Archive for the ‘current events’ Category

hidden externalities: when failed states prioritize business over education

Much has been discussed in the media about the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic; for example, to compensate for the absence of coordinated support, working mothers are carrying more caregiving responsibilities. However, the full range of externalities resulting from governmental and organizational decisions (or in the case of some governments, “non”-decisions which are decisions in practice) often are less visible during the pandemic. Some of these externalities – impacts on health and well-being, careers and earnings, educational attainment, etc. – won’t be apparent until much later. The most disadvantaged populations will likely bear the brunt of these; organizations charged with addressing equity issues, such as schools and universities, will grapple over how to respond to these in the years ahead.

In this blog post, I’ll discuss one under-discussed implication of what’s happening in NYC as an example, and how other organizations have had to adjust as a result. Mayor DeBlasio has discussed how NYC public schools will close if NYC’s positivity rate averages 3% over 7 days. At the same time, indoor dining, bars, and gyms have remained open, albeit in reduced capacity. People, especially parents and experts, including medical professionals, are questioning this prioritization of business establishments over schools across the US.

Since the start of the 2020 school year, NYC public schools has offered limited in-person instruction. A few informal conversations I’ve had with parents at NYC public schools revealed that they found the blended option an unviable one. Due to capacity and staffing issues, a public school’s blended learning schedules could vary over the weeks. For example, with a 1:2:2 schedule, a student has 1 day of in person school the first week, followed by 2 days in person the following week, then another 2 days in person the third week. Moreover, which days a student can attend in-person school may not be the same across the weeks. This might partially explain why only a quarter of families have elected these. Overall, both “options” of blended learning and online learning assume that families have flexibility and/or financial resources to pay for help.

What’s the cost of such arrangements? People have already acknowledged that parents, and in particular, mothers, bear the brunt of managing at-home schooling while working from home. But there is another hidden externality that several of my CUNY freshmen students who live with their families have shared with me. While their parents work to pay rent and other expenses, some undergraduates must support their younger siblings’ online learning. Other students are caregiving for relatives, such as a disabled parent, sometimes while recovering from illnesses themselves. Undergraduates must coordinate other household responsibilities in between managing their own online college classes and additional paid work. Without a physical university campus that they can go to for in-person classes (excluding labs and studio classes that are socially distanced) or as study spaces, students don’t have physical buffers that can insulate them against these unanticipated responsibilities and allow them to focus on their learning, interests, and connections.

Drawing on the financial resources available to them and shaping plans around “stabilizing gambits,” several elite universities and small liberal arts colleges have sustained quality education for their students with their in-person classes, frequent testing, and sharing of information among dorm-dwellers. But in the absence of any effective, coordinated federal response to the pandemic in the US, what can public university instructors do to ensure that their undergraduate students have a shot at quality learning experiences? So far, I’ve assigned newly published texts that guide readers through how to more critically analyze systems. I’ve turned to having students documenting their experiences, in the hopes of applying what they have learned to re-design systems that work for more diverse populations. I’ve tried to use synchronous classes as community-building sessions, coupled with feedback opportunities on how to channel our courses to meet their needs and interests. I’ve devoted parts of class sessions to explaining how to navigate the university, including how to select majors and classes and connect with instructors. I’ve connected research skills to interpreting the firehose of statistics and studies about pandemic, to help people ascertain risks so that they can make more informed decisions that protect themselves and their communities and educate others. I’ve attempted to shift expectations for what learning can look like in the absence of face-to-face contact. Since many of the relational dimensions that we took for granted in conventional face-to-face classes are now missing (i.e., visual cues, physical co-presence), I’ve encouraged people to be mutually supportive in other ways, like using the chat / comments function. In between grading and class prep, I’ve written letters of recommendation, usually on very short notice, so that CUNY students can tap needed emergency scholarships or pursue tenure-track jobs. In the meantime, our CUNY programs have tried to enhance outreach as households experience illness and job loss, with emergency funds and campus food pantries mapping where students reside and sending mobile vans to deliver groceries, in an effort to mitigate food insecurity.

Like other scholars, I’ve also revealed, in the virtual classroom, meetings, and conferences, how the gulf between work/family policies is an everyday, shared reality – something that should be acknowledged, rather than hidden away for performative reasons. Eagle-eyed viewers are likely to periodically spot my child sitting by my side in a zoom meeting, assisting me by taking class attendance, or even typing on documents in the background. My capacities to support undergraduate and graduate learning, as well as contribute to the academic commons by reviewing manuscripts and co-organizing academic conferences, have depended on my daughter attending her school in-person. Faculty and staff at her school have implemented herculean practices to make face-to-face learning happen, and families have followed agreements about reducing risks outside of school to maintain in-person learning. That said, given current policy decisions, it’s just a matter of time when I will join other working parents and my CUNY undergraduates making a daily, hour-by-hour complex calculus of what can be done when all-age learners are at home.

All of these adjustments and experimental practices are just baby steps circumnavigating collective issues. These liminal times can offer opportunities to rethink how we enact our supposed values in systems and institutions. For instance, do we allow certain organizations and unresponsive elected leaders to continue to transfer externalities to those who are least prepared to bear them? Do we charge individual organizations and dedicated members, with their disparate access to resources, to struggle with how to serve their populations’ needs? Or, do we more closely examine how can we redesign systems to recognize and support more persons?

extended q & a with daniel beunza about taking the floor: models, morals, and management in a wall st. trading room

Following 9/11, Wall St. firms struggled to re-establish routines in temporary offices. Many financial firms subsequently made contingency plans by building or renting disaster recovery sites. As we see now, these contingency plans relied upon certain assumptions that did not anticipate current pandemic conditions:

The coronavirus outbreak threw a wrench into the continuity planning that many Wall Street companies had put in place since at least the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks. Those plans were largely built around the idea that if trading at a bank headquarters was knocked off-line, groups of traders would decamp to satellite trading floors outside the radius of whatever disaster had befallen New York. But those plans quickly became unworkable, given the dangers of infections from coronavirus for virtually all office work that puts people close to one another.

“This is really not the disaster that they had planned for,” said Daniel Beunza, a business professor at the City University of London, who has studied and recently written a book on bank trading floor culture.

Just in time for us to understand the importance of face-to-face proximity in the workplace, Beunza has a new book Taking the Floor: Models, Morals, and Management in a Wall Street Trading Room (2019, Princeton University Press) based on years of ethnographic observation. Beunza kindly agreed to an extended Q&A about his research.

Q: “Chapter 1 of your book describes how you were able to gain access to an organization, after two failed attempts. Quinn, a classmate, offers to introduce you to a former co-worker of his from finance: Bob, now the head of a derivatives trading floor at International Securities. You meet with Bob and observe activities, where you realize that the trading floor no longer looks or sounds like prior literature’s depictions. After this first meeting, you send over “sanitized” field notes about your first visit (p. 32), and you meet again with Bob, who has even read and reflected on these field notes. This second meeting to go over your initial impressions starts a longer relationship between yourself and this unit of International Securities [a pseudonym]. You have your own desk on the floor, where you can write down notes.

In subsequent years, after the bulk of your field research ends, you invite Bob to come as a guest speaker in your Columbia Business School classes. Your book recounts how bringing in Bob not only offers the MBA finance students perspective on their desired field of employment, but might also smooth over student-professor relations, especially since teaching evaluations matter. Afterwards, Bob comments on the students’ late arrivals to class and how he handled the equivalent in his workplace, helping you to understand divergences in your respective approaches to relationships and organizations.

In chapter 8, your book describes your interview with Peter, an executive who had worked with Bob at International Securities. Peter describes how most Wall Streeters might react to researchers’ requests for access:

“Bob is a curious dude. He reads a lot. He befriended you because he was curious. Most guys on Wall Street would say, ‘Oh, another academic from Columbia? Thank you very much. Goodbye. I don’t have time for you. You’re going to teach me a new algorithm? You’re going to teach me something big? Okay. Come in and sit down. And I’ll pay you, by the way.’ But a sociologist? ‘Wrong person on my trading floor. A desk? No. You’re crazy. Go away.’ So Bob has those qualities, and many of the people you see here have those qualities” (p. 168).

Peter’s comment, along with your observations, also offers a colleague’s assessment of Bob’s management style. Rather than relying on money as an incentive or fear as a motivation, Bob hires people ‘who were a little different,’ and he cultivates relationships by spending time with employees during work hours in supportive and subtle ways, according to Peter. (Elsewhere, your book notes that this does not extend to colleagues having drinks outside of work – a way that other organizations can cultivate informal relations.)

Your book argues that such practices, when coupled with clearly communicated values delineating permissible and impermissible actions, constitute “proximate control.” Such efforts can check potential “model-based moral disengagement” where parties focus on spot transactions over longer-term relationships; this focus can damage banks’ viability and legitimacy. In other words, your book posits that face-to-face contact can channel decisions and actions, potentially reigning in the damaging unknown unknowns that could be unleashed by complex financial models.

First, the content question:

These analyses remind me of older discussions about managerial techniques (notably, Chester Barnard, who built upon Mary Parker Follet’s ideas) and mantras (Henri Fayol’s span of control), as well as more recent ones about corporate culture. Indeed, your book acknowledges that Bob’s “small village” approach may seem “retro” (p. 170).

That said, your book underscores how people and organizations still benefit from face-to-face connection and interdependency. Some workplaces increasingly de-emphasize these aspects, as work has become virtually mediated, distributed, asynchronous, etc. Why and how does it matter so much more now? How are these findings applicable beyond the financial sector?”

Beunza: “Face-to-face connections are crucial, but I should add that the perspective coming out of the book is not a luddite rejection of technology. The book makes a sharp distinction between valuation and control. The use of models to value securities is in many ways a more advanced and more legitimate way of pursing advantage on Wall Street than alternatives such as privileged information.

However, the use of models for the purpose of control raises very serious concerns about justice in the organization. Employees are quickly offended with a model built into a control tool penalizes them for something they did correctly, or allows for gaming the system. If perceptions of injustice become recurring, there is a danger that employees will morally disengage at work, that is, no longer feel bad when they breach their own moral principles. At that point, employees lose their own internal moral constraints, and become free to pursue their interests, unconstrained. That is a very dangerous situation.

I would argue this is applicable to all attempts at mechanistically controlling employees, including other industries such as the Tech sector, and not-for-profit sectors such as academia. Some of the warmest receptions of my book I have seen are by academics in the UK, who confront a mechanistic Research Assessment Exercise that quantifies the value of their research output.”

Q: “Second, the reflexivity question:

Did you anticipate how Bob’s visit to your Columbia Business School classroom might provide additional insight into your own “management” [facilitation?] style and your research regarding financial models and organizations? How have research and teaching offered synergistic boosts to respective responsibilities? How do such cross-over experiences – discussing issues that arise in researcher’s organizations, which probably constitute “extreme” cases in some dimensions – help with developing organizational theory?”

Beunza: “Back in 2007, I had a diffuse sense that I would learn something of significance when inviting Bob to my classroom, but was not sure what. Before I saw him, I suspected that my original view of him as a non-hierarchical, flat-organization type of manager might not quite be entirely accurate, as a former colleague of him said he was a “control freak.” But I had no way of articulating my doubts, or take them forward. His visit proved essential in that regard. As soon as he showed up and established authority with my unruly students, I understood there was something I had missed in my three years of fieldwork. And so I set out to ask him about it.

More generally, my teaching was instrumental in understanding my research. MBA students at Columbia Business School did not take my authority for granted. I had to earn it by probing, questioning, and genuinely illuminating them. So, I develop a gut feeling for what authority is and feels like. This helped me understand that asking middle managers to abdicate their decisions in a model (which is what the introduction of quantitative risk management entailed in the late 90s) is a fundamental challenge to the organization.”

Q: “This, a methods question:

Peter’s comment underscores what Michel Anteby (2016) depicts as “field embrace” – how an organization welcomes a researcher – as opposed to denying or limiting access. Anteby notes how organizations react to researchers’ requests to access is a form of data. How did Bob’s welcoming you and continued conversations over the years shed additional insight into your phenomena?”

Beunza: “Anteby is right that the bank’s form of embrace is data. Indeed, I could not quite understand why International Securities embraced my presence in the early 2000s until 2015, when Bob laid out for me the grand tour of his life and career, and allowed me to understand just how much of an experiment the trading floor I had observed was. Bob truly needed someone to witness what he had done, react back to it, accept or challenge the new organization design. And this was the most fundamental observation of the research process – the one that motivates the book. My entire book is an answer to one question, “how did Bob’s experiment perform?” that I could only pose once I understood why he had embraced my presence.”

————– Read more after the jump ———— Read the rest of this entry »

interstitial bureaucracy: high performing governmental agencies operating in ineffective governments

Back in February (which now seems like an eternity from a fast-disappearing alternate reality), sociologist and organizational researcher Erin Metz McDonnell virtually visited my graduate Organizations, Markets, and the State course to talk about her research on high performing governmental agencies in Ghana. McDonnell initiated an electrifying and dynamic discussion about the applicability of her research findings. She also shared her experience with the opaque process of how researchers form projects that contribute to public knowledge.

Many of her observations about organizing practices are particularly timely now that the US and other nation-states face extreme challenges that demand more proactive, rather than retroactive, preparations for pandemic conditions.

Here’s a digest of what we learned:

- Why Ghana? Prior to graduate school, McDonnell went to Ghana on a Fulbright award. These experiences helped her question conventional organizational orthodoxy, including generalized statements about “states do this” built on research conducted in North America. Using such observed disjunctures between the organizational canon and her lived experience, McDonnell refined research questions. When she returned to Ghana, she identified high performing governmental units and undertook interviews.

- Why did McDonnell include other cases, including 19th century US, early 21st century China, mid-20th century Kenya, and early 21st century Nigeria? McDonnell discussed the importance of using research in other countries and time periods to further flesh out dimensions of interstitial bureaucracy.

- How did McDonnell coin the term interstitial bureaucracy? Reviewers didn’t like McDonnell’s originally proposed term to describe the habits and practices of effective bureaucrats. “Subcultural bureaucracy” was perceived as too swinging 1960s, according to reviewers.

- What can Ghana reveal about N. American’s abhorrence of organizational slack? McDonnell explained that high performing bureaucracies in Ghana reveal the importance of slack, which has been characterized as wasteful in N. American’s “lean” organizations. Cross training and “redundancies” help organizations to continue functioning when workers are sick or have difficulties with getting to work.

- Isn’t staff turn-over, where people leave after a few years for better paying jobs in the private sector or elsewhere, a problem? Interestingly, McDonnell considered staff turn-over a small cost to pay – she opined that securing qualified, diligent workers, even for a few years, is better than none. (Grad students added that some career bureaucrats become less effective over time)

- What can governmental agencies do to protect against having to hire (ineffective) political appointees? McDonnell explained how specifying relevant credentials in field (i.e., a degree in chemistry) can ensure the likelihood of hiring qualified persons to staff agencies.

For more, please check out McDonnell’s new book Patchwork Leviathan: Pockets of Bureaucratic Effectiveness in Developing States from Princeton University Press. Also, congrats to McDonnell on her NSF Career award!

book spotlight: beyond technonationalism by kathryn ibata-arens

At SASE 2019 in the New School, NYC, I served as a critic on an author-meets-critic session for Vincent de Paul Professor of Political Science Kathryn Ibata-Arens‘s latest book, Beyond Technonationalism: Biomedical Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Asia.

Here, I’ll share my critic’s comments in the hopes that you will consider reading or assigning this book and perhaps bringing the author, an organizations researcher and Asia studies specialist at DePaul, in for an invigorating talk!

“Ibata-Arens’s book demonstrates impressive mastery in its coverage of how 4 countries address a pressing policy question that concerns all nation-states, especially those with shifting markets and labor pools. With its 4 cases (Japan, China, India, and Singapore), Beyond Technonationalism: Biomedical Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Asia covers impressive scope in explicating the organizational dimensions and national governmental policies that promote – or inhibit – innovations and entrepreneurship in markets.

The book deftly compares cases with rich contextual details about nation-states’ polices and examples of ventures that have thrived under these policies. Throughout, the book offers cautionary stories details how innovation policies may be undercut by concurrent forces. Corruption, in particular, can suppress innovation. Espionage also makes an appearance, with China copying’s Japan’s JR rail-line specs, but according to an anonymous Japanese official source, is considered in ill taste to openly mention in polite company. Openness to immigration and migration policies also impact national capacity to build tacit knowledge needed for entrepreneurial ventures. Finally, as many of us in the academy are intimately familiar, demonstrating bureaucratic accountability can consume time and resources otherwise spent on productive research activities.

As always, with projects of this breadth, choices must made in what to amplify and highlight in the analysis. Perhaps because I am a sociologist, what could be developed more – perhaps for another related project – are highlighting the consequences of what happens when nation-states and organizations permit or feed relational inequality mechanisms at the interpersonal, intra-organizational, interorganizational, and transnational levels. When we allow companies and other organizations to, for example, amplify gender inequalities through practices that favor advantaged groups over other groups, what’s diminished, even for the advantaged groups?

Such points appear throughout the book, as sort of bon mots of surprise, described inequality most explicitly with India’s efforts to rectify its stratifying caste system with quotas and Singapore’s efforts to promote meritocracy based on talent. The book also alludes to inequality more subtly with references to Japan’s insularity, particularly regarding immigration and migration. To a less obvious degree, inequality mechanisms are apparent in China’s reliance upon guanxi networks, which favors those who are well-connected. Here, we can see the impact of not channeling talent, whether talent is lost to outright exploitation of labor or social closure efforts that advantage some at the expense of others.

But ultimately individuals, organizations, and nations may not particularly care about how they waste individual and collective human potential. At best, they may signal muted attention to these issues via symbolic statements; at worst, in the pursuit of multiple, competing interests such as consolidating power and resources for a few, they may enshrine and even celebrate practices that deny basic dignities to whole swathes of our communities.

Another area that warrants more highlighting are various nations’ interdependence, transnationally, with various organizations. These include higher education organizations in the US and Europe that train students and encourage research/entrepreneurial start-ups/partnerships. Also, nations are also dependent upon receiving countries’ policies on immigration. This is especially apparent now with the election of publicly elected officials who promote divisions based on national origin and other categorical distinctions, dampening the types and numbers of migrants who can train in the US and elsewhere.

Finally, I wonder what else could be discerned by looking into the state, at a more granular level, as a field of departments and policies that are mostly decoupled and at odds. Particularly in China, we can see regional vs. centralized government struggles.”

During the author-meets-critics session, Ibata-Arens described how nation-states are increasingly concerned about the implications of elected officials upon immigration policy and by extension, transnational relationships necessary to innovation that could be severed if immigration policies become more restrictive.

Several other experts have weighed in on the book’s merits:

“Kathryn Ibata-Arens, who has excelled in her work on the development of technology in Japan, has here extended her research to consider the development of techno-nationalism in other Asian countries as well: China, Singapore, Japan, and India. She finds that these countries now pursue techno-nationalism by linking up with international developments to keep up with the latest technology in the United States and elsewhere. The book is a creative and original analysis of the changing nature of techno-nationalism.”—Ezra F. Vogel, Harvard University

“Ibata-Arens examines how tacit knowledge enables technology development and how business, academic, and kinship networks foster knowledge creation and transfer. The empirically rich cases treat “networked technonationalist” biotech strategies with Japanese, Chinese, Indian, and Singaporean characteristics. Essential reading for industry analysts of global bio-pharma and political economists seeking an alternative to tropes of economic liberalism and statist mercantilism.”—Kenneth A. Oye, Professor of Political Science and Data, Systems, and Society, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

“In Beyond Technonationalism, Ibata-Arens encourages us to look beyond the Asian developmental state model, noting how the model is increasingly unsuited for first-order innovation in the biomedical sector. She situates state policies and strategies in the technonationalist framework and argues that while all economies are technonationalist to some degree, in China, India, Singapore and Japan, the processes by which the innovation-driven state has emerged differ in important ways. Beyond Technonationalism is comparative analysis at its best. That it examines some of the world’s most important economies makes it a timely and important read.”—Joseph Wong, Ralph and Roz Halbert Professor of Innovation Munk School of Global Affairs, University of Toronto

“Kathryn Ibata-Arens masterfully weaves a comparative story of how ambitious states in Asia are promoting their bio-tech industry by cleverly linking domestic efforts with global forces. Empirically rich and analytically insightful, she reveals by creatively eschewing liberalism and selectively using nationalism, states are both promoting entrepreneurship and innovation in their bio-medical industry and meeting social, health, and economic challenges as well.”—Anthony P. D’Costa, Eminent Scholar in Global Studies and Professor of Economics, University of Alabama, Huntsville

facebook’s data scandal won’t make much of a difference: a comment on interpersonal vs. structural privacy

Right now, Facebook is under tremendous criticism because the firm inappropriately allowed a third party to use their data. There is much consternation and even Facebook’s stock price has taken a hit. But from my view, I don’t think much will change. Why? People are very comfortable with a lack of “structural privacy.” In contrast, they deeply resent the violation of “interpersonal privacy.”

These discussions assume that there is a single thing called “privacy” and that people will get upset when they don’t have privacy. This assumption comes from the nature of human interaction pre-industrial revolution. Before the rise of modern information systems, whether they be Census documents or Facebook meta-data, privacy meant that people in your immediate environment did not have access to all the information about you. This even applied to families. Many of us, for example, have diaries that we don’t want other family members to read.

Why do we value “interpersonal” privacy? There are many reasons. We may not want our immediately relations to know that we are critical of what they do. Maybe we don’t want our neighbors to know that we like strange food. Or maybe we don’t want our employer to know that we don’t like them so much. What these reasons and others share in common is that the possession of knowledge prevents inter-personal conflict. Without privacy, we wouldn’t be free to form opinions and we would likely be in constant conflict with each other.

The Cambridge Analytica scandal and the Snowden revelations are about a different flavor of privacy – one that I call “structural privacy.” In the modern age, all kinds of institutions collect data on us. It could be the phone company, or the Internal Revenue Service, or Facebook. However, the data is often summarized so that it doesn’t involve a single person. When people access it, they rarely have any personal relationship to the people in the data base. Thus, people don’t usually experience interpersonal conflict when they loose “structural privacy,” the privacy that is maintained when information is collected by institutions for collective purposes. The IRS agent who peeks at your return or the Facebook employee who looks at your friendship list almost never know you and they don’t care.

This suggests that Facebook will probably be fine in the long term. People, in general, seem to be ok with the fact that firms and states routinely violate their structural privacy. The Snowden revelations barely elicited any push back from the public and almost no change in public policy. Here, I think the same process will play out. As long as Facebook can maintain privacy at the interpersonal level, they can carry on as usual.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

the iraq war, a forever war

On September 10, 2001, I never imagined that the US would be involved in an endless war in Iraq, a conflict that still takes thousands of lives each year. Even after the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington, I did not imagine that the US would be involved in Iraq fifteen years later, sending money and advisers in a nearly endless stream.

What horrifies me is the human cost. When I was doing the research for Party in the Street, I met people who had lived in Iraq or served in Iraq. Meeting and talking to them showed me the immediate cost of the war. Families lost. Lives shattered. Faces disfigured. Children who committed suicide.

What now? The Iraq War is a “Keynesian war,” to used a phrase coined by sociologist Sidney Tarrow. Modern wars are often fought with borrowed money and volunteer armies. They are kept out of the public view. They are pursued in ways that prevent scrutiny and public input. That means that the war in Iraq, and Afghanistan, can continue in one way or another for quite a while.

I am not a pessimist. But I am a realist, this will continue for a while before it gets better. My hope is that Iraq follows the path of the Philippines after it was occupied by the US in the early 20th century. They had a long insurrection but then a period of modernization and integration into the global economy. Sadly, we’ve already had the violence, and it’s time to move on.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

defending free speech the right way: three cheers for gabriel rossman

Recently, a UCLA conservative student group invited Milo Yiannopolous to speak at the campus. Then, UCLA sociologist (and former orgtheory guest) Gabriel Rossman wrote an open letter to the Bruin Republicans urging them to rescind the invitation, which they did. Excerpts from the letter, as published in The Weekly Standard:

The most important reason not to host such a talk is that it is evil on the merits. Your conscience should tell you that you never want anything to do with someone whose entire career is not reasoned argument, but shock jock performance art. In the 1980s conservatives made fun of “artists” who defecated on stage for the purpose of upsetting conservatives. Now apparently, conservatives are willing to embrace a man who says despicable things for the purpose of “triggering snowflakes.” The change in performance art from the fecal era to the present is yet another sign that no matter how low civilization goes, there is still room for further decline.

I want to be clear that my point here is not that some people will be offended, but that the speaker is purely malicious.

I could not agree more. Gabriel makes it clear that he is defending their right to have a speaker, but that it is unwise and unethical to invite this particular speaker. On Twitter, Gabriel also makes it clear that there was a lot of internal pressure to cancel this talk, and that the open letter was a secondary part of the story.

I want to add a few words about the defense of free speech, drawn from Gabriel’s letter. First, Gabriel avoids a common mistake – no where does he oppose the talk because he thinks that having the talk will somehow legitimize racism or undermine UCLA. Universities are hardy creatures and hosting a shock jock conservative will not have any appreciable effect on racism in the larger society.

Second, he focuses on wisdom – is this really the right thing to do? Does inviting Yiannopolous really promote truth seeking? This is the difference between hosting a “conservative performance art” event and a conservative intellectual with genuinely held beliefs that need to be debated. I think this is the difference between inviting Charles Murray – who provides evidence and is willing to debate – and Yiannopolous. One has controversial views, the other is a controversy machine. There is a huge difference.

Finally, this approach provides a broader defense of free speech and debate for all people. On a basic level, students and faculty have been given the privilege to invite who ever they want to campus. And that means some nasty people will be invited from time to time and we should support that right.

On a deeper level, we need a higher standard to decide which speech should be actively supported. If someone provides data and can treat others civilly in debate, we should be very tolerant. If someone shows a basic mastery of argument and analysis of evidence, they deserve a hearing. Conversely, if a faculty member is a scholar in good standing, we should be forgiving if they mis-speak in public.

We need to appreciate that the core of the university is not free speech. Rather, free speech is a starting point. What real scholars do is select which speech merits a spotlight and an analysis and that’s a crucial activity.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

three cheers for california!

Marijuana is now legal in the state of California and a few other states. I applaud this move. I am glad that the arrests and criminalization are coming to an end. The ingestion of narcotics should be treated the way we treat alcohol. It should be legal and you should only be prosecuted if your behavior endangers others. And if you harm yourself, go see the doctor. You shouldn’t go to prison. Let’s hope this is part of a bigger trend.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

why contemporary architecture sucks and why economic sociology is the future we’ve been waiting for

Biranna Rennix and Nathan Robinson have a long, but well-written essay called “Why You Hate Contemporary Architecture, and If You Don’t Why You Should”. The hook: name one example of a building built in the last 70 years that stands up to anything built before the War? You, like me, probably have a hard time thinking of an answer.

The explanation they offer is that this isn’t just a question of taste. It is that computers have allowed architects to do things now that weren’t possible before the war. So we don’t design buildings anymore, we engineer them. And the engineering possibilities far outstrip normal human capability. Combine that with capitalism’s emphasis on efficiency and what you get is buildings that are both ugly and inhuman.

As I started reading it, I was thinking to myself “it is so nice to read something long and thoughtful that has nothing to do with Donald Trump.” But of course, it’s not that simple. Eventually, I found myself substituting the phrase “public policy” for “architecture.” And in doing so, I found myself coming to an explanation for the “populist moment” we are living through: Just as post-war architecture became more and more focused on efficiency and technical superiority at the expense of feelings and human needs, public policy in the post-War period has become more distant, abstract and technical.

I sympathize with the reaction of elite architecture professors who resist the idea that the solution to the problem of contemporary architecture is to retreat into “nostalgic” buildings. Similarly, I resist the idea that the response to the critique of contemporary public policy is to go back to a nostalgic pastiche of an vaguely defined golden era.

But here’s the thing: even if I don’t agree with the treatment for the illness I can’t ignore the underlying diagnosis. Massive policy projects—whether the European Union or reforming the American health care system—are Le Corbusian in their ambition and intelligence as well as their capacity for mass alienation. And that policy alienation has produced a real and consequential backlash that we should not ignore (despite our moment of joy over the results in Alabama–go ‘Bama!).

The upshot of the architecture article is a call to reintroduce fallibility and limited human capacity into processes by which buildings get built. Venice and Bruges resulted from the work of builders who contributed in ways that improved on what was already there. They did so with tools and technologies that suffered from human limitations. But the result was architecture that is human and even sometimes beautiful. These places evolved in response to—and, were limited by—the people and communities that inhabited them, not the other way around. Can we find a way to make public policy that takes the same lesson to heart without retreating to a past that never actually existed?

This is where economic sociology comes in. I don’t go too much for economist bashing. I like economists. Some of my best friends of economists. The strength of their insights is undeniable. But there is no doubt that the quantitative turn in economics is the equivalent of the arrival of CAD technology in architecture. It has lead to an exceptionally technocratic era of policy analysis the goal of which is to rationalize and to engineer policy-making on a superhuman scale. Intellectually, it’s good stuff. But over-reliance on it, in combination with embracing a certain form of capitalism the last fifty years, has introduced a lot of the same problems that CAD technology introduced into architecture. We have extracted humans and history from the process of making policy and Trump (and Brexit, and Marine Le Pen) are a result.

Economic sociology, if it doesn’t get itself too distracted by fancy tools, has a contribution to make. Or more than a “contribution”, economic sociology could become the intellectual basis on which to build a new approach to thinking about public policy. One that reintroduces a focus on human interactions—with their faults and frailties, as well as their capacity for beauty and insight—as the central actor in the process by which strong societies—not just policies (i.e.,buildings) but societies—are built. It is not just a matter of understanding the behavioral psychology of people in response to the engineered policies in which they live. It is understanding how the interaction of human beings produces and evolves social institutions.

The irony of ironies is that Donald Trump—the guy who brought the idea of “look at me” architecture to its tackiest heights when he demolished the perfectly nice 1929 Art Deco Bonwit Teller building in order to build a minimalist brass-tinted-glass monument to value engineering—should be leading the populist policy “movement”. We can and should reject both his facile, anti-intellectual nostalgia and also the technocratic policy elitism of the second half of the 20th century. Economic sociology, or at least some version of it, seeks to understanding how institutional fabrics emerge and evolve. Yet we have not really figured out how to translate that knowledge to a wider audience. But, we need to (because if we don’t someone else will)

Yes we can.

the PROSPER Act, the price of college, and eroding public goodwill

The current Congress is decidedly cool toward colleges and the students attending them. The House version of the tax bill that just passed eliminates the deduction on student loan interest and taxes graduate student tuition waivers as income. Both House and Senate bills tax the largest college endowments.

Now we have the PROSPER Act, introduced on Friday. The 500-plus page bill does many things. It kills the Department of Education’s ability to keep aid from going to for-profit schools with very high debt-to-income ratios, or to forgive the loans of defrauded student borrowers . It loosens the rules that keep colleges from steering students into questionable loans in exchange for parties, perks, and other kickbacks.

And it changes the student loan program dramatically, ending subsidized direct loans and replacing them with a program (Federal ONE) that looks more like current unsubsidized loans. Borrowing limits go up for undergrads and down for some grads. The terms for income-based repayment get tougher, with higher monthly payments and no forgiveness after 20 years. Public Service Loan Forgiveness, particularly important to law schools, comes to an end. (See Robert Kelchen’s blog for some highlights and his tweetstorm for a blow-by-blow read of the bill.)

To be honest, this could be worse. Although I dislike many of the provisions, given the Republican higher ed agenda there’s nothing shocking or unexpectedly punitive, like the grad tuition tax was.

Still, between the tax bill and this one, Congress has taken some sharp jabs at nonprofit higher ed. This goes along with a dramatic downward turn in Republican opinion of colleges over the last two years.

Obviously, some of this is a culture war. Noah Smith highlights student protests and the politicization of the humanities and social sciences as the reason opinion has deteriorated. I think there are aspects of this that are problems, but the flames have mostly been fanned by those with a preexisting agenda. There just aren’t that many Reed Colleges out there.

I suspect colleges are also losing support, though, for another reason—one that is much less partisan. That is the cost of college.

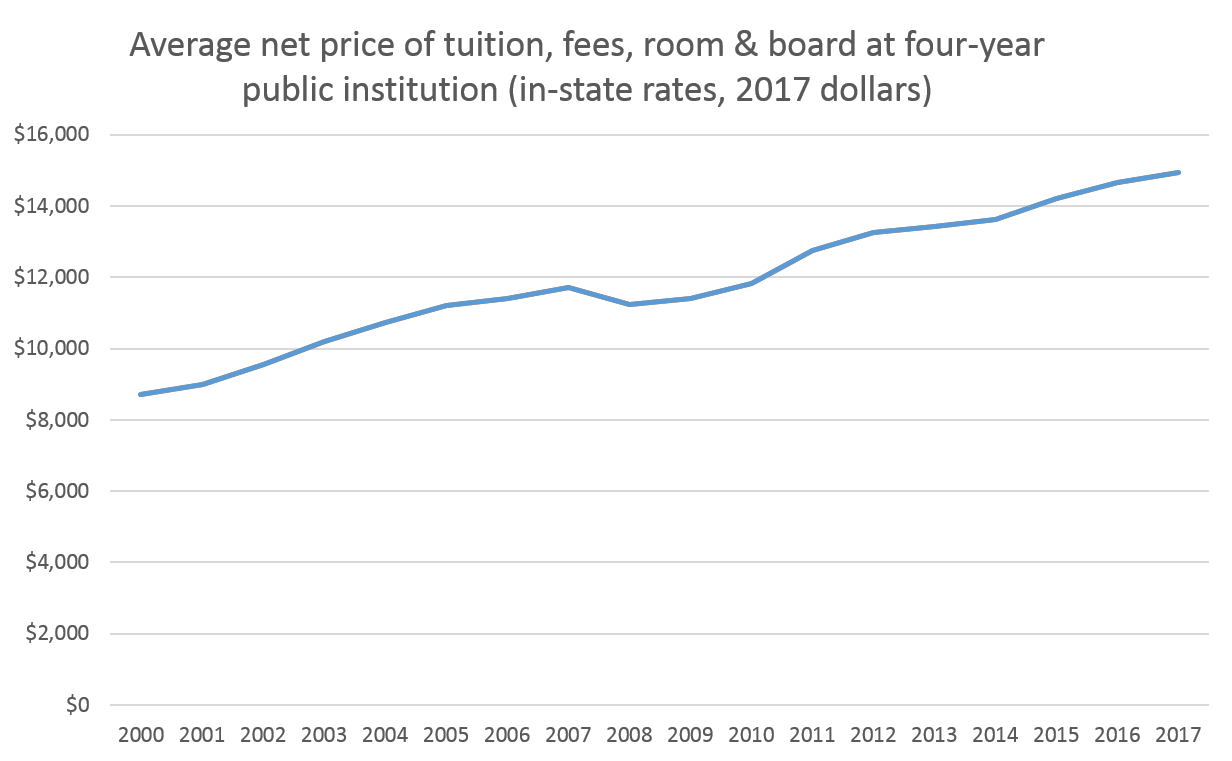

I think colleges have ignored just how much goodwill has been burned up by the rise in college costs. For the last couple of weeks, I’ve been buried in data about tuition rates, net prices, and student loans. Although intellectually I knew how much prices risen, it was still shocking to realize how different the world of higher ed was in 1980.

The entire cost of college was $7,000 a year. For everything. At a four-year school. At a time when the value of the maximum Pell Grant was over $5,000, and the median household income was not far off from today’s. Seriously, I can’t begin to imagine.

The change has been long and gradual—the metaphorical boiling of the frog. The big rise in private tuitions took place in the 90s, but it wasn’t until after 2000 that costs at publics (both sticker price and net price—the price paid after scholarships and grant aid) increased dramatically. Unsurprisingly, student borrowing increased dramatically along with it. The Obama administration reforms, which expanded Pell Grants and improved loan repayment terms, haven’t meant lower costs for students and their families.

What I’m positing is that the rising cost of college and the accompanying reliance on student loans have eroded goodwill toward colleges in difficult-to-measure ways. On the one hand, the big drop in public opinion clearly happened in last two years, and is clearly partisan. Democrats have slightly ticked up in their assessment of college at the same time.

What I’m positing is that the rising cost of college and the accompanying reliance on student loans have eroded goodwill toward colleges in difficult-to-measure ways. On the one hand, the big drop in public opinion clearly happened in last two years, and is clearly partisan. Democrats have slightly ticked up in their assessment of college at the same time.

But I suspect that even support among Democrats may be weaker than it appears, particularly when it comes to bread-and-butter issues, rather than culture-war issues. Only a small minority (22%) of people think college is affordable, and only 40% think it provides good value for the money. And this is the case despite the growing wage gap between college grads and high school grads. Sympathy for proposals that hit colleges financially—whether that means taxing endowments, taxing tuition waivers, or anything else that looks like it will force colleges to tighten their belts—is likely to be relatively high, even among those friendly to college as an institution.

This is likely worsened by the common pricing strategy that deemphasizes the importance of sticker price and focuses on net price. But the perception, as well as the reality, of affordability matters. Today, even community college tuition ($3500 a year, on average) feels like a burden.

The point isn’t whether college is “worth it” in terms of the long-run income payoff. In a purely economic sense there’s no question it is and will continue to be. But pushing the burden of cost onto individuals and families, rather than distributing it more broadly, makes it feel unbearable, and makes people think colleges are just in it for the money. (Which sometimes they are.) I’m always surprised that my SUNY students think the mission of the university is to make money off of them.

This perception means that students and their families and the larger public will be reluctant to support higher education, whether in the form of direct funding, more financial aid, or the preservation of weird but mission-critical perks, like not taxing tuition waivers.

The PROSPER Act, should it come to fruition, will provide another test for public institutions. Federal borrowing limits for undergraduates will rise by $2,000 a year, to $7,500 for freshmen, $8,500 for sophomores, and $9,500 for juniors and seniors. If public institutions immediately default to expecting students to take out the new maximum in federal loans each year, they will continue to erode goodwill even among those not invested in the culture wars.

The sad thing is, this is a self-reinforcing cycle. Colleges, especially public institutions, may feel like they have no choice but to allow tuition to climb, then try to make up the difference for the lowest-income students. But by adopting this strategy, they undermine their very claim to public support. Letting borrowing continue to climb may solve budget problems in the short run. In the long run, it’s shooting yourself in the foot.

brooke harrington has committed no crime

It is very unfortunate that an American sociologist working in Denmark, Brooke Harrington, has become entangled in immigration law. She is being charged with a criminal violation for giving lectures within Denmark. From Inside Higher Education:

Harrington’s research is controversial in that it deals with tax loopholes and offshore accounts of kind documented in the so-called Panama Papers. Yet that isn’t what Danish officials find problematic. Citing a series of lectures Harrington delivered — ironically — to members of the Danish Parliament, Danish tax authorities and a law class at the University of Copenhagen this year and last, they’ve charged her with working outside her university and therefore the parameters of her work permit.

Denmark has taken a relatively hard line against immigrants in recent years. The charges against Harrington are notable, however, in that she is an internationally recognized scholar, not a refugee or a low-skill worker — those who are more typically criticized in the country. Her case is also part of a bigger reported crackdown on foreign academics sharing their research in Denmark. Some 14 foreign researchers across Denmark’s eight public universities have been accused of violating their work permits on similar grounds, according to Politiken, a major newspaper.

Harrington faces $2,000 in fines and a much bigger problem: paying up simply to move on would mean admitting to a crime, with major repercussions for the rest of her career. Job applications and even travel visas often have a box asking whether one has ever been convicted of a crime, she said. There’s little room for nuance in answering a yes-or-no question, Harrington added, so “yes” applications typically get tossed in what she called “the round bin.”

Yes, I completely agree with Harrington’s supporters. She should not face criminal charges and they should immediately be dropped. I also urge that people should reconsider the strict work permit laws that exist in many countries. The state should not place these sort of regulations on work. A moral and just society does not impose arcane and arbitrary rules on how a person can earn a living, or where than can give paid lectures, and that applies to natives as well as migrants. If you feel that Professor Harrington has been treated unfairly, then you will easily understand how such strict rules curtail the freedom of millions around the world. Let’s support Professor Harrington and let’s support the right of people in general to live and work as they please.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine– It’s Awesome!

burning man’s worldwide, year-round influence

Burning Man 2017 has started its annual stint in the Nevada Black Rock Desert. If you’re like me, other commitments preclude joining this 60,000-plus gathering of persons. This live webcast shows some of what what we’re missing:

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCfVAyiqfH6gUq5FwzfoP2YA/live

Nevertheless, as I discuss in this invited fortune.com op-ed, Burning Man’s 10 principles have spread worldwide and year-round. You can find a Burning Man-inspired event or organization in your locality – check out the Burning Man regionals website for local events and the Burners without Borders website for humanitarian projects.

In my op-ed, I also discuss how Burning Man principles help shift people’s conceptions of what’s possible, including questioning everyday society’s practices and enhancing cohesion:

Burning Man doesn’t just manifest in visible settings—it has also expanded an inner, reflective world. In particular, the 10 Principles and Burning Man’s organizing practices—which include decision-making by consensus where people have a say in matters, rather than just deferring to hierarchical authority—enable people to raise questions about the society they wish to support. When confronted, for example, by turnkey camps at the Burning Man event where affluent people pay others to prepare their food, shelter, and entertainment, people can debate the contours and limits of the principle of self-reliance versus inclusion and community. These conversations encourage people to explore the nature of inequality, an issue that often is taken for granted or viewed as inevitable and immutable in conventional society. And people learn to deal with differences, such as asking: What do you do when people have conflicting interpretations of acceptable norms and practices?

For some, Burning Man will always be just a brief, fun party for meeting new and old friends; for others, it offers long-term transformative potential, both at the personal and societal levels. If and when Burning Man ceases to exist, its imprints are likely to endure throughout society, as its inspired offshoots continue to disseminate—and even reconfigure—the 10 Principles and organizing practices to local communities.

Read more of the op-ed here.

You can also see a list and links for my more scholarly writings about Burning Man here, and other scholars and writers’ publications here.

the post-racist society vs. donald j. trump

The central tragedy of America is the treatment of non-whites. From Indian wars, to slavery, to segregation, to internment camps, to deportations, to Guantanamo, American society has often betrayed its ideals. But the American story is also one of progress, not stagnation. From time to time, change does happen and it is good.

In my eye, one of the biggest transformations of American society was the de-legitimization of racism in the 1960s. Following a century of eugenics, Jim Crow and all other manner affront to human dignity, the Civil Rights movement managed to create one of the first modern societies where racism began to lose its legitimacy. Not only did African-Americans have their rights returned to them, but the culture around race started to shift as well. For the first time, it was no longer appropriate for public figures to openly disparage American blacks, and many other groups as well.

A while ago I called this new culture “the post-racist society.” Not because I believed race or racism were gone. But rather overt racism was illegitimate. You could be racist, but it had to be expressed in dog whistle politics. It was a submerged belief in the mainstream of American life. My belief in the post-racist society was initially shaken by the rise of Trump. For the first time in decades, a serious contender for the presidency was openly racist. My belief was shaken once again when he won.

But later, as I surveyed the evidence on how Trump rose to power, I realized that the death of post-racist society was greatly exaggerated. For example, Trump won on an electoral college fluke, not because a new nationalist majority propelled him to power. Another key piece evidence. Estimates of the GOP primary vote indicate that 55% of GOP voters preferred someone other than Trump (see the wiki for the basic data). Yes, there is a nationalist and racist strand within the the GOP and Trump essentially dominated that vote. But a causal reading of the GOP primary map shows that Cruz dominated the mountain states and split the Midwest. If you look at the vote tallies in many early states, Trump was winning with vote totals in the low 30% range. Not exactly a resounding victory.

After entering office, there has been no groundswell of nationalism or racism in this country. For example, approval ratings for Trump have been horrid and have sunk to historic lows. Obama’s approval barely dipped below 40% in the Gallup polls but Trump’s is already in the 30% range and has stayed there. Trump is not riding a giant groundswell of nationalism or expressing the outrage of a working class left behind. Rather, he’s an electoral accident propped up by the most recalcitrant elements of the Republican party.

Trump’s limited support in the American polity raises some interesting questions. If only 35% of people approve of Trump (mainly racists and loyal Republicans), then what is everyone else doing? As with many political things, a lot of people have sat out. But we are seeing other parts of the political system slowly respond to Trump.

Perhaps the most insightful example is Trump’s statement that he would ban transgendered individuals from the armed services. The response? The military essentially just ignored him. Just think about that. Another example – after Trump’s statements about the murder of a protester in Charlottesville, conservative GOP senators slowly criticized him and CEO’s started resigning from key committees. Then, of course, there is the disintegration of the GOP consensus in the Senate.

There is the usual resistance from the left that accompanies any Republican administration. I am sure that the events in Charlottesville will continue to mobilize people and surely Trump will offer the left more to be appalled at. His actions will likely sustain the groups behind the Women’s march and the march for science, as well as Obama era groups like Black Lives Matter. And of course, white supremacy groups have seen Trump’s election as a chance to come out of the wood works, which will trigger push back from the left.

One might attribute Republican softness and left resistance to Trumpian incompetence. Perhaps it wouldn’t exist with a more smooth, but equally racist, Republican politician. Maybe. But here’s another hypothesis – people in general aren’t ready to completely ready to ditch the post-Civil Rights cultural agenda. Segregation is not on the table and popular culture has not reverted to a stage where racial slurs are permissible. Black face is not on TV and will not be any time in the near future. We live in the world of Get Out, not Birth of a Nation.

So when white nationalist politicians, like Steve King or Trump, emerge in the GOP, they reflect the will of a sizable, yet limited, constituency. But that group is big enough to win elections in some rural areas, like Arizona or Iowa, and enough to push through a candidate in a split field. At the same time, it doesn’t indicate a slide back to the middle ages.

Does that mean that people should “just relax?” No. Rather, it means that it is possible to defend the post-Civil Rights social order. It is there and it is, haphazardly, pushing back. We need to do what we can to help it out. It’s hard, but it has to be done.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($4.44 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist (discount code: ROJAS – 30% off!!)/From Black Power/Party in the Street / Read Contexts Magazine – It’s Awesome!

the 80th percentile isn’t the problem

Okay, so I know three days is like a thousand years in internet time. But this Sunday Times op-ed, “Stop Pretending You’re Not Rich,” is still bugging me. The title is perfect guilty liberal upper-middle-class New-York-Times-reader clickbait. And sure enough, it was all over my social media feed.

But I think the piece gets things wrong in a particularly pernicious way.

The thrust of the op-ed, and presumably the book it’s promoting, is that upper-middle-class Americans—the top 20% by income—are the real problem, not the top 1%. They are capturing most of the income gains, hoarding opportunities, and they don’t even acknowledge their luck in being there.

A lot of the specific points, particularly about policies that benefit the moderately well-off at the expense of others, are easy to agree with. Exclusionary zoning is bad. 529 plans benefit the well-to-do almost entirely. The mortgage interest deduction is terrible policy.

But the real problem with the U.S. economic system isn’t the self-interested behavior of those in the top 20% of the income distribution. It’s that 1% of the population holds 40% of the wealth, and that GDP increases aren’t translating into higher incomes for most of the population.

The op-ed misdirects our attention away from these factors in multiple ways. First, it paints a misleading picture of this person in the top 20%.

Most obviously, it says that the average income of this group is $200,000, which I admit does sound pretty high. But using the average income to describe this fifth of the population is a problem, given the shape of the income distribution.

The median, which would be the 90th percentile, is $162,000. The 80th percentile is $117,000. (Here’s a quick calculator based on CPS data.) Very healthy, but not $200,000. The anecdotal illustration—the author’s friends who pay $30,000 a year for their kid’s high school tuition—also seems to point to someone with an income on the high end of this range.

Second, while the second decile is doing reasonably well, both its wealth and income are quite proportionate with its actual numbers. This paper is now slightly dated, but it does break out that decile—to show that in 2007 at least, it held 12% of total net worth, and made 14% of total income (see Table 2). You’d have to be pretty damn egalitarian to think that was unreasonably high for the next-to-top 10%.

Finally, yeah, the top 20% has seen more income gains than the rest. But the issue is less that they’re gradually getting better off, than that wages in general aren’t keeping up with either GDP growth or productivity. If you look at pre-tax income of the top 20%, exclusive of the top 1%, it’s increased by 65% since 1979 (see Table 1). Sounds like a lot—until you realize that real GDP per capita increased almost 80% during the same period.

So sure, the top 20% is unquestionably well-off, and indeed rich in global terms. And doubtless people in this group could show a little more self-awareness of their relative good fortune. And it would be nice if the mortgage interest deduction wasn’t the third rail of tax policy.

But the problem isn’t that the top 20% is doing reasonably well. It’s that the rest of the population should be doing that well, too. Ultimately, pointing a finger at the fortunate fifth is a sleight-of-hand that keeps our attention away from where it should be: on a much richer, more rarified group, and the broken system that allows it to capture the bulk of the gains that we as a society produce.

class and college

When awareness about the impact of socio-economic class was not as prevalent among the public, one exercise I did with my undergraduates at elite institutions was to ask them to identify their class background. Typically, students self-identified as being in the middle class, even when their families’ household incomes/net worth placed them in the upper class. The NYT recently published this article showing the composition of undergraduate students, unveiling the concentration and dispersion of wealth at various higher education institutions.

As a professor who now teaches at the university listed as #2 in economic mobility (second to Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology ), I can testify to the issues that make an uneven playing field among undergraduates. Unlike college students whose parents can “pink helicopter” on their behalf and cushion any challenges, undergraduates at CCNY are supporting their parents (if alive) and other family members, bearing the brunt of crushing challenges. (In a minority of cases, students’ parents might help out, say, with occasional childcare – but more likely, students are caring for sick family members or helping with younger siblings.)

To make the rent and cover other expenses in a high COL city, CCNY students work part-time and full-time, sometime with up to two jobs, in the low-wage retail sector. They do so while juggling a full load of classes because their financial aid will not cover taking fewer classes. For some students, these demands can create a vicious cycle of having to drop out of classes or earning low grades.

I always tell students to let me know of issues that might impact their academic performance. Over the years (and just this semester alone), students have described these challenges:

- long commutes of up to 2 hours

- landlord or housing problems

- homelessness

- repeated absences from class due to hospitalizations, illness/accidents, or doctor visits for prolonged health problems

- self-medicating because of fear about high health care costs for a treatable illness

- anxiety and depression

- childcare issues (CCNY recently closed its on-campus childcare facility for students), such as a sick child who cannot attend school or daycare that day

- difficulties navigating bureaucratic systems, particularly understaffed ones

- inflexible work schedules

These are the tip of the iceberg, as students don’t always share what is happening in their lives and instead, just disappear from class.

For me, such inequalities were graphically summed up by a thank you card sent by a graduating undergraduate. The writer penned the heartfelt wish that among other things (i.e., good health), that I always have a “full belly.” Reflecting this concern about access to food, with the help of NYPIRG, CCNY now has a food pantry available to students.

global resistance in the neoliberal university

…an international conference on Global Resistance in the Neoliberal University organized by the union will be held today and tomorrow, 3/3rd-4th at the PSC, 61 Broadway.Scholars, activists and students from Mexico, South Africa, Turkey, Greece, India and the US will lead discussions on perspectives, strategies and tactics of resisting the neoliberal offensive in general, and in the context of the university in particular.You can visit this site for a link to the conference program:Due to space constraints, conference registration is now closed. But we’re thrilled by the tremendous interest in the event! You can watch a livestream of the conference here: https://www.facebook.com/PSC.CUNY. If you follow us on our Facebook page, you will receive a notification reminding you to watch.We look forward to seeing some of you tonight and to discussing the conference with many of you in the near future.

supreme court game theory

Right now, Senate Democrats have a choice, they can vote to confirm Supreme Court nominee Neil Gorsuch or reject. This choice is complex:

- How desirable is this individual nominee?

- How desirable is it to filibuster this individual nominee, even if he is desirable?

- How desirable is it to punish Republicans for not holding a vote on Merrick Garland?

I think these issues are subtle and interdependent. For example, it is unclear whether Trump would nominate another Scalia type jurist, who is very conservative but does show some degree of independence. Thus, this may be “as good as it gets.”

However, voting in favor of Gorsuch, or simply not filibustering, raises a number of issues for Democrats. First, it essentially confirms a new norm in the Senate. If the President and Senate are from different parties, the Senate can deny the President the power to appoint any Supreme Court justices. This is a real shift. Technically, the power granted by the Constitution is “advise and consent,” not complete denial. Second, allowing the Gorsuch nomination to proceed without a major fight will probably inflame the base. The Democratic base could reasonably ask why Republicans are happy to filibuster and Democrats not so much.

My prediction is that Senate Democrats will allow Gorsuch to be nominated without much fuss because Democratic primary voters won’t punish them. The Democratic base seems to be very ineffective when it comes to punishing deviant behavior. Thus, the marginal Senate Democrat will probably focus more on general election voters in swing states.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($5 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

conspiracy theory, donald trump, and birtherism: a new article by joe digrazia

Joe DiGrazia, a recent IU PhD and post-doc at Dartmouth, has a really great article in Socious, the ASA’s new online open access journal. The article, The Social Determinants of Conspiratorial Ideation, investigates the rise in conspiratorial thinking on the Internet. He looks at state level Google searches for Obama birtherism and then compares to non political types of conspiracy theory, like Illuminati.

The findings? Not surprisingly, people search for conspiracy related terms in places with a great deal of social change, such as unemployment, changes in government, and demographic shift. This is especially important research given that Donald Trump first rose to political prominence as a birther. This research is indispensable for anyone trying to understand the forces that are shaping American politics today.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($5 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

the muslim registry is next, so it is time to prepare

Scatter Plot also has a post about political activism and the anti-refugee ban.

Only seven days into his presidency, Donald Trump has issued cruel executive orders aimed at immigrants and refugees. One recent executive order banned the re-entry of any individual who was a citizen of Iran, Yemen, Syria and other countries. The order was especially cruel in that it applies to travelers who had already secured visas, green cards, and other paper work. Observers noted that the order applied to newborn infants, the elderly, and the disabled, none of whom present risk.

In response, lawsuits were filed and protests erupted. Thankfully, at least two federal court judges believed that the executive order was likely invalid and ordered a stay. However, this is a short term victory. It will not be hard for the Trump administration to rewrite executive orders and propose legislation that comply with American law. This is because courts time and time again have agreed that people do not have the freedom of movement.

As time passes, the Trump White House will learn how to write policy in ways that pass judicial review and that are approved by Congress. This is deeply problematic on two levels. First, restrictions on migrations are irrational and cruel, no matter who is president. But also, the successful imposition of anti-immigration policy will embolden the White House to follow through on one of Trump’s most repulsive proposals, a religious registry.

What do to? I think the strategy is obvious. Simply, resist these anti-immigration proposals now so that future proposals are harder pass. How? There are simple ways: simply say to your friends and family that immigration is ok; call your local representatives; donate to groups that litigate on behalf of immigrants; and, for the brave, their will be plenty of chances of non-violent civil disobedience.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($5 – cheap!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

the polls did better than you expected in the 2016 election, but not state polls, they sucked

Remember when everybody said that the polls completely got the 2016 presidential election wrong? Now we have final numbers on the popular vote count, and guess what? The national polls were on target:

- In the Real Clear Politics rolling average, the final estimate was HRC up by 3.3%. In the final popular vote count, the Cook Report found that the final difference was 2.1%. Being 1.2% off on the margin is pretty flipping good.

- In terms of the percent per candidate, the polls did worse because people over reported support for 3rd parties. Stein and Johnson together got 3% more in the polls than the results. This is evidence for the “parking lot theory of third parties.”

However, the state polls sucked. Not too hard, but they did suck a little bit, except Wisconsin and Minnesota, which totally sucked:

- Wisconsin – off by over 7%.

- Michigan – off by 3.4%

- Ohio – off by 4.6%

- Pennsylvania – off by 2.6%, which is not bad. HRC losing Pennsylvania was definitely within the margin of error here.

- Minnesota – off by 4.7% (My average, 6.2% vs. 1.5% final)

This is consistent with conventional wisdom about state polls, which is that they are less reliable because it is hard to pinpoint people in states, hard to identify likely voters, and have smaller electorates that can fluctuate (e.g., voter registration laws or bad weather).

Still, in retrospect, looking at state polls did suggest that a popular vote/electoral vote split was possible. A Trump victory was within the margin of error of the polling average in a number of states such as New Hampshire and Pennsylvania. This observation about state polls is also consistent with the finding that the HRC lead was due to urban centers.

Bottom line: The conventional social science about polls held up. National polls do decently, states polls a bit worse and in some cases badly. However, they was plenty of evidence that Trump might get an electoral college victory, but you had to really read the state polls carefully.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

the core ideology of the gop: a response to seth masket

Over at Pacific Standard, Seth Masket expresses surprise at the fact that many in the Republican party have abandoned traditional GOP policy goals and ideological beliefs:

Most recently, this has been apparent in Trump’s responses to reports by American intelligence agencies that Russia and WikiLeaks hacked Democratic National Committee servers and worked to undermine Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign… Most recently, this has been apparent in Trump’s responses to reports by American intelligence agencies that Russia and WikiLeaks hacked Democratic National Committee servers and worked to undermine Hillary Clinton’s presidential campaign.

And it doesn’t stop with the GOP’s new Russophilia:

Another core tenet of modern Republicanism, of course, is free-market capitalism. The best economic system, the party maintains, is one in which businesses can operate with minimal regulation and thus produce wealth and innovation that benefit everyone. Trump’s approach has literally been the opposite of that. To use the tax code and other tools to selectively bully and punish companies that exhibit undesirable but legal behavior, such as building plants in other countries, is many things, but it’s not free-market capitalism. But many Republican leaders have nonetheless enthusiastically backed Trump’s approach.

I have a different view. My opinion is that GOP talking points are cheap talk and did not express true ideological commitment. For example, Republicans talk free trade, but they feel free to restrict labor through migration restrictions, they were always willing to give breaks to specific firms, and hand out subsidies to specific groups (remember the faith based initiatives?). A strict libertarian approach to trade in the GOP has really been a minority view. In other words, “free trade” is fun to say but in practice, they don’t follow it. It’s yet another example of “libertarian chic” among conservatives.

So what’s my theory? Like all parties, the GOP is a pragmatic coalition. Ideology is secondary in most cases. It’s about getting a sufficiently large block of people together so you can win elections. If you believe this theory of political parties, ideology is really not that important and, in most cases, it can be dropped at any time. In American history, for example, the Democrats and Republican parties switched positions on Black rights as part of an attempt to win the South.

This theory – that ideology is only as good as its ability to maintain a coalition – best explains the GOP policy points that Trump has rigidly stuck to: anti-immigration and abortion. And it makes sense, the two most steadfast groups in the GOP are social conservatives/evangelicals and working class whites in the South and Midwest. These groups don’t care much about foreign relations or free trade. What Trump has shown is that populism will melt away every thing except your most cherished beliefs.

50+ chapters of grad skool advice goodness: Grad Skool Rulz ($2!!!!)/Theory for the Working Sociologist/From Black Power/Party in the Street

thinking carefully about the dangers of a trump administration

There have been a few responses to Donald Trump’s surprise victory last month. On the left, many immediately jump to the conclusion that he’s a new sort of Hitler. On the right, there’s been a sort of sigh of relief. The dreaded Clinton machine is now banished. I am not happy with Trump, but on the other hand I was not happy with Obama either.

For example, on a lot of issues, Trump will simply continue the policies of Obama, and Bush, that I thought were bad. The main example is immigration. Obama has now deported more people than any other president. Another example is war and conflict. The Obama administration has been involved in Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, Yemen, and Syria. Even though Trump said that Iraq was a mistake, he’s appointing a lot of hawks. I expect Trump and Obama to have similar policies.

At the same time, I do not pretend that Trump and Obama are identical or that Trump is a typical Republican. Trump acts like an authoritarian. He demonizes out groups, he threatens harm, and openly flouts norms concerning conflicts of interest. My sense is that a Trump administration will combine two things: Latin American style populism and 1910/1920s style social relations. The first claim is straight forward: the Tea Party, and Trump, are populists and admittedly so.