Three thousand more words on critical realism

The continuing brouhaha over Fabio’s (fallaciously premised) post*, and Kieran’s clarification and response has actually been much more informative than I thought it would be. While I agree that this forum is not the most adequate to seriously explore intellectual issues, it does have a (latent?) function that I consider equally as valuable in all intellectual endeavors, which is the creation of a modicum of common knowledge about certain stances, premises and even valuational judgments. CR is a great intellectual object in the contemporary intellectual marketplace precisely because of the fact that it seems to demand an intellectual response (whether by critics or proponents) thus forcing people (who otherwise wouldn’t) to take a stance. The response may range from (seemingly facile) dismissal (maybe involving dairy products), to curiosity (what the heck is it?), to considered criticism, to ho hum neutralism, to critical acceptance, or to (sock-puppet aided) uncritical acceptance. But the point is that it is actually fun to see people align themselves vis a vis CR because it provides an opportunity for those people to actually lay their cards on the table in way that seldom happens in their more considered academic work.

My own stance vis a vis CR is mostly positive. When reading CR or CR-inflected work, I seldom find myself vehemently disagreeing or shaking my head vigorously (this in itself I find a bit suspicious, but more on that below). I find most of the epistemological, and meta-methodological recommendations of people who have been influenced by CR (like my colleague Chris Smith, Phil Gorski, or George Steinmetz, or Margaret Archer) fruitful and useful, and in some sense believe that some of the most important of these are already part of sociological best practice. I think some of the work on “social structure” that has been written by CR-oriented folk (Doug Porpora and Margaret Archer early on and more recently Dave Elder-Vass) important reading, especially if you want to think straight about that hornet’s nest of issues. So I don’t think that CR is “lame.” Although like any multi-author, somewhat loose cluster of writings, I have indeed come across some work that claims to be CR which is indeed lame. But that would apply to anything (there are examples of lame pragmatism, lame field theory, lame network analysis, lame symbolic interactionism, etc. without making any of these lines of thought “lame” in their entirety).

That said, I agree with the basic descriptive premises of Kieran’s post. So this post is structured as a way to try to unhook the fruitful observations that Kieran made from the vociferous name-calling and defensive over-reactions to which these sort of things can lead. So think of this as my own reflections of what this implies for CR’s attempt to provide a unifying philosophical picture for sociology.

three sociologies of knowledge